Malaysia's indigenous tribes fight for ancestral land and rights in a modern world

Mr Seu Med lives with his family in this hut at the Muadzam Shah landfill in Rompin district, Pahang. (Photo: Vincent Tan)

ROMPIN, Pahang: It was a Saturday afternoon, and garbage compactor trucks were rolling into the 4.9ha solid waste landfill at Muadzam Shah in Pahang’s Rompin district to dump their contents.

Situated 10 to 15 minutes’ drive from the main town, this landfill is the main source of income for Mr Seu Med, 28, and his extended family. They eke out a living by picking recyclables to sell to scrap dealers who drop by weekly from Kuantan, or Segamat in Johor.

Puffing on a cigarette, Mr Seu told CNA: “Maybe each round, we earn about RM80 (US$19) to RM100. We pick bottles, tins and other metal items to sell to the tauke besi buruk (scrap dealer).”

Mr Seu is a Jakun, one of the 18 ethnic groups recognised as Orang Asli (indigenous people) in Peninsular Malaysia by the federal government.

The settlement he is currently staying has nine kelamin - the term for nuclear family in some Aslian languages - and two or three more further in.

The traditionally nomadic villagers moved here about two years back, and there is no water supply in their settlement.

Every day, they walk or ride motorcycles to nearby ponds to bathe and fill up their five-litre mineral water bottles. A one-way trip can take 10 minutes by motorcycle or more than 30 minutes by foot.

The plight of the Orang Asli communities has been in the spotlight lately, following a spate of 15 mystery deaths and numerous hospitalisations suffered by the Bateq tribe in Kuala Koh, Kelantan.

Forced religious conversion, displacement from their traditional forests, lack of basic amenities and racial discrimination are among the problems faced by this small segment of Malaysians.

Prior to Kuala Koh, they barely registered in mainstream consciousness, if at all.

At worst, the names for ethnic groups, such as Jakun and Sakai, have been turned into derogatory terms in daily conversation denoting a “bumpkin” or “unsophisticated person”.

The government has made it a point to empower the Orang Asli through the introduction of a variety of assistance programmes, such as entrepreneurship development and further education schemes for scholars.

Tok batins (the spiritual and communal leaders) also receive a stipend from the government.

However, there is much to be done for the native communities.

Activists and non-governmental organisations (NGO) are frustrated over what they have perceived as injustices against the Orang Asli.

The federal agency tasked with overseeing the indigenous affairs, the Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA), has promised to safeguard the Orang Asli rights.

For a start, it will map the villages and apply for Orang Asli lands to be gazetted as heritage land, so to guarantee their livelihood and places of residence.

READ: Orang Asli village in Kelantan afflicted with measles outbreak: Malaysian health minister

