Dying indigenous cultures? These young Malaysians are fighting back with music and art

Musician-artist Alena Murang and contemporary artist Kendy Mitot are racing against time to bring back the old traditions and customs of Sarawak’s minority tribes.

Malaysian artists Kendy Mitot, who is Bidayuh, and Alena Murang, who is part-Kelabit, are trying to revive their indigenous Sarawakian heritage through art. (Photo: Kendy Mitot, Lee Man Yee)

KUCHING: On a cool Sunday night, people have gathered expectantly for a concert at the city’s open-air amphitheatre.

Many are here to see some of Sarawak’s famous musicians perform, such as rocker Noh Salleh and R&B singer Dayang Nurfaizah. But before their homegrown heroes in Malaysia’s pop music scene appear, two unassuming people in tribal wear step out carrying unusual stringed instruments.

One of them is Alena Murang, a Kuching native who has been making a name for herself playing the sape, a traditional lute used in the island of Borneo.

Together with her long-time mentor and sape master Mathew Ngau Jau, the 27-year-old launches into a series of songs from Kelabit, her father’s tribe, to a smattering of polite applause from an audience fed on a diet of pop and rock music.

It’s a tough crowd but that hasn’t stopped her from reaching out to people. Aside from Sunday night’s gig as part of the first Rainforest Fringe Festival (RFF), Alena has also been playing short sets at some of the city’s bars. On Friday, the annual Rainforest World Music Festival beckons.

Alena isn’t the only young Sarawakian valiantly trying to bring her indigenous culture to a mainstream crowd this week.

Elsewhere, 30-year-old contemporary artist Kendy Mitot is presenting art installations based on his own Bidayuh heritage – and he admits feeling nervous about it.

The Kuala Lumpur-based artist is exhibiting in Sarawak for the first time, and he’s not sure how people will react to the works, which are swathed in mysticism and ancient traditions frowned upon by some.

“It’s very tough to make people like artworks like these,” he told Channel NewsAsia. “But it comes from a dying culture, and I just want to share my knowledge in a contemporary way.”

The Bidayuh and Kelabit are among the many indigenous minority groups in Sarawak.

While the former is the fourth largest ethnic group in the East Malaysian state, they actually make up only eight per cent of the population. Meanwhile, there are only 6,000 Kelabit people combined, in both Sarawak and Indonesia’s northern Kalimantan, south of the border.

A RACE AGAINST TIME

For both artists, saving the rich heritage of their respective indigenous groups has been a race against time.

Alena, whose father is a Kelabit and mother is an English-Italian anthropologist, began learning the sape, an instrument traditionally played only by men, at the age of 13. And only out of sheer necessity.

When she was six, she and her cousins would perform traditional dances at small functions in Kuching. But there weren’t many sape players to accompany them.

“Sometimes, we’d just perform to that one CD everybody had,” she quipped. “When I started playing the sape, almost no one was learning it. Even from my dad’s generation, hardly anyone was playing it.

Meanwhile, Kendy grew up still surrounded by the traditional rituals of the Bidayuh tribe in Bau, a gold mining town just 45 minutes from Kuching. In fact, his late grandmother was a shaman.

But today, there’s a catch. “They’re all old already. I think less than 30 people still practice these kinds of rituals, and most of them are from 65 to 90 years old. This year, already two have died. I think it’s too late. It’s a dying culture.”

CLASH OF CULTURES

The disappearance of such rituals has been the result of cultures clashing. Since the missionaries arrived in the 1860s, the Bidayuh have been staunch Christians who often frowned upon old rituals and ceremonies.

“After you convert, you cannot touch these things,” said Kendy, who is a Christian himself.

“In my area, they throw away all the ritual objects and traditional art into the river. Some are burnt. Religion in itself is not a problem, but when people who practice them say ‘you cannot do this or that’, then that becomes a problem. If you’re a first-time convert, you become scared of these (objects).”

Alena recalled a similar situation when she was growing up among the Kelabit, who were also Christians.

“When I was younger, some of the old aunties and uncles weren’t that happy when they saw us learning some of the songs, which could be about headhunting or a love song calling out to different lovers to lie with you,” she said.

A TURNING POINT

But as both artists grew up, they also realised they belonged to a unique heritage.

After finishing her business degree in the UK, Alena spent a couple of years in management consulting in Kuala Lumpur before shifting careers to become an artist.

Following a one-year stint at Singapore’s LASALLE College of the Arts, she joined the Malaysian percussion group Diplomats Of Drum on a two-month tour of the US in 2014.

“From there I realised so many people were interested in the sape. They’ve seen all these ‘exotic’ instruments like the sitar or the ukulele from Chile but it was like, ‘where’s Borneo?’” she recalled.

