Up to 200 Cambodian American deportees expected in 2018 as US repatriates more immigrants

Cambodian Americans who have committed a crime face possible deportation from the country they now call home.

Father-of-five Jimmy Heim had spent nearly 40 years in the United States when he was deported to Cambodia, a place he barely knew. He is part of the growing community of Cambodian-American returnees, whose number is expected to rise by up to 200 this year. (Photo: Pichayada Promchertchoo)

PHNOM PENH: Loneliness can be frightening.

It is how Jimmy Heim felt in August 2016 when he was flying from the United States to a place he barely knew. Every second took him further away from his entire existence as a US resident. Everything he had built up over nearly 40 years - his wife and five children, his job, his house and friends - were ripped away the moment he was convicted of a crime and barred forever from the country he calls home.

“I wasn’t shackled. But being alone was even more frightening, not able to share or express my thoughts or emotion with another member,” Heim told Channel NewsAsia as he recounted the day he left the US for good.

Escorted by two US immigration officers, Heim was bound for a life in exile in his estranged homeland of Cambodia, thousands of kilometres away. He did not have a clear plan of how to spend the rest of his life or know any immediate family he could turn to for support. His Khmer language skills were rusty to the point of uselessness. All he had was US$1,000, some clothes and an unsettling fear that he would somehow do something wrong and get into trouble again.

"Someone advised me not to bring more than US$1,000 because I'd be interrogated about cash. So I had US$1,000 on me. Before I was escorted out of the plane, I asked to use the restroom where I rolled my cash and hid it inside me internally, afraid that I'd get strip-searched."

Heim is just one of hundreds of Cambodian green-card holders who violated US law and faced the prospect of deportation. He was convicted of an armed robbery, burglaries and assault with a firearm and served time in prison.

When he touched down in Phnom Penh in 2016, he became part of the growing community of Cambodian deportees. More than 600 of them have been expelled from the US under its immigration law, which enables the removal of legal permanent residents convicted of an aggravated felony.

On Apr 5, 43 of them touched down in the capital. They were the latest and largest group of deportees received by the Cambodian immigration since 2002, when Phnom Penh and Washington signed a memorandum of understanding to accept the return of their nationals.

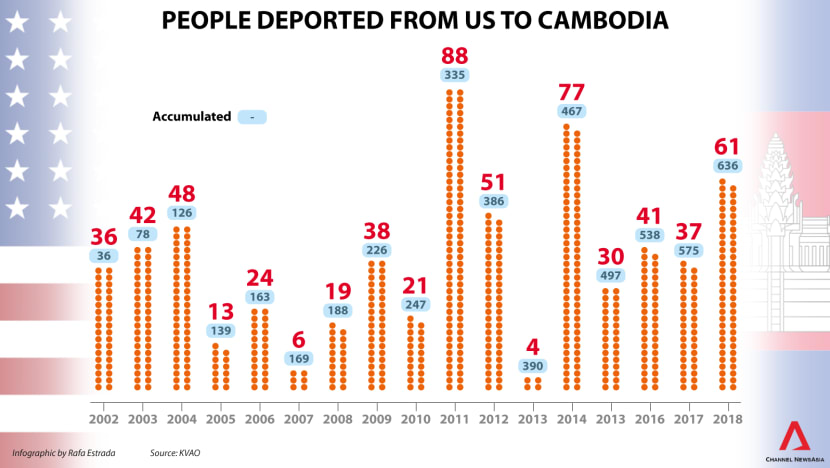

Based on data from the Khmer Vulnerability Aid Organization (KVAO), a leading Cambodia-based humanitarian group supporting deported Cambodian Americans, their numbers are on the rise. The arrivals went up from 36 in 2002 to 88 in 2011. Although the number dropped to 37 last year, it was only because Cambodia refused to accept its deported nationals.

In response, the US government under President Donald Trump imposed visa sanctions on Cambodian foreign ministry officials and their families in September. The move successfully pressured Cambodia to resume the repatriation process. With the programme back on track, 61 Cambodian Americans have already been deported since the start of 2018. More than 100 others are also expected to be pushed out of the US by the end of this year.

