Inside the elaborate set-up of a scam HQ, staffed by people forced to scam

It is a team of people like these, cloistered in a scam compound, that's often behind one's “random” encounters on social media. (Photo: A Long Chuang Dang Ji)

- Southeast Asia-based syndicates are conning victims worldwide of millions in love-investment scams

- They train in using advanced psychological tactics to win a victim’s trust

- Many scammers are themselves trafficked into the role and tortured

- Agencies and NGOs mount rescues, but syndicate bosses remain out of reach

- Part 1 of a CNA Insider investigative special on love scams

*Names have been changed

SINGAPORE and PHNOM PENH: For some of the people hunched over computers and typing furiously, sweet-talking strangers thousands of miles away, what impels them is the threat of torture — beatings, starvation, even electrocution. For others, it is the prospect of promotion, cash bonuses, or even the promise of drugs.

The spartan room they are in is newly renovated, with rows of office desks. Scores of mobile phones — maybe eight to 10 per person — sit in front of them as they type.

They come from many places, such as China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and as far as Turkey. Singapore, too, is represented. Most of them are men, but there are also several women.

One man is chatting with a woman from Singapore; she thinks he lives there too. She mentions that she is about to go out and asks what he is doing. He immediately does a Google search for “Singapore weather”, then replies: “I slipped in the rain earlier. Be careful.”

Another man mutters to his colleague: “She’s getting upset that I’m bringing up cryptocurrency. How should I respond?” His colleague looks over the conversation unfolding on WhatsApp, then types a reply.

In a smaller room kept separate from everyone else, everything that appears on their screens, whether desktop or phone, is monitored in real time by a “supervisor” whom some have never met. He, or she, reports to yet another person in a shadowy, seemingly endless chain of command.

In another room is the “marketing” department, where some folks put together voice notes, pictures and videos.

One of them is editing a video of a slender young woman cooking fish head curry. It will be sent to an unsuspecting chat partner somewhere in the US or Australia perhaps. Meanwhile, a picture of an empty fridge is sent to one of the men sitting outside who, in turn, forwards it to a woman in Malaysia he’s been chatting up for weeks.

“I just spent the afternoon cleaning my parents’ fridge,” he types. “What were you doing today?”

All this effort goes a long way towards grooming thousands of potential victims around the world. Days if not months are spent gaining their trust and friendship or love — and then scamming them out of millions of dollars in bogus investment schemes or gambling sites.

This is the world of pig-butchering scams, a hybrid of love and investment scams that is gaining traction worldwide.

The non-profit Global Anti-Scam Organisation (Gaso) estimates that it has seen nearly 2,000 victims of these scams since its formation in mid-2021, with a total financial loss of more than US$310 million (S$440 million). These numbers are just the tip of the iceberg, said media spokesperson Grace Yuen, because many victims do not come forward.

Watch: Asia's Tinder Swindlers: Exposing Love Scam Rings In Cambodia (22.41)Pig-butchering scams differ from love scams of old in that they typically involve investment platforms, so that victims do not see it as giving money to a stranger they met online, but rather as investing for their own benefit.

In the Cambodian coastal city of Sihanoukville, gated apartment blocks and casino compounds can house thousands of such scammers.

Each compound, run by well-oiled syndicates, is self-contained, with dormitories, convenience stores and canteens. There may also be barber shops, nightclubs and karaoke lounges on the premises, all catering to employees.

These syndicates operate not just in Cambodia; reports also indicate their presence in Laos and Myanmar, with similarities in what they do and how they work. They are often run like legitimate companies, complete with promotions, bonuses, increments and, yes, marketing departments.

As a Talking Point investigation discovered, the people manning the computers and phones are driven by different things. Some may be there willingly, attracted by the easy money, or fugitives from justice in their own countries.

But others are victims themselves — duped into thinking that they were getting well-paid jobs, and instead trafficked across borders, sold and made compliant through threats of violence or torture.

Based on accounts given by scam victims, former scammers and anti-scam organisations, CNA Insider pieced together an intricate picture of the elaborate inner workings of these syndicates — from what happens in their workrooms, to the secrets of their success, and why, despite the efforts of law enforcement, they still thrive.

Part 2 of this special:

FIRST, ACQUIRING THEIR TARGETS

On Bilce Tan’s first day of work, he was handed lists comprising personal details of people living in Malaysia and Singapore. The information included identification numbers, addresses, bank balances and even their salaries.

The 41-year-old Malaysian had arrived on a flight the day before; he had been promised a business development role and underwent four rounds of interviews before snagging the job offer. But en route to his workplace, three men got into the car he was in — making him, for all intents and purposes, a hostage.

