IN FOCUS: The ongoing struggle to reduce air pollution in Jakarta and why the problem has persisted

Jakarta’s poor air quality prompted a group of residents to sue the government and they won. CNA explores the root causes and impacts of the smog which regularly blankets the city.

Jakarta regularly ranks as one of the most polluted cities in the world by air quality monitoring organisations. (Photo: Nivell Rayda)

JAKARTA: It has been months since Andy Rahman last rode his bicycle on the streets of Jakarta, a hobby he picked up last year when non-essential workers like himself were told to work from home to curb the spread of COVID-19.

“After about 30 minutes, my eyes were burning, my throat hurt and I began to cough,” the 47-year-old marketing manager told CNA.

The coughing would persist even after he got home. It would only go away after he remained indoors for hours, he said.

Rahman noticed that whenever he went cycling, the air would smell like there was something burning. Visibility was sometimes so low that tall skyscrapers appeared as mere silhouettes against a greyish sky.

This led him to suspect that his coughing had to do with the worsening air quality.

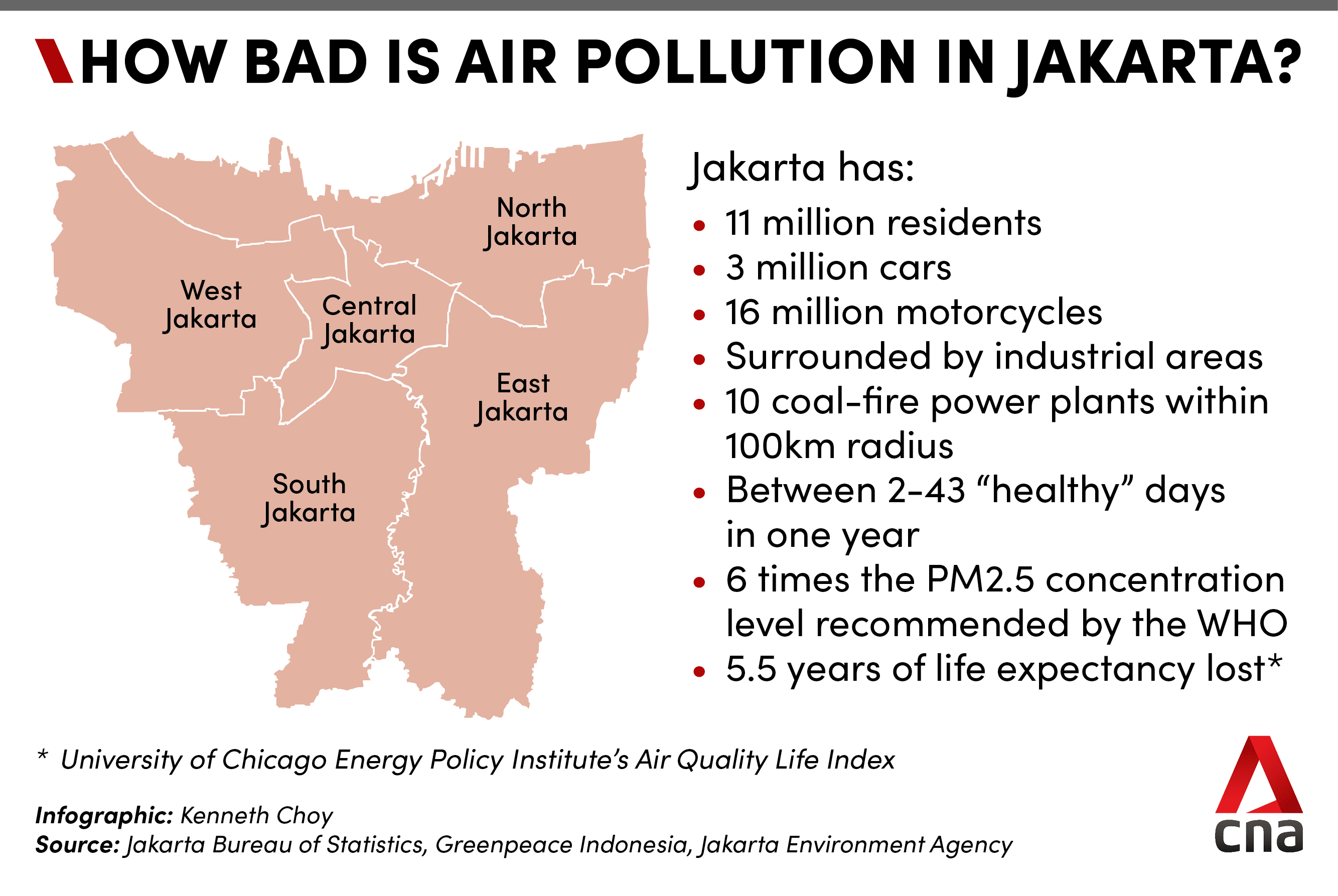

According to air quality monitoring tools, the city of 11 million people consistently ranks as one of the most polluted cities in the world.

Data from the Jakarta Health Agency shows that in 2019, before the pandemic began, the city only had two days when the air quality was deemed “healthy”. The rest of the year, the city was blanketed with toxic fumes and fine dust particles from vehicles, factories and coal-fired power plants surrounding the capital.