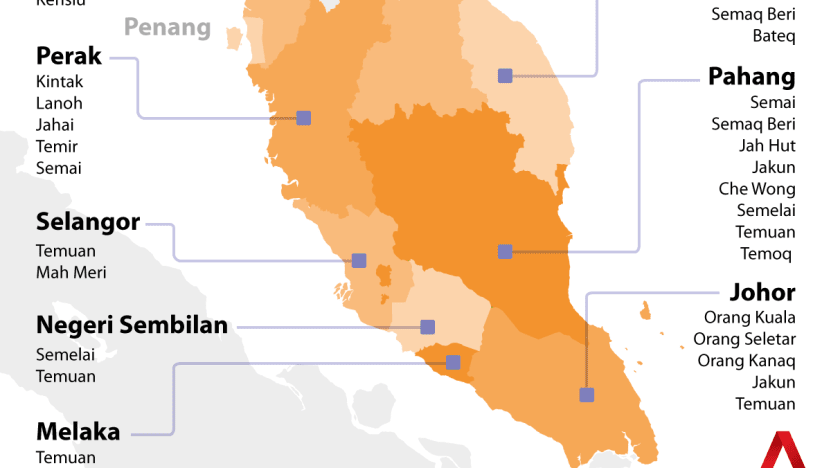

DIVERSE ORANG ASLI POPULATION IN WEST MALAYSIA

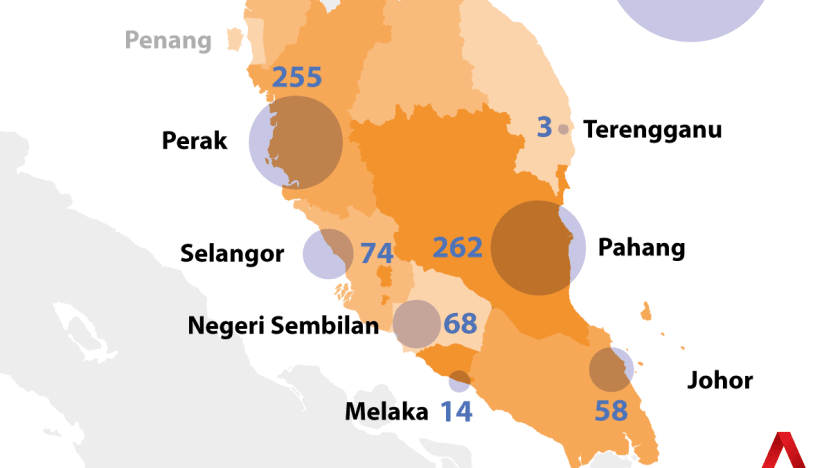

According to official data, there are 853 Orang Asli villages scattered throughout nine out of 11 states in the peninsula.

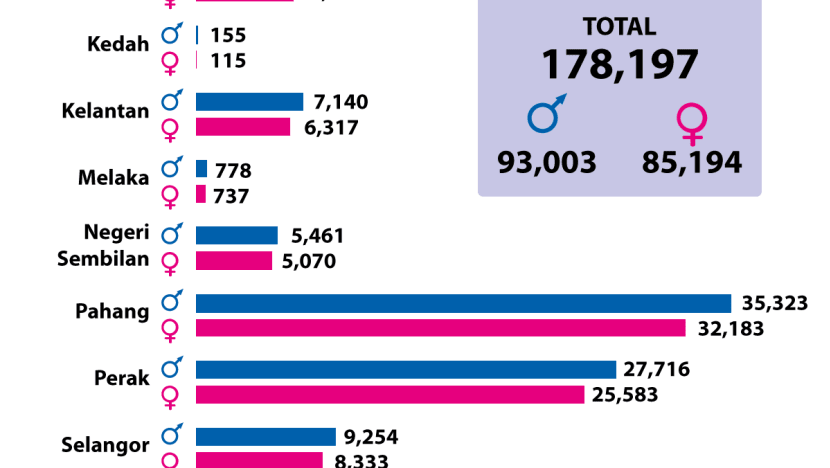

The total indigenous population count stood at 178,197, based on the 2010 Orang Asli Census.

Despite accounting for only 0.5 per cent of the country’s 31.6 million population, the Orang Asli population is diverse.

They are officially divided into three major groups - the Negrito or Semang, Senoi and Proto-Malays - and subdivided into a further 18 linguistic groups.

A 19th, the Temoq, were absorbed in the 2010 census into a larger neighbouring linguistic group.

The 2010 official figures were a marked increase compared to some 50,000 recorded back at the start of independence.

Researcher and Orang Asli advocate Dr Colin Nicholas attributed this seeming boom to two factors - better census-taking methods and better healthcare access.

“Previously there was just estimates. The census taker wouldn’t go into the villages or the interior, they would just get the numbers from a villager coming out of the interior.

“Now there’s better transport and access, so the actual numbers are more than initially believed at first,” said Dr Colin, who founded the Centre for Orang Asli Concerns to champion Orang Asli indigenous rights.

Improvements in healthcare access has also boosted infant and maternal survivability among Orang Asli.

Dr Colin noted that previously, three out of five mothers who died in childbirth were Orang Asli mothers, due to reasons such as poor healthcare access and lack of communication.

