How Fujifilm survived the digital age with an unexpected makeover

Once a photo film giant, it found surprising new applications for its technology. Inside The Storm tells the story of how it became a thriving player in healthcare and cosmetics today

Fujifilm's foray from photo film to cosmetics, with Astalift, helped save the company in the digital age.

TOKYO: As a scientist with Fujifilm, Tomoko Tashiro was tasked with developing technology about coloured photo paper.

But when she returned to work after maternity leave in 2005, she was in for a big surprise. She was asked if she would like to venture into cosmetics - under the same company.

“I was shocked. I was unsure whether the project could be done or not,” said Ms Tashiro. “Everyone was worried about how the (company’s technology) could be applied in fields such as cosmetics and supplements.”

Today, cosmetics and healthcare are the company’s most profitable divisions, contributing more than US$3.4 billion (S$4.8 billion) of revenue every year.

The will to make such drastic changes and adapt quickly to market shifts is what has kept Fujifilm - once a giant of film photography - alive and thriving when the digital age came a-knocking, even as its rival Kodak became a famous casualty and object lesson in failure to innovate.

WATCH: A film giant’s transformation (2:26)

The inside story of how Fujifilm completely transformed its business is told on a recent episode of Inside the Storm: Back from the Brink, a series about legacy companies that have rebuilt themselves from near-bankruptcy.

(Read our earlier stories: How a rookie brought Lego back from the brink, and Nintendo fights back.)

NO CHOICE BUT TO CANNIBALISE

Founded in 1934, for decades the company enjoyed a near-monopoly on photo film in Japan.

When the first wave of digitalisation arrived in the 1980s, it was only felt in the business-to-business markets. Fujifilm appeared to be ahead of the curve, providing digital X-ray to hospitals.

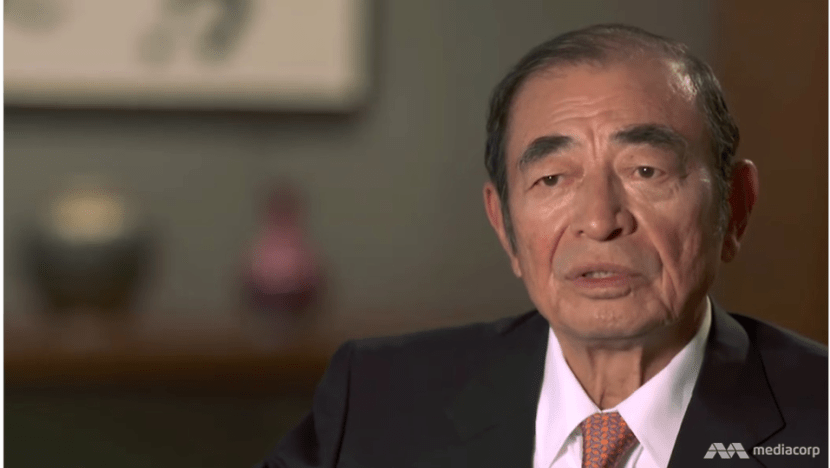

Chairman and CEO Shigetaka Komori said the company decided not to reject digital technologies despite the fact that it was “cannibalism - we would eat into our own analogue division”.

He explained: “If we wouldn't do it, somebody else would. That's why I decided we should enter digital and become a player in digital.”

In 1988, the company released the world’s first fully digital camera: The FUJIX DS- 1P.

It could store five to ten photographs on its memory card and boasted a 1.1 megapixel resolution. But it was expensive, costing more than US$10,000, and was mainly used by professionals in the magazine and newspaper industry.

Mr Komori said: “This was not a price that a regular amateur would be able to pay… and there was a problem with resolution. So digital photography could never catch up with normal photography.”

The company thought it was ahead of the curve but the digital age hadn’t truly arrived yet. Incredibly, the photo film market continued to grow. By 2001, two-thirds of the company’s profits still came from photo film.