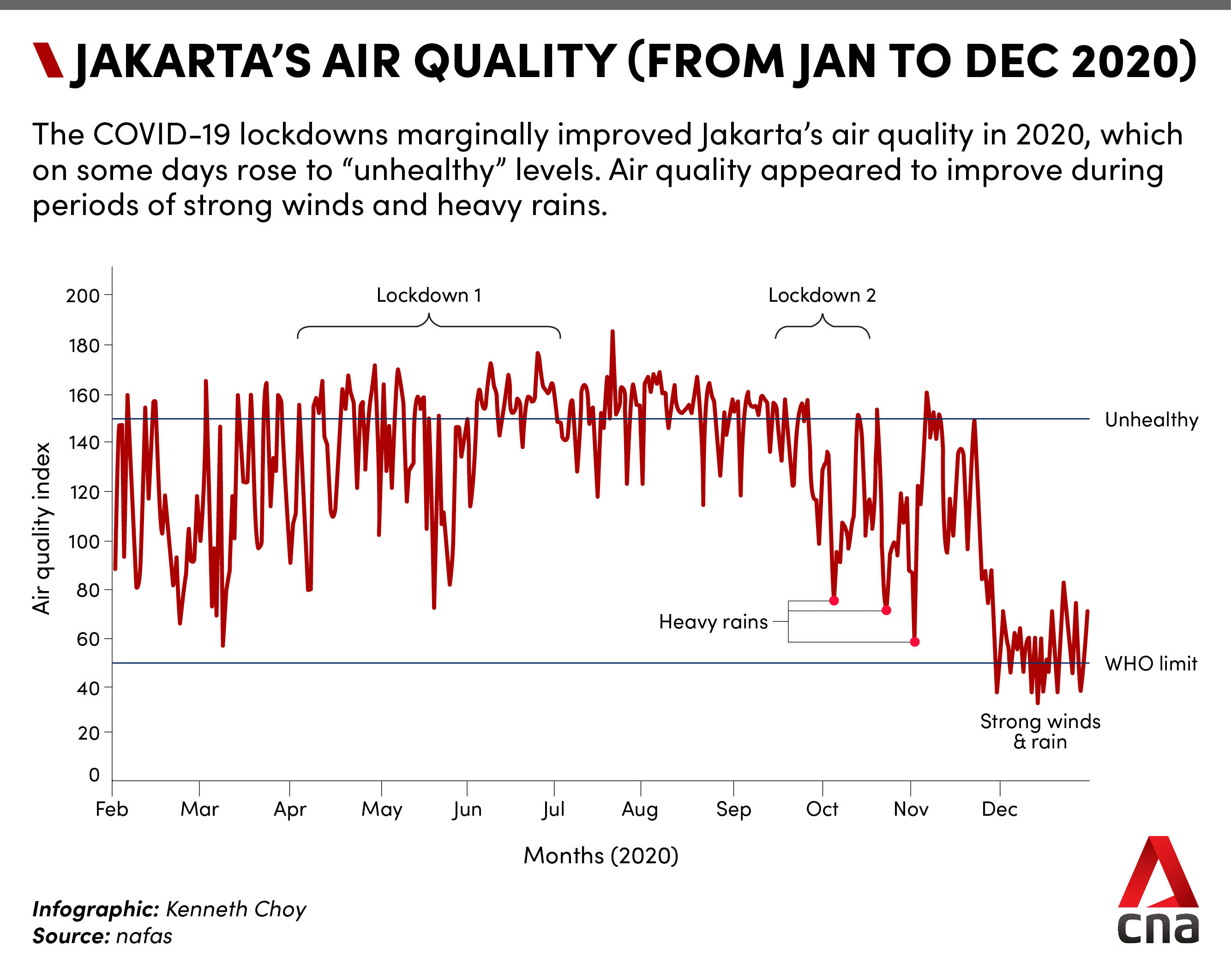

In 2020, despite the introduction of various mobility restrictions to curb the spread of COVID-19, the number of healthy days only grew to 29. Since then – as activity restrictions were lifted – the air quality has gradually returned to the way it was before the pandemic.

At the suggestion of his wife, Rahman stopped cycling outdoors, opting to exercise at home instead. “And it worked. The coughing stopped,” he said, adding that a few of his cycling buddies had also experienced the same health problems.

“Perhaps because I was born and raised in Jakarta, I never realised just how bad things are. We breathe every few seconds and yet we rarely realise what the air might contain and what effects (the pollutants) might have on our bodies,” Rahman said.