He did not know where the lists came from; he said his supervisor treated him brusquely when he asked. He was told to look at them and identify “key customers” based on their savings, for example, or real estate assets.

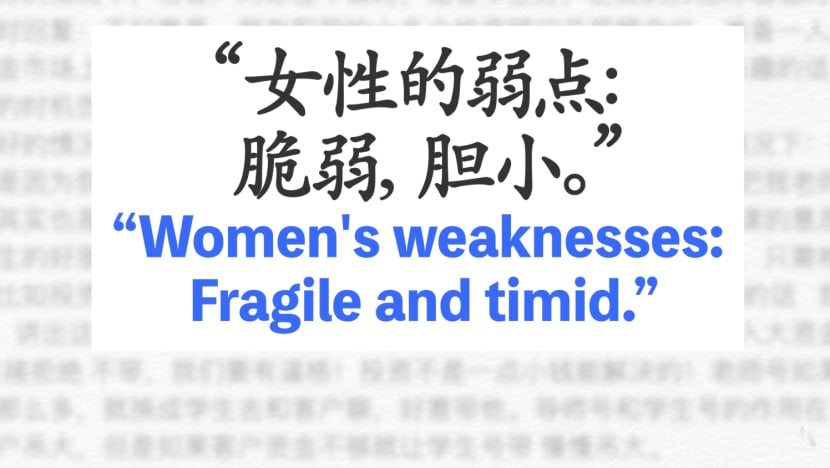

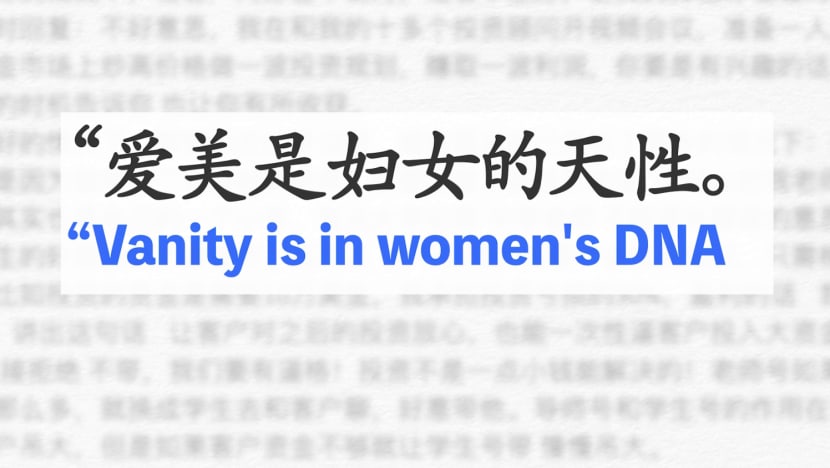

Another former scammer, Lee*, who was in a different syndicate, said women were often targeted because his supervisors believed it was easier to scam women than men.

“Women aren’t as sharp (as men), and their awareness of love scams isn’t as (heightened),” said the Chinese national on what he was told. “Women also might find it harder to extricate themselves from the relationship.”

Lee stressed that he did not concur with this view. And it is clear from other accounts that men are often targeted as well.

In fact, Tan was made to pose as a young woman targeting older men. He was given eight different accounts on various dating sites, all of which he said were created by the marketing department in his compound.

Lee, meanwhile, was told to trawl for images of good-looking people on social media sites, like Facebook and China-based platform Xiaohongshu. These were used to create fake profiles with which they then hunted for potential victims on social media and through dating apps.