One solution to this was to bring in near-term Orang Asli women to local district hospitals and look after them until delivery, ensuring both the mother and infant’s safety as well as proper documentation.

“But at a social cost, because the mother is separated from her family in the interior or the village, leading to a breakdown, both mentally and socially, to the Orang Asli family unit. But the statistics improved,” Dr Colin said.

On July 9, a group of Orang Asli women from the state of Perak also alleged that Health Ministry officers had doled out birth control injections, insisting they take contraceptives despite resistance on their part.

Some say these examples reflect how little the rest of Malaysians understand Orang Asli communities, their customs, culture and way of life. At times, they might be too eager to encourage the native people to adapt to modern life.

READ: In a first, Malaysia sues Kelantan over Orang Asli land rights

WATER WOES

Basic infrastructure, like access to potable water, remains out of reach for some Orang Asli villages.

Nine households at Kampung Bukit Biru, a former dumpsite near the Muadzam Shah landfill, rely on two ponds and water pipes at the main road for their daily needs.

"This pond water is from water flowing downhill. Sometimes it gets discoloured.

“Usually we get our drinking water from the water pipes running by the side of the road. If the pipes are dry as well, then we’ll dig wells for drinking water,” Mr Saamah Gong, 43, said.

Global Peace Foundation, an NGO, supplied water filters to the villagers.

“We have cirit-birit (diarrhoea) from time to time, but if we use the filters, we don’t get sick very often,” Mr Saamah said.

To support their livelihood, the Kampung Bukit Biru villagers turn to the forest, foraging for produce to sell to traders, such as bertam palm fronds. These are useful as fishing rods, blowpipe darts, thatching, or stakes for planting creeping vegetables.

Gathered, dried and then tied into bundles of 500, Mr Saamah sells them for RM25 a bundle.

Elsewhere in Kampung Batu Putih in the same district, Global Peace volunteers were putting in place a solar-powered water delivery system.

“We’ve built water towers located throughout the village so that they don’t have to travel everyday, and also provided portable water filters to eliminate 99.999 per cent of viruses and foreign objects in the water,” explained Dr Teh Su Thye, the CEO for Global Peace’s Malaysian chapter.

For Mdm Juriah Genges, 30, a mother of three children, the water towers and filters are a godsend.

“We’ve been living here for two years, we usually walk to a pond about 15 to 30 minutes away,” Mdm Juriah said, cradling her one-year-old baby girl.

Many villagers find work where they can, such as in Muadzam Shah as labourers, or go into the forest to collect bamboo or tualang tree honey, or hunt for bullfrogs, said local tok batin Ayeng Jara, 60.

FOREST LANDS UNDER THREAT

Other than those living in urban settings, many Orang Asli communities forage in the forests and practise shifting agriculture, where the land is cleared and cultivated for a few years, then the community moves on and leaves the former agriculture land to regenerate.

The forests also provide food in the form of hunted animals, of which the Orang Asli never take more than they need for fear of a curse befalling them.

Orang Asli never refer to the animals by their actual name. The Temiars in Kampung Tasik Asal Cunex, Perak, for instance, call elephants “orang besar” (big person) and tigers “Maybank”, due to the banking group’s logo.

By far, the biggest threat to the Orang Asli traditional way of life appears to be the encroachment of their forests.

READ: Orang Asli land under threat in Pahang as Musang King plantations grow

Conflict between the Temiars of Kampung Tasik Asal Cunex Hulu Air Denkal and loggers backed by the Perak government reached a flashpoint earlier this year, when state officers, accompanied by the police’s paramilitary General Operations Force, swarmed and removed the blockade erected by the Cunex villagers.

More recently, another conflict point also emerged between villagers and loggers in Kampung Sungai Papan, Perak, resulting in three Temiars being handcuffed by the Perak police and brought to the nearby town of Grik to have their statements taken on Jul 20. The police later clarified that the men were not arrested.

