commentary Commentary

Commentary: India had managed to curb COVID-19. That has now changed

India hit a five-month high for cases this week, but it will need to revisit the factors that gave it a breather for 10 weeks earlier this year, say NUS’ Dr Karthik Nachiappan and Dr Diego Maiorano.

A man reacts as he receives a dose of COVISHIELD, a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine manufactured by Serum Institute of India, at an auditorium, which has been converted into a temporary vaccination centre, in Ahmedabad, India, March 26, 2021. REUTERS/Amit Dave

SINGAPORE: In February, COVID-19 was in retreat in India. Infections dropped precipitously from 100,000 cases per day in September 2020 to as low as 8,635 on Feb 1.

From Dec 29 to Mar 12 – for more than 10 weeks - India maintained a weekly average of about 20,000 cases, prompting some to suggest the country had hit herd immunity.

Unfortunately, since Mar 10, daily cases have been on the rise surpassing the 20,000 level, hitting more than 68,000 on Monday (Mar 29) – a five-month high for India. The weekly average now stands at more than 53,000.

READ: Commentary: COVID-19 will cast long shadows of social repercussions

The drop in cases initially - given India’s size, density, difficulty to physically distance, at least in urban areas, and patchy policies - has mystified scientists, scholars, and public health experts alike.

Especially when the government had eased restrictions and reopened the economy during this period.

Why did cases drop and why have they since risen?

We don’t have a definitive answer to the puzzle. Rather, several factors could have contributed to the dip, which resulted in record low cases and the rise we are seeing now.

THE DIP

India has certain advantages that appear to have worked in its favour with COVID-19 cases and fatalities.

For one, demographics have been a boon. Only 6.18 per cent of the Indian population is over 65, which helped reduce mortality rates.

India now records around 240 deaths per day from COVID-19 but for much of February, this number had dropped below 100.

Even now, India’s pandemic-caused deaths – at 0.19 per 1 million of the population – is lower than the US (2.90) and UK (0.95).

For instance, in Italy and Japan where 22.7 percent and 28 per cent, respectively, of the population are in the above 65 cohort, the fatality rate is higher.

On per 1 million of the population, Japan’s COVID-19 death rate is 0.25 whereas Italy’s is 7.07.

Second, India’s geographic makeup could have blunted COVID-19’s potency.

Nearly 70 per cent of the population survives on agriculture, living in rural areas, which affects transmission patterns, possibly giving authorities time to arrest outbreaks before they spread.

The group most devastated by the pandemic is possibly the urban poor, who lack the means and mechanisms to deal with capricious lockdowns, onerous travel restrictions, and other constraints.

READ: Commentary: Without a vaccine, how can pregnant mothers protect themselves against COVID-19?

READ: Commentary: US at inflection point in beating COVID-19

India’s internal migrants have suffered from the initial lockdown in March 2020, which gave them four hours of notice, after which they found themselves without a job, shelter or social support.

Mass migration ensued towards the countryside – tens of millions left India’s cities in April and May 2020 – during which many faced severe, often fatal, destitution.

Other public health measures could have made a difference in lowering infections.

First, testing and identification, the first lines of defence, improved. India scaled up its laboratory capacity as conditions on the ground changed.

Early on, Indian officials widely relied on the PCR test, the gold standard of testing, before switching to rapid antigen tests (RAT), which are less reliable but yield results quicker.

Infectious disease experts generally agree that countries should use both methods, mixing the less sensitive RAT with the more accurate PCR. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Ministry of Health (MOHFW) have also enhanced testing efficiency by developing supplies like swabs for domestic use.

Better public and private testing also reduced the time in getting test results back, which affected isolation and quarantine strategies.

Contact tracing and concomitant isolation measures allowed the government to understand how infections’ spread and manage it thereafter.

New Delhi also worked with the private sector to design and mandate a contact tracing app, Aarogya Setu, which uses GPS and Bluetooth signals to alert users of COVID-19 cases around them.