MOVING IN FOR THE KILL

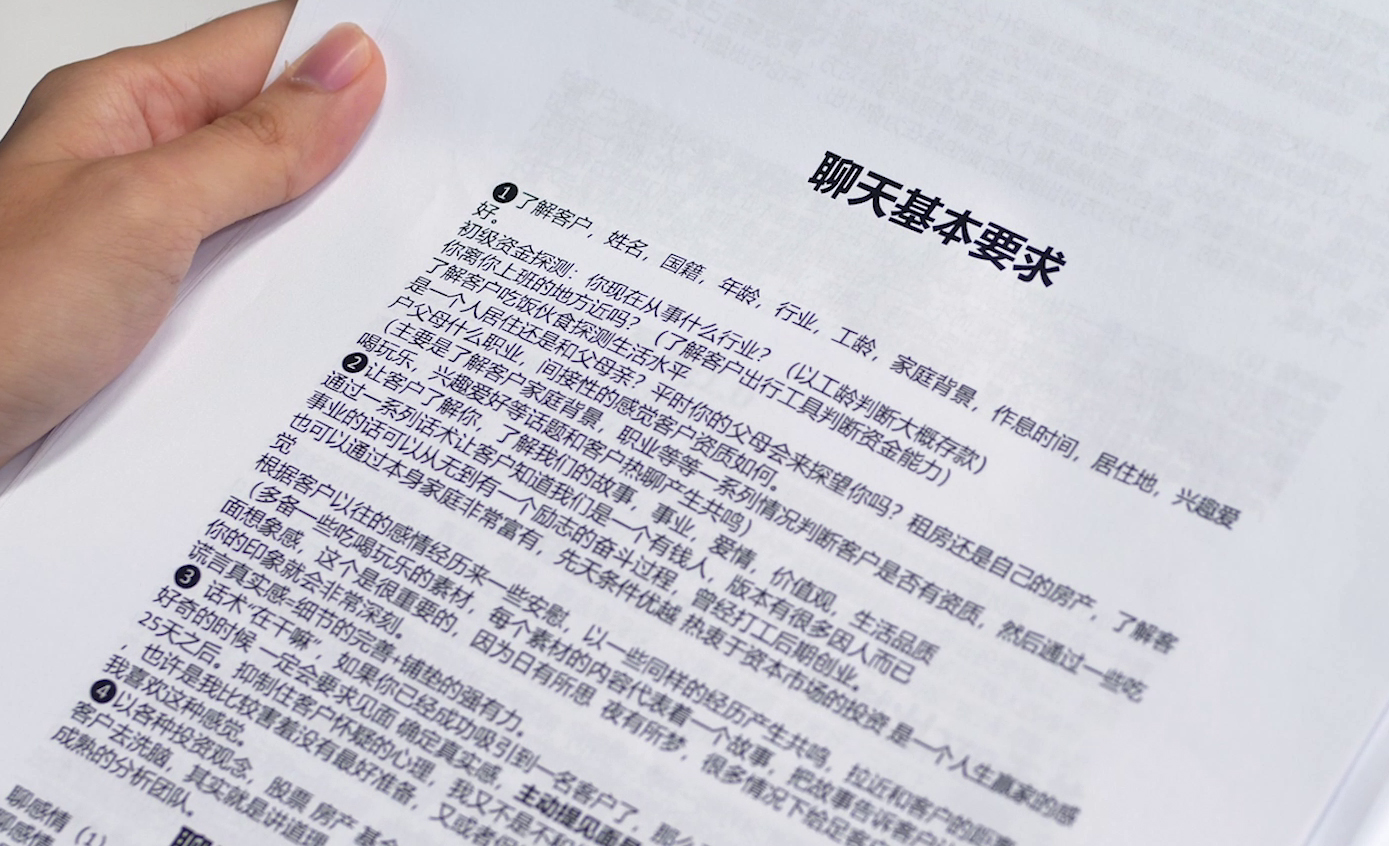

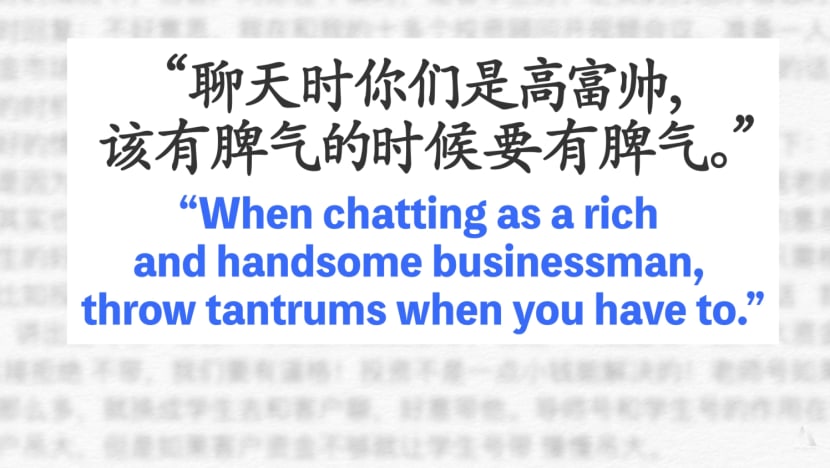

The scammers are armed with a set of workbooks with instructions on how to groom their victims. CNA Insider obtained these workbooks from various anti-scam organisations, including the International Anti-Scam & Trafficking Alliance.

On the first day of interaction, for example, the workbooks instruct them to focus mainly on chatting. “It’s important to let the woman feel our sincerity and that we’re authentic,” the workbooks said.

Unconventional introductions that stand out — such as starting with a nugget of information gleaned from a target’s profile — can be used to good effect.