For the Cunex villagers, the fight to protect their lands holds religious significance as well, as their traditional creation myth holds that the waterfall was a stopping point for their creator deity Aleuj and the Sun during the pair’s journey from east to west.

Cunex villager Mr Azahar, who goes by one name, said he participated in the blockades several times and recorded the loggers’ actions towards the villagers.

“In the second last blockade, I was also down there recording the demolition. They tried to grab my phone but I escaped and hid behind trees until the coast was clear, then I quickly rode my motorcycle to a point where there’s phone reception to send the recordings to the NGOs,” the 25-year-old recounted.

INVOLUNTARY CONVERSION

Traditionally, Orang Asli were animists, but more and more members of the community embrace monotheism to become either Muslim or Christian, while some have also embraced other religions like Buddhism and Taoism due to intermarriage.

However, the conversion is sometimes not entirely out of their own free will.

In a memorandum submitted to JAKOA’s director-general Dr Juli Edo in July, Temiars from Perak complained that many Temiars had been registered as Muslims in their identification cards, despite not having converted at any point.

Just after the Kuala Koh deaths broke out, the Kelantan state Islamic Religious Council announced its plan to fully convert all Orang Asli within the state in the next 30 years, drawing a rebuke from Dr Juli to let the Orang Asli’s traditions be.

According to Dr Colin and lawyer-activist Siti Zabedah Kasim, issues such as involuntary conversion have long been an issue for the Orang Asli.

“The issue with this forced conversions was that until Christians began proselytising to the Orang Asli - the last of the ‘poor lost souls’ - the Malays had never paid the Orang Asli any attention,” said Dr Colin.

“Christian proselytisation was so active that in 1983, there was a federal government policy to convert all Orang Asli to Muslims,” Dr Colin said, adding that converts were promised cash, new clothes, housing and priority for development.

The memorandum by the Perak Temiars also called for Christian proselytisers to leave the Orang Asli villages alone.

Meanwhile, in a roundtable organised by two local higher education institutions on Orang Asli children and schooling in late July, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department P Waytha Moorthy, whose purview includes JAKOA, said people should recognise and respect Orang Asli culture and religion, and not try to assimilate them into other societies’ cultural and religious norms.

The minister added that there was the misconception that Orang Asli had no religion, and said Malaysians and politicians should be educated on their fellow countrymen’s spirituality.

ADAPTING TO URBAN LIFE

In urban areas, the Orang Asli communities face a different set of challenges.

Nestled among high-rise residences and commercial buildings of Damansara Perdana in Petaling Jaya, Desa Temuan was previously known as Bukit Lanjan Orang Asli reserve land.

According to residents, the Temuan villagers had originally resided in the middle of Kuala Lumpur around the Bukit Nanas area where the KL Tower stands, and migrated from one part of the Klang Valley to another, moving as development caught up with them, before settling in what is now modern Petaling Jaya.

In the late 1990s, the Bukit Lanjan land, where the Temuans were living in, was acquired by a local developer.

As compensation, in 2002 each household received either houses or apartment units in the new mixed development, along with monetary compensation as well as shares in a government-backed unit trust fund.

“Before this, the area here was mostly rubber lands or fruit orchards,” village chief Ismael Chat told CNA.

Nominally, his identification card states he was born in 1948, but Ismael gave his approximate age as 76.

He said the new roads that came with development made it much easier for villagers to get around. Yet at the same time, problems rose.

Many of some 1,000 inhabitants here are not Orang Asli, but outsiders and foreigners who have rented the single-storey bungalows from the Orang Asli owners.

“Many Orang Asli moved out if they could find land elsewhere, like nearby in Sungai Buloh, Gombak or Bukit Lagong (areas with forest reserves), and resumed their traditional lifestyle. They rent out their houses for extra income,” local village community management council chairman, Mr Firiszuan Sabri, 23, said.

Those who did not move elsewhere sought employment in urban Petaling Jaya, but city life is not cheap.

Mr Firiszuan said many houses are behind on their quit-rent.