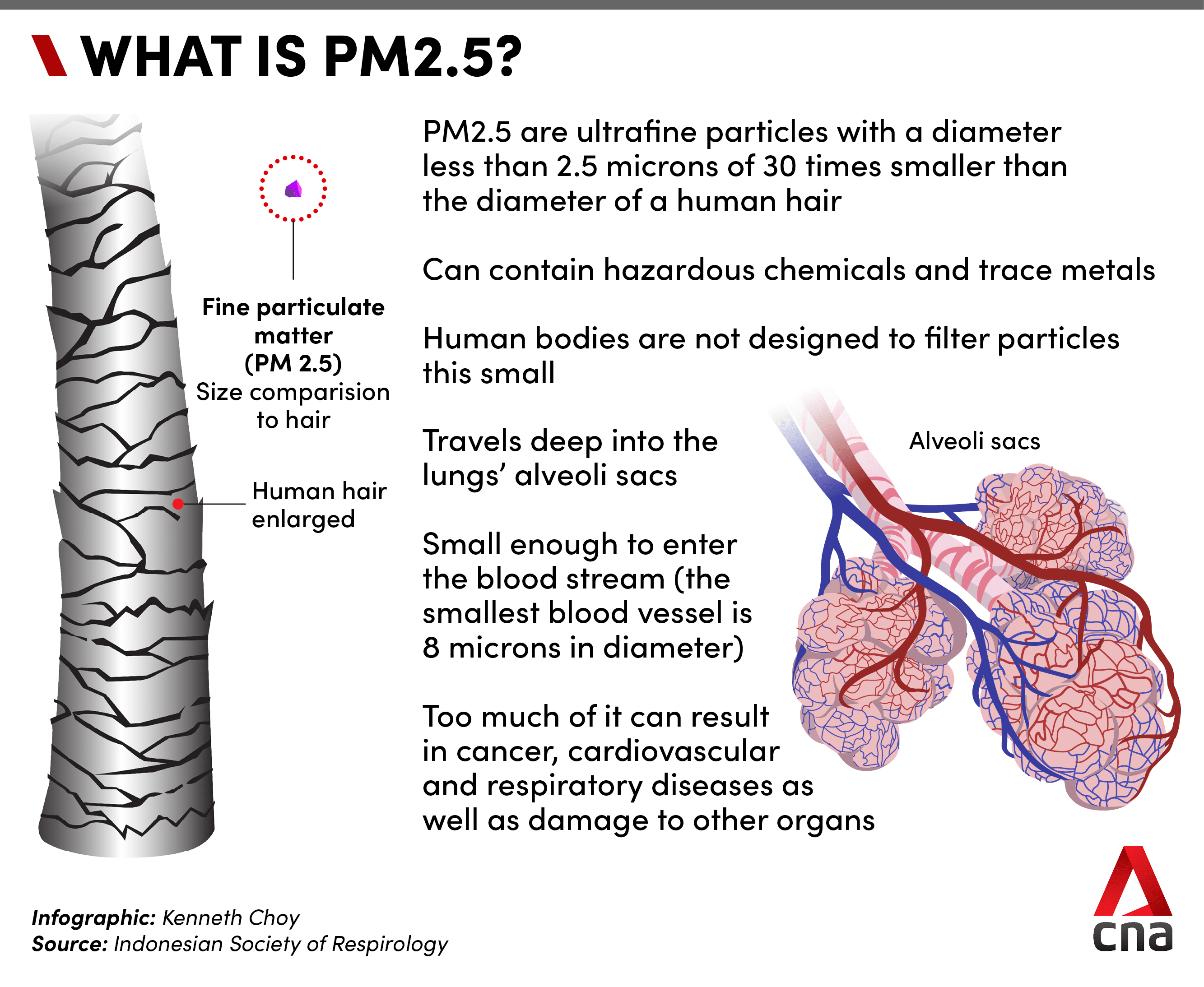

Jakarta’s air regularly contains unhealthy levels of harmful gases like carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and ground level ozone as well as particulate matter (PM) which can comprise various chemicals.

Measuring less than 2.5 microns or 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, PM2.5 can enter the bloodstream and accumulate in various parts of the human body. This can result in cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. It can also affect other organs.

In its annual Air Quality Life Index study, the University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute said on average the residents of Jakarta are exposed to more than six times the PM2.5 concentration level recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The institute estimated that Jakartans could gain 5.5 years of life expectancy on average if the city’s air quality complies with the WHO guideline.

In 2019, 32 city residents sued President Joko Widodo, three of his ministers as well as the governors of Jakarta and neighbouring provinces Banten and West Java.

On Sep 16, two years after the lawsuit was announced, the Central Jakarta District Court passed down a landmark judgment, finding the government guilty of “committing unlawful acts” by failing to uphold citizens’ rights to clean air and failing to combat air pollution in the capital.

The forest and environment ministry has stated that it is appealing the decision.

What are the root causes of air pollution in Jakarta? Those interviewed by CNA said that vehicles and factories are among the main culprits. The problem is compounded by an emission monitoring and enforcement system which appears to be inadequately equipped for such a vast metropolis.

As the situation drags on, the possible long term impacts on public health are very real.

VEHICLE EMISSIONS THE BIGGEST CONTRIBUTOR TO POLLUTION