One Singaporean victim, Kelly*, remembers how she was approached on Instagram. “You look like you’re a foodie,” wrote the man, who went on to ask her whether she cooked and where she liked to buy food.

“I think he looked through my profile beforehand,” she said. “He seemed like someone who was very interested in the things I did.”

Her interest piqued, she responded to him. In the end, she lost almost S$40,000 in two scams.

After the opening gambit

A scammer is instructed how to assess if a victim is worth scamming — extracted from ‘The Fundamentals of Chatting’ from a scam manual.

Questions to ask to discern a customer’s financial status

- What industry are you in now? (Estimate their savings based on the number of years they have worked)

- Do you live near your office? (Gauge their financial status from their preferred travelling method)

- Find out where they enjoy eating and what they eat, to understand their quality of life.

Let the customer know you are wealthy. You can:

- make up a story of how you have struggled in part-time jobs and finally set up your own company.

- portray yourself as coming from a very wealthy family, with lots of advantages in different kinds of investments. You are born to be a winner.

- listen to your customer’s love histories and mirror them by sharing similar past experiences to create an intimate bond with them.

The workbooks also suggest what to do if there is difficulty continuing a conversation: “Make use of Baidu (a search engine) to extend the conversation. When talking about tourism, immediately search for the location and famous tourist spots that the other party is talking about to engage them.”

Very likely this is what happened to Malaysian scam victim Samantha*. The man she was chatting to online represented himself as a Shanghainese and could go into details about the various tourist attractions and streets he said he would take her to see. “It was just so real,” she recalled.

In the end, she lost about US$20,000 to him.

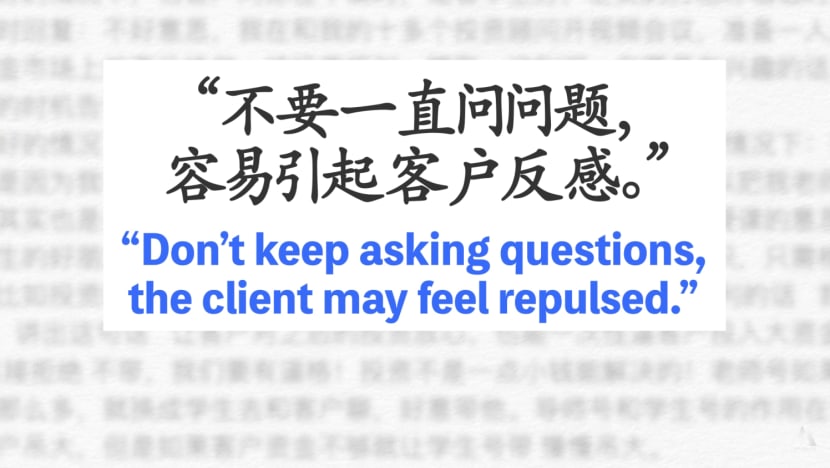

“Don’t be nosy and probe directly (for personal information),” one workbook warned. For example, should the scammers want to find out how much money a victim has, they could ask: “How far is your office from your home?”

If a victim responds that he or she drives to work, for instance, they can deduce that the victim is affluent enough to afford a car.

They should also subtly portray themselves as “mature”, “successful” and, above all, human. “Have an engaging conversation … then stop, because (for) a successful person, it’s impossible to hold a mobile phone and chat with people all day,” one workbook cautioned.

It is all right to have an argument with victims — say, if they are spending too much time with members of the opposite sex, or are working too hard and neglecting their health — because that makes the relationship seem real.

Listen: A scammer comes across as caring for his victim. (Source: Gaso)

A translation of the conversation in Mandarin between a scammer and his victim, a nurse. (Recorded by a scam-baiter with the Global Anti-Scam Organisation)

Scammer: I’m finally hearing my wifey’s voice. Wifey, why are you rushing to go back to work? You should rest for two more days.

Victim: I just happened to have an operation.

Scammer: Even though you have an operation, you shouldn’t have to rush there this afternoon. How is your situation now, is your boss not aware of it?

Victim: He knows.

Scammer: If your boss recalls you, he really wants your life. If he calls you to come back in this situation, is he being humane? I’m asking you. Wifey, even though it’s only half a day, I hope that you will only return to work after you have fully recovered, OK?

Look at yourself, initially you were recovering pretty well. After you went out for an afternoon, now you’ve come back in this state.

Besides notes on how to approach victims, there are primers on cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and USDT. There are also suggestions on how to respond if the other party does not seem interested, and how to begin bringing up the subject of investing or buying cryptocurrency.