“One issue is that we did not know how to manage the compensation we received properly,” he noted.

Many families were even worse off soon after, having spent their money and lost their traditional cultivation and forests on which they depended for food.

“But it’s honestly a challenge, balancing modernity with traditional lifestyles, we’ve lost many traditional skills, I can’t make traditional tools like a sumpit (blowpipe),” Mr Firiszuan said, adding that he could, however, survive in a forest if armed with a parang.

Likewise, Mdm Gelang Genus, a middle-aged Temuan lady, lamented that her skills in weaving traditional baskets from leaves are below par compared to her ancestors.

She could not produce the intricate, tightly-woven baskets on display in Desa Temuan’s customary hall, along with fish and river prawn traps as well as blowpipes.

“We just simply have no need to keep making these sort of items. Maybe once in a while when there’s a festival or just for fun, I’ll make some simple woven baskets, but nothing like these,” Madam Gelang said.

LITTLE ACCESS TO EDUCATION

Little access to education is a setback for the Orang Asli in general.

Schools in the interior are few and far from the Orang Asli villages, and children either travel long distances or stay in school hostels on weekdays.

NGO Suka Society noted that 7,029 indigenous children have never been to school in Peninsular Malaysia.

Out of 100 Orang Asli children who attend schools, only six complete their secondary education, it said.

In an earlier 2015 case in Kelantan, seven Orang Asli children ran away from their boarding school in Pos Tohoi, resulting in five deaths and two survivors discovered in a malnourished state after a search that stretched on for nearly 50 days.

A press conference by the grieving families of the seven children in 2018 saw them calling on the government to build primary schools in Orang Asli villages for the children’s safety.

Malaysia's first Orang Asli member of parliament Ramli Mohd Nor, who won the Cameron Highlands by-election in January, told the Malaysian Insight that bus operators were planning to stop sending Orang Asli kids to school in his constituency because they had not been receiving payment from the federal government since March.

At Dema Temuan, village council member Mdm Wan Mastini Ali said many of their teens were dropping out of secondary school and getting into social vices.

“The problem with our kids dropping out starts from primary level, and by the time they get into secondary school with students from other ethnicities, many kids are sent to the remedial or special education classes.

“This just discourages them, then they drop out and get into all sorts of social problems,” said Mdm Wan Mastini, 30.

Many youths get into drugs, ketum (a plant with opioid and stimulant effects), alcoholism or even prostitution, with some turning to petty crime to feed their habits, she added.

‘I WANT US TO BE FRIENDS’: JAKOA TO NGOS

Since his April appointment as the second Orang Asli director-general of JAKOA, academic Dr Juli has not had a day off.

He has been on the road touring the peninsula and visiting different Orang Asli villages in every state.

“I need to meet with the grassroots Orang Asli population, and the main problem is almost always the same everywhere – their lands are under threat, followed by infrastructure issues, and thirdly, late payment or subsidies from the government,” Dr Juli, a member of the Semai ethnic group from Perak, told CNA.

Issues such as the Kuala Koh deaths, or conflicts with loggers in Perak and Kelantan are also hotspots which he needs to keep an eye on.

“(The crises faced by the Orang Asli) arise more from their locations. It so happens that the Negritos are in the deep interior, so infrastructure, services and education are not easily delivered, causing them to fall behind compared to others.

“In other locations, the Orang Asli populations might have more development, but they still face problems in terms of education, income and development,” he said.

For JAKOA right now, the priority is mapping and surveying Orang Asli lands, and then applying for them to be gazetted as Orang Asli heritage land in their respective states.

Not many villages had been mapped out, he said, and for 2020, JAKOA plans to carry out community mapping for 150 villages, and the remainder in the 12th Malaysia Plan (2021-2025).

While JAKOA is facing funding and manpower challenges, Dr Juli expressed his confidence that the government would support JAKOA in helping to protect Orang Asli rights.

During a meeting with Malaysia Orang Asli Development Association in late June, Dr Juli said the agency only has 967 civil servants covering the entire peninsula.