“There are still a lot of Cambodians who are serving their sentences in the US. From what I know, there are about 1,000-2,000 of them,” said Cambodian interior ministry spokesman Khieu Sopheak.

We can’t abandon them since they’re Cambodian. But honestly, we don’t want to take them back. We want them to live there.

‘UNJUST, IMMORAL, UNETHICAL’

Since 2002, the US government has deported 636 Cambodian nationals. Many of them are children of refugees who fled Cambodia during the oppressive rule of the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s, when almost a quarter of the population was wiped out in a four-year genocide.

Heim was five years old when his family escaped the regime’s atrocities. Many other children were born in refugee camps and resettled in the US, unaware of the importance of acquiring US citizenship for which they were eligible. A great number of them did not know they could be deported and had never set foot in Cambodia until they were repatriated decades later.

“These are Americans of Cambodian heritage," said Bill Herod from KVAO.

Culturally, they’re Americans. They eat American food, listen to American music, tell American jokes and watch American movies. They all speak Khmer – some not so well and others with the West Coast accent – but they’re Americans.

Adjusting to a new life is tough for many deportees. What connects them most to the country is perhaps their Cambodian nationality and, for the likes of Heim, limited Khmer vocabulary.

A great number of the deportees feel ashamed and try to hide from their past, fearing they would be discriminated against if people found out who they really are.

Heim kept his past secret when he first arrived in Phnom Penh. He rarely left his house or mingled with the locals and often felt the need to repeat the lie commonly told by deportees, that he was only visiting and would go back in a year or two, knowing that day would never come.

I had to play that role because if they knew I'm one of the rejects, they wouldn't even want to talk to me and might mistreat me, you know, or, in some kind of way, I wouldn't get that opportunity.

"All locals looked at me strangely because I’m tattooed and bald," he added. "I was alone."

This aspect of the programme has prompted some commentators to criticise Washington for what seems like double punishment against its legal permanent residents who have already served prison sentences in the US.

Several ex-convicts were deported for crimes they committed as minors, according to Herod. Numerous cases, he said, involve trivial, non-violent misdemeanours considered felonies under US immigration law. Some deportees had been released for years and already resumed their normal lives – with a family, house and stable job – when they were forced to leave everything behind.

"We have an older gentleman in his 60s who was released from a long sentence and deported the next day. A college graduate in social work, married with two children, had some marijuana and that was it - deportation for life," Herod said.

Besides, many deportees were caring for elderly parents who escaped the Khmer Rouge. But with their criminal record, their chance of going back to the US, even for a short family visit, is seen as likely impossible. While some of them are only banned for a few years, applying for a non-immigrant visa after being deported for a criminal offence is usually pointless.

"It’s forever. It’s lifetime," Herod said, adding he has come across hundreds of heart-breaking stories at KVAO.

They come and say ‘My mother is dying. Can I get a special permit to go back, to be with her at the end?’ No you can’t.

'ALL WE NEED IS THAT CHANCE'

Formerly known as the Returnee Integration Support Centre, KVAO has been assisting deported Cambodian Americans since the first batch arrived in 2002. It provides a wide range of support including documentation, housing, employment and, in some cases, life-time care.

Many deportees have successfully integrated into Cambodian society, where they have raised families and secured jobs in various sectors, from IT to education, hospitality, tourism, media and advertising.

Based on KVAO’s data, more than 100 deportees are teaching in schools. Several of them are successful tour operators, business entrepreneurs and managers at various firms. A few NGOs and civic groups have also been founded by the community to tackle drug-related problems and other social issues.

One of them is 1Love Cambodia, a local support group for returnees that Heim is working for. Its centre in Phnom Penh is open to any deportees wishing to hang out together or seeking support as they start a new life. Its staff also works with new comers and the existing community to lend a hand whenever it is needed. They expect to offer language classes and orientation programmes in the near future.

“I want everybody who has to be here to have a life. You get a fresh start. You don’t have to watch over your back. You don’t have a warrant. You can start all over," he said.

“Everything is possible here. Anything. All we need is that chance.”