Jakarta is regularly listed as one of the most congested cities in the world in the annual traffic index prepared by technology company Tom Tom. Every day, around 20 million vehicles compete for space on its 6,500km of streets and roads.

The vehicles – including those owned by people who live in Jakarta’s suburbs and have to commute to the city – not only contribute to crippling traffic congestion. They also emit toxic fumes and dust particles that pollute the air.

According to a study conducted by global health organisation Vital Strategies, which was released in September last year, between 32 per cent and 57 per cent of air pollution in Jakarta is caused by vehicle emissions.

Irvan Pulungan, the Jakarta governor’s special envoy on climate change, said the city is trying to introduce a number of policies to control air pollution caused by vehicles.

“The issue of air pollution has been something of great concern to us. In Jakarta, it is an issue which we are trying to address on a regular basis,” Pulungan told CNA.

He said that in 2019, the city government mandated all private vehicles to pass emission tests. Under a trial run project, those that do not pass the test will have to pay higher parking fees.

He added that the authorities are also establishing low emission zones, where vehicles with high emissions will not be able to pass through.

“We cannot stop people from using their cars but we are disincentivising them through these policies,” said Pulungan.

However, participation for the emission test has been low.

In 2020, Jakarta was home to three million cars and 16 million motorcycles. However, that year, only 13,019 vehicles participated in the emission tests organised by the city government, according to data from the Jakarta Environmental Agency.

The municipal government is trying to get more cars and motorcycles to undergo the emission tests. Starting next year, the Jakarta police plans to conduct raids and impose a fine of 500,000 rupiah (US$35.18) for cars and 250,000 rupiah for motorcycles which fail to meet emission standards.