“There are nearly 50 projects that JAKOA has planned, but only three people of the necessary grade to supervise these projects, from bridge construction, road access, community mapping and so on.

“I am requesting the NGOs to play a role, give us correct and strategic advice. Go ahead and criticise, but give me constructive criticism. If before this, NGOs held us as the enemy, now I want us to be friends,” Dr Juli told the Orang Asli attendees.

READ: First Orang Asli member of parliament in Malaysia

ACTIVISM AND AWARENESS

Malaysia has, in fact, made some progress in recognition of Orang Asli rights, compared to colonial and post-independence days.

“Back then, over 30 years ago, Orang Asli recognition was almost non-existent as far as their rights were concerned. The government didn’t have to ask the Orang Asli if they wanted to take their lands,” Dr Colin recalled.

“They just asked Orang Asli Affairs Department (JHEOA, before it was revamped and renamed to JAKOA) whether the project could go ahead, like the construction of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia or Kuala Lumpur International Airport, or the Sungai Selangor Dam.

“If the department said yes, it was assumed that the Orang Asli on those lands had consented,” he added.

Dr Colin recounted one case in Cameron Highlands, where the rubber tree plantation of the Kampung Corner residents was taken over and turned into reservation land.

“In the typewritten agreement I sighted, it was stated that the government would pay RM24 per rubber tree, and that copy had the ‘4’ whited-out, making it RM2 a tree. Until now that RM2 is still not paid,” he claimed.

These days though, Orang Asli have become more and more aware of their rights.

In 2002, the Selangor Temuans living in Bukit Tampoi sued the state government for forcibly evicting them from their customary land for development.

The High Court ruled that the Temuan plaintiffs held native title to the land, according to common law, having proven that they practised their indigenous culture on the land in question.

On June 20, Kampung Tasik Asal Cunex Hulu Air Denkal network chairman Pam Yeek, with the assistance of environmental NGO Association for the Protection of the Natural Heritage of Malaysia (PEKA), filed a civil suit against the Perak state government over the encroachment into their land.

Recently, the federal government under the Pakatan Harapan has become more proactive on behalf of the Orang Asli, such as filing a civil suit against the Kelantan state government to seek the legal recognition of native land rights for the Temiar Orang Asli in Pos Simpor.

Other cases that have gone the Orang Asli’s way in terms of protecting land rights include a recent High Court decision to strike out a durian plantation’s suit against Temiars living in Gua Musang for erecting a blockade preventing the plantation from encroaching on the Temiars’ native customary land.

READ: Activists, TV crew detained at anti-logging blockade in Kelantan

Lawyer and human rights activist Siti Zabedah Kassim, 55, said moving forward, there should not be any more grabbing of Orang Asli’s ancestral land.

The co-deputy chairman for the Malaysian Bar Council’s committee on Orang Asli rights, said the situation was tricky as land administration in Malaysia is placed under the respective state governments.

“What we as the public can do is to understand and support the Orang Asli community’s fight for their land and rights, especially with regards to their ancestral and customary lands in the forest.

“And we need to demand the government to look after the Orang Asli rights,” Mdm Siti added.

"I HAVE A VOICE TOO"

This growing awareness of the Orang Asli rights is not just restricted to land rights.

Of late, Orang Asli women have also arisen to speak out against what they see as interference in their choice of religions and reproductive rights.

Ms Nora Awa, 32 a Temiar living in Gua Musang, Kelantan, became an activist advocating for indigenous and native land rights after attending a Jaringan Orang Asal Semalaysia (JOAS - The Indigenous Peoples Network of Malaysia) workshop on advocacy a decade ago.

“Previously, I just stayed in the village, I was really afraid to voice out, but after the NGO and activist programmes, these opened my mind, and made me realise I have a voice too.

“If we sit silent and wait for the government to take action, or leave it just to the menfolk to make noise, it would be difficult to advance our cause, maybe our case might not even be taken up,” Ms Nora said.