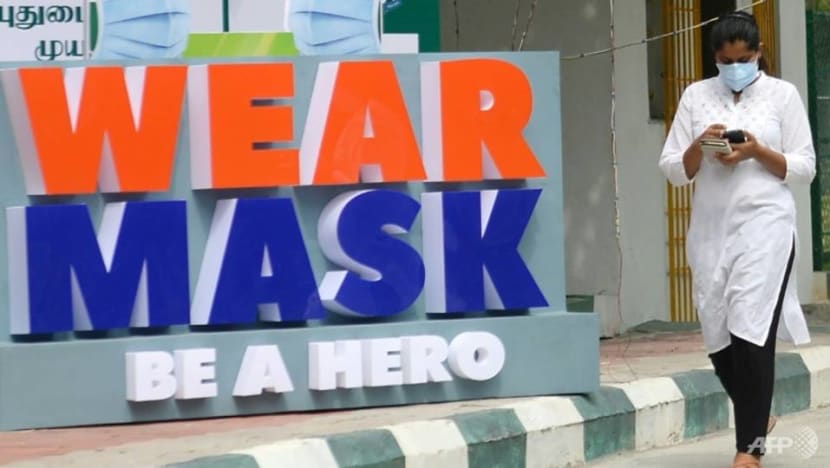

The Indian public also responded to combat the pandemic. Mask use increased. Indian health officials claim that India’s success comes down to unquestioned mask acceptance and use.

Authorities from the prime minister down urged citizens to use masks, unlike other countries where the issue entangled with questions of freedom and autonomy.

READ: Commentary: With millions vaccinated, Israel is test case for life after COVID-19

Police officials in cities like Delhi issued penalties to enforce mask use.

Rising mask demand was met by local manufacturers, which doubled their production capacity to nearly 4 billion.

Production reached a stage in late 2020 where the government could lift a ban on the export of N-95 masks to help manufacturers clear excess inventory and resume production.

THE SPIKE

Given these measures, how can we explain the recent spike in infections?

Cases are rising across the country with Maharashtra leading the way. Some of the measures indicated above could have flagged, especially mask use and testing as complacency among the public and officials on the ground crept in.

Election campaigns, especially in populous states like Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, could have triggered the uptick.

Indeed, infections are rising in both states. Furthermore, months-long, large scale protests by farmers at the outskirts of Delhi and across Punjab and Haryana could have also contributed to rising infections.

Finally, given India’s size, it is possible new COVID-19 variants could have accelerated the recent spread, though evidence here appears inconclusive.

It is likely that complacency and a sense of optimism around potential herd immunity in certain areas could have unleashed the current surge.

Recent serological tests indicate that this could be the case.

READ: Commentary: Is Southeast Asia on track for post-pandemic recovery?

In major cities, especially in slums, populations with COVID-19 antibodies were estimated to be between 20 per cent and 50 per cent in August to September last year, which suggests some form of immunity.

In a recent study covering rural and urban Karnataka, with a population of about 64 million, researchers estimated that the infection rate was 47 per cent.

While it is unclear what proportion of the population needs to be infected to acquire herd immunity, some researchers think it could be below 50 per cent.

Decreasing case loads and public pronouncements of herd immunity could have lulled Indian citizens into believing that the worst has passed. Mask use appears to have waned.

Herd immunity or not, New Delhi must augment testing processes, identify cases, enforce mask orders, and other relevant distancing measures while ensuring enough data flows up to monitor the transmission of the virus.

Monitoring the spread of new variants – that some scientists claim is behind the recent surge in cases – should be made a priority by enhancing ongoing genome sequencing efforts.

READ: Commentary: What’s behind India’s generous vaccine diplomacy?

READ: Commentary: Chinese vaccine diplomacy in Southeast Asia seeds goodwill but has limited strategic gains

The arrival and administration of vaccines could have also, ironically, spiked cases. Vaccines breed complacency.

India has an important advantage over other developing countries: A sizable proportion of the world’s vaccines are manufactured within its borders.

Vaccines are now available relatively quickly in big cities, where infections are picking up. New Delhi has to redouble vaccination efforts across urban and rural areas.

More than 40 million Indian citizens have received, at least, one dose of a coronavirus vaccine. This pace must quicken to blunt the resurgence.

The government hopefully did not make a fatal mistake when it approved the locally produced Covaxin before the results of phase-3 trials were available.

This blindspot could have dented public trust in Delhi’s vaccination’s campaign, including among medical personnel. Fortunately, Covaxin turned out to be safe and effective and India now has several vaccines approved.

The success or failure of India’s pandemic response in 2021 will be measured by whether the Indian government can rekindle the successes wrought by various policies near the end of 2020 and how effective the ongoing vaccination campaign is.

Dr Karthik Nachiappan is Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore. He is the author of Does India Negotiate? published by Oxford University Press in October 2019. Dr Diego Maiorano is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) at the National University of Singapore.