The environment ministry’s director for air pollution, Dasrul Chaniago, acknowledged that vehicle emissions are the biggest contributor to Jakarta’s bad air quality.

“We are utilising technological developments to control emissions from vehicles,” the director told CNA. “For example, we used to have leaded fuel but back in 1996, we devised a programme to phase out leaded fuel.”

The latest step was to adopt Euro 4 emission standards for new cars and motorcycles in 2017. “We were supposed to adopt Euro 4 (emission standards) for diesel-powered vehicles in February 2021 but because of the pandemic, we postponed it to April 2022,” he said.

Related:

Ahmad Safrudin, chairman of the not-for-profit organisation Leaded Gasoline Eradication Committee (KPBB) said that Indonesia’s emission standards were already lagging behind some of its Southeast Asian neighbours.

Malaysia for example has been applying Euro 4 standards for petrol since 2015 and diesel since 2018 while Thailand adopted the Euro 4 standards for both petrol and diesel in 2012. Meanwhile, Singapore has been applying the stricter Euro 6 standards since 2017.

Safrudin also highlighted that in Indonesia, the Euro 4 emission standards only apply to cars and motorcycles manufactured after the 2017 regulation was passed. Meanwhile, older vehicles which do not meet the requirements are still allowed to be on the roads.

Furthermore, retailers are still offering petrol and diesel brands which fall within the outdated Euro 2 standards set in 2007. These fuels include those marketed under the brand Premium. They are among the most affordable and least environmentally friendly options available to vehicle owners.

“These fuels have high emissions and have an extraordinarily massive impact on the environment,” Safrudin told CNA. “We keep selling them in defiance of our own regulation. When you have a new regulation forcing you to adopt new technology, the fuels (that are being) sold need to keep up.”

Puji Lestari, a professor on environmental engineering from the Bandung Institute of Technology said that with the number of vehicles in Jakarta growing every year, it is important for the government to ban fuels that are damaging the environment.

“We can already reduce air pollution significantly just by forcing people to use good fuel,” she said.

State-owned oil company Pertamina, which has been selling the brand Premium since 1983, said in August that it plans to completely stop selling the product by 2024.

The subsidised fuel, Pertamina president director Nicke Widyawati told reporters, is currently sold at 30 per cent of its outlets. This means it is less readily available to the majority of its customers.

Environment ministry director Chaniago blamed the consumers for continuing to use highly pollutive fuels. “We have already provided good fuel brands, but there are people who choose the bad fuels even though they are not only bad for the environment but also bad for their vehicles,” he said.

FACTORIES, POWER PLANTS ALSO CULPABLE

The industries are also to blame.

Highly pollutive fossil fuels are also being used by thousands of factories and power plants in and around Jakarta.

In one industrial area, around 90 minutes drive from the heart of the city, smelters and petrochemical companies regularly churn out greyish smog so thick that they look like scenes from a forest fire.

Meanwhile, to keep up with the factories’ high demand for electricity, coal-fired power plants have to work round the clock, belting out black smoke which towers high into the atmosphere.

Hazardous gases and particles produced by these factories and power plants can travel hundreds of kilometres to places like Jakarta. With the Indonesian capital being surrounded by industrial areas, the city is bound to fall victim to such trans-boundary air pollution no matter which direction the wind blows.

Environment ministry director Chaniago said his office is doing all it can to make sure emission levels from factories are being lowered.

“We continue to tighten the regulations. In 2019, we imposed stricter emission standards for the cement industry. Recently, we updated the standards for the fertiliser industry. That is how we keep improving the air quality. It is an ongoing process,” he said.

Lestari, the environmental engineering professor, noted that although there are regulations which dictate how much emission factories can produce, the enforcement is a different matter entirely.

“By law, the industries have the obligation to self monitor and report their findings to the ministry. In short, they measure their own emissions,” she said.

“How can we be sure that they do their monitoring correctly or be truthful in their report? It all depends on the goodwill of the industry players. There are many loopholes that they can exploit. We need a more rigorous system to monitor industries.”

Chaniago of the environment ministry said the self-reporting requirement stems from the fact that the ministry does not have the manpower to monitor thousands of factories operating across the vast nation.