Fujifilm abandoned its new business ventures, despite having pioneered the digital camera a decade earlier. The company felt that the printed picture would survive and invested millions in the Instax Mini, an analogue camera that allowed one to take a picture and print it in seconds. It sold over a million units in 2002.

STOLEN AWAY IN AN INSTANT

But then, the long-awaited digital age finally arrived in 2003 - and hit the company hard.

Sales of photo film plunged by a third in less than a year. In just six months, shops went from processing almost 5,000 rolls of film a day, to fewer than 1,000.

A market that had accounted for two-thirds of the company’s profits had disappeared in the blink of an eye. Mr Komori said: “At first I thought that colour film wouldn't disappear easily, but digital stole it all away in an instant.”

To add to the company’s woes, another disruptive technology emerged - the mobile phone. This revolutionised digital photography. Digital photographs were cheaper and speedier, and Facebook, Instagram and Twitter became the new pioneers of photography as smartphone sales skyrocketed.

Drastic changes were needed at Fujifilm.

First to go were its film manufacturing plants, along with the painful decision to cut some 5,000 jobs.

The firm slashed costs by more than US$5 billion in the process. But the company still faced an enormous battle to generate new income.

BEYOND FILM, TO SKIN CARE AND PHARMACEUTICALS

Mr Komori came up with a revolutionary battle plan to diversify into the pharmaceutical, healthcare and cosmetics industries. These seemed completely incongruous to photography, but Fujifilm always knew that its technology had the potential for applications outside of photography.

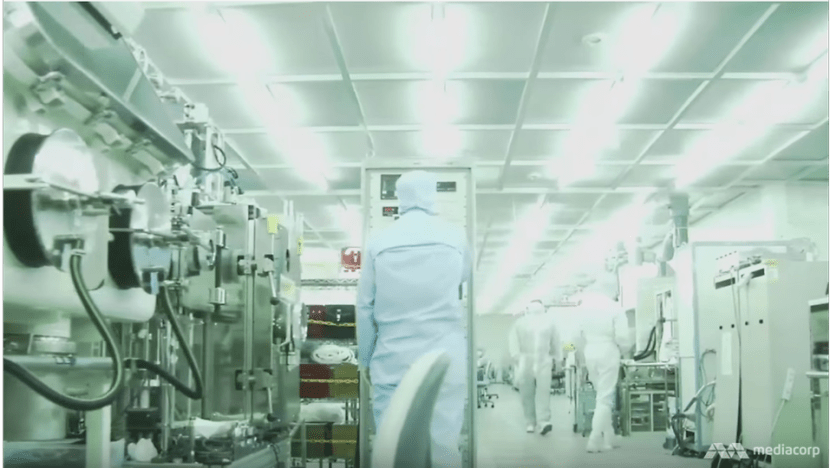

The company had amassed some 20,000 chemical compounds over nearly a century of research. All were originally developed for photo film, but would now be the ingredients for Fujifilm’s new pharmaceuticals division.

And in the cosmetics division, the firm used the same processes and chemicals that had earlier helped to prevent the fading of colours in photography to apply to skin - preventing it from sagging and fading.

Assistant Professor Sampsa Samila of NUS Business School marvelled: “To be able to use this idea, to be able to take the same chemicals expertise and apply it in completely different industry, is a fabulously interesting insight.”

Currently, the company is developing drugs to combat cancer and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and infectious diseases.

Mr Komori’s strong leadership and foresight saved and transformed Fujifilm from a photography company into a diverse scientific enterprise.

These days, photo film, which once accounted for 70 per cent of the company’s profits, now represent less than 1 per cent. But then why continue to make it at all?

Mr Komori said that the firm would always protect the photography culture and keep it alive. “The culture of photographs is one that mankind can't do without,” he said.

“We don't make any money out of it, but we still keep making colour film. No matter what, we will not get rid of photography.”

Watch the full story of Fujifilm on Inside the Storm: Back from the Brink here.