Despite aiming to be a full-time visual artist, it was her sape playing that drew attention. After doing small gigs and open mic sessions at bars in KL, she was invited to bigger events and festivals, and even got a government grant to teach sape.

Meanwhile, the turning point for Kendy was taking up an art degree a decade ago, when he eventually realised that tapping into the objects, artefacts and rituals of his youth could be a way of preserving his cultural identity.

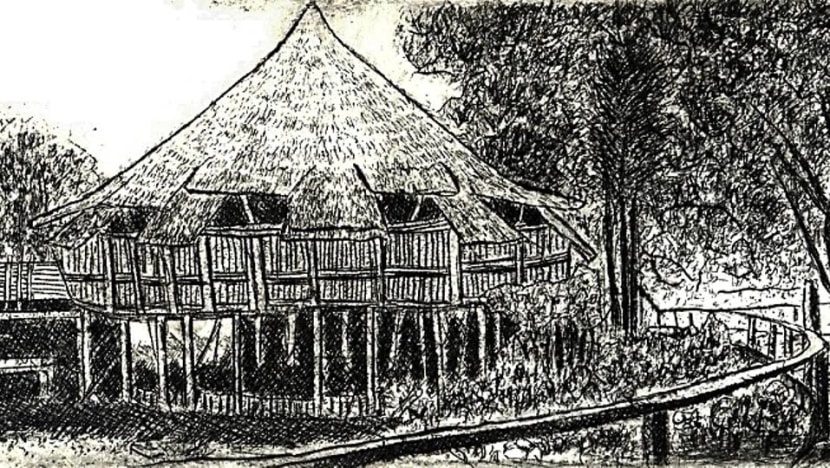

Among the exhibitions at the RFF are his mixed media installations that reinterpret objects from Bidayuh rituals. One of these uses tribal totems called tipaduak, which are only usually put in front of longhouses to protect against evil spirits. For the show, Kendy recreated and assembled them together as a statement of protecting his indigenous culture.

“I’m very lucky that I studied fine art because if not, I won’t be doing this kind of thing,” said the artist. He added wistfully: “When you’re young, you don’t think these things are important, and now, I keep thinking why I didn’t start documenting this earlier.”

INVOLVING THE COMMUNITY

The two artists have since been seriously learning more about and promoting their indigenous cultures.

Twice a year, Alena makes the long trek from KL to the remote settlement of Long Peluan, where her father’s family are from, to learn the songs and stories from the Kelabit elders.

“They’re realising we’re slowly losing these and not many people are singing them, so they’re quite happy to share some of these pre-Christian songs.”

Her painstaking efforts have resulted in her first album, Flight. Released last year, it comprises a handful of songs from the Kelabit and Kenyah tribes.

“I don’t write my own songs on sape. For me, it’s important to keep the old songs alive and there’s still so many that I have to learn and share,” she said.

Kendy’s own Bidayuh people, too, have slowly come to accept his efforts – and it has extended beyond art-making.

Thanks to his father, who’s the kampong chief, there’s been a revival of their annual festival, called Gawai Bidayuh. While it’s not quite the real thing, it’s still a nice symbolic gesture that has been going on for the last couple of years.

REACHING OUT TO MALAYSIANS

While their communities are now coming on board, it’s been slow-going outside, said Kendy.

Until quite recently, there was also a stigma attached to any kind of art with “indigenous” trappings in Malaysia. He recalled how, in 2015, galleries would dismiss his works saying these wouldn’t sell.

A recent exhibition of indigenous art at Galeri Petronas in Kuala Lumpur is a sign that things are slowly changing, but he reckons there’s still much to do in terms of raising awareness in Malaysia, especially from the peninsula.

“Most of them still don’t like to see these kinds of indigenous art, much less know about Sarawak or Sabah tribes. In the college where I teach, my students first thought I was Malay. And when I told them I was a Bidayuh, they asked me what it was. They only know Malay, Chinese, and Indians.”

Things seem to be much better when it comes to music. In fact, the last few years have seen a surge in interest in the sape.

“People want to use in movies, documentaries, and ads. They want to learn how to play it and even include it in their rock songs,” said Alena, who has formed a sape collective with other musicians, and was even invited by Malaysian rock band Estranged to join them for their live shows.

And it doesn’t end with the younger generation embracing sape. Alena also started an organisation called Art4, which aims to give back to the people from whom she has learnt so much.

“One of the things we do is connect indigenous musicians and artists with more contemporary events and spaces. I want it to become the hub that people go to when they want indigenous artists,” she said.

“Music or art was not meant for fame or money. It’s meant to pass down knowledge and certain values, tell stories, and bring communities together.”