“But we do conduct surprise inspections to make sure that the data they have presented is consistent with what we find in the field,” he said.

Others are sceptical about the ministry’s efforts.

Bella Nathania, a researcher from the Indonesian Centre for Environmental Law (ICEL) remarked: “The ministry always says that it regularly conducts monitoring, evaluation and inventory but when judges (at the air pollution lawsuit) asked them to present to the court the results of these evaluations, they could not produce a single document.”

“They also claimed to have tightened the emission standards for power plants and factories. But during the trial, they couldn’t produce the exact figure of how many companies have complied with the regulations and how many have been sanctioned.”

Bondan Andriyanu, Greenpeace Indonesia’s climate change and energy campaigner, believes that most factories are actually capable of lowering their emissions.

“Some of these companies are multinational companies. Some are Indonesian companies with international investors. These international companies apply double standards because they manage to keep emissions low in their own respective countries but they wouldn’t do the same here in Indonesia,” he said.

Andriyanu posited that the main reason for this is that regulations in Indonesia are more lenient compared to other countries. For example, the acceptable level for PM2.5 over a 24-hour period in Indonesia is 55 micrograms per cubic metre. The recommended WHO guideline issued in 2021 is only 15 micrograms per cubic metre.

EMISSION MONITORING NEEDS TO BE IMPROVED

Those interviewed by CNA also said that improvements can be made to the overall emission monitoring system.

The environment ministry collects its air quality data from just two monitoring stations. One is situated in a sports complex surrounded by dense vegetation, while the other is at a ministry facility in Central Jakarta.

The city government also operates five monitoring stations spread across its five municipalities. These stations are not linked to the ones operated by the ministry.

“We have different IT systems so it is a bit tricky to get them all to work together,” Chaniago said of the monitoring stations operated by both the ministry and the city administration. “But we support each other. We regularly share data and compare notes.”

Related:

The air pollution director admitted that for a city with the size and population as big as Jakarta, there should ideally be 30 monitoring stations.

The lack of monitoring stations is what inspired Piotr Jakubowski to launch air quality monitoring platform Nafas last year. The company now boasts 130 air quality sensors across Jakarta and its surrounding suburbs.

They collect Air Quality Index (AQI) data in real-time. The AQI was developed by the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency.

“Two years ago, or even a year before Nafas was launched, you would have very spotty air quality data. They only collect data at certain times of the day,” Jakubowski told CNA.

“Real time data is really important. We have to make neighbourhood level air quality data accessible to everybody. Air quality data is like the blood (analysis) for the health of our city.”

While the government operates big, expensive machines which can collect air quality data from a 5km radius, Nafas sensors are smaller, more affordable and can only cover a radius of 1km.

“There is a lack of data in the first part and then there’s a lack of understanding on the issue. We felt that by having a sensor in every single neighbourhood ... we are trying to make people realise that air pollution is not just a downtown Jakarta problem,” he said.

Andiyanu of Greenpeace said there is no reason why the bulky and expensive monitoring stations operated by the ministry cannot co-exist with the smaller sensors owned by air quality monitoring firms like Nafas.

The activist noted that other countries rely on both types of sensors as references for scientific research and policy making.

“The equipment the government is using also has its limitations. There are so few of them, they cannot cover the entire city. The smaller sensors may have less range, but because there are many, they paint a near accurate picture of what is going on,” he said.

A related issue is the type of data that is being collected and analysed.

Andriyanu noted that the Indonesian government is not using the globally accepted AQI to track pollution levels. Instead, it uses its own measurement called the Air Pollutant Standard Index (ISPU).

According to the 1997 regulation on ISPU, the index only measures carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, ground level ozone, nitric dioxide and particulate matter with a diameter of 10 microns, known as PM10. The index does not take into account the levels of PM2.5 in the air in their measurement, unlike the AQI. The ISPU is measured daily instead of real time like the AQI.

“Another difference is the ISPU only categorises the air quality into healthy, moderate, unhealthy and very unhealthy. It does not have the ‘unhealthy for sensitive groups’ category found in AQI,” Andriyanu said.

“The government always says that on average (Jakarta’s) air quality is moderate. We don’t know if that is actually true or if it is actually unhealthy for sensitive groups.”

“AIR POLLUTION IS LIKE A SILENT KILLER”

Agus Dwi Susanto, chairman of the Indonesian Society of Respirology said with high levels of air pollution, the health impacts can be immediate.

“(Air pollution) can cause eye irritation, runny nose, sore throat, cough as well as acute respiratory infection. Pollution reduces our local immune system, that’s why some people can experience acute respiratory infection,” he said.

The effects are more severe for people with pre-existing medical conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive breathing disease. “When exposed to air pollution, they will experience asthma attacks,” the pulmonologist added.

Susanto said he is conducting research which links air pollution with the number of patients visiting the Persahabatan Hospital in East Jakarta where he works. Persahabatan is the referral hospital for patients with respiratory diseases.

“If you look at the charts, the increase in visitations is in line with the increase in air pollution. If pollution goes down, visitations decrease,” he said.

Related:

But it is the long term effects of air pollution that the doctor is more worried about.

“When there is a low concentration of pollution, we won’t feel it immediately. We will feel the effects after years of getting exposed. We can say that air pollution is like a silent killer,” he said.

In his 2013 research, Susanto found that out of the 300 lung cancer patients surveyed, 4 per cent of the cases can be attributed solely to air pollution. “These patients do not smoke, but they do spend most of their time outdoors and therefore the only explanation is the bad air quality that they breathe,” he said.

In another study, the pulmonologist discovered that out of 153 street sweepers he surveyed, 10 had suffered respiratory illnesses like asthma and chronic obstructive breathing disease.

“The prevalence is two and a half times higher among street sweepers in Jakarta than their counterparts in rural areas. There is a correlation between the high prevalence and air pollution.”

Budi Haryanto, a professor on public health from University of Indonesia said the pandemic has created a double whammy for people living in highly polluted cities like Jakarta.

“When we are exposed to polluted air for a long period, the accumulating pollutants can cause damage to our body and develop into chronic illnesses. If we are infected with COVID-19 and have these pre-existing conditions, our immune systems which normally have to battle these chronic illnesses now also have to fight COVID-19,” he said.

A compromised immune system will not only cause people to be more susceptible to COVID-19 but can exacerbate the effects of a coronavirus infection, the public health expert cautioned.

A recent study conducted by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 was closely associated with more than three times the odds of being mechanically ventilated and twice the likelihood of a stay in ICU among the more than 2,000 COVID-19 patients surveyed.

Meanwhile, a study from Harvard University suggested that there is a positive association between higher historical PM2.5 exposures and higher county-level COVID-19 mortality rates in the United States.

But the pandemic does have a silver lining: more people are realising the importance of wearing face masks in public.

“One way to reduce the impact of air pollution is to wear personal protective equipment like face masks,” Susanto said. “However, you need face masks which are able to filter out PM2.5 particles. Even then, they cannot protect you from hazardous gases. So you still need to exercise caution.”

IS THERE HOPE?

For now, there seems to be no escaping Jakarta’s bad air pollution.

Air quality data provided by monitoring company Nafas shows that in the middle of the night and early morning, the pollution level is not much better as compared to day time when streets are congested and factories are operating.

At night, gasses and particles hovering high in the atmosphere will descend to the surface as the air cools.

The only respite comes during periods of high winds when the pollutants are blown away, or when there are heavy showers and the contaminants are washed into the ground.

“Jakarta is very dependent on rain to clean air pollution. We get clean air because of the rain and not because the government is doing a good job at controlling emissions from vehicles and coal-fired power plants,” Andriyanu of Greenpeace said.

Pulungan of the Jakarta governor’s office insisted that “we are not sitting quietly and doing nothing”. He said that the city administration is hard at work to get people to leave their personal vehicles at home and use buses and trains.

“We are ramping up our public transportation system. We are expanding pavements to encourage more people to walk. We are building bike lanes. We are building facilities for non-motorised transportation,” he said.

Environment ministry director Chaniago said his office is also hard at work to address the problem. Indonesia, he highlighted, is committed to stop building new coal-fired power plants by 2030 and be completely dependent on renewable sources of energy by 2060.

“These things take time. They are not something we can accomplish in a day by saying ‘abracadabra’. But we will get there eventually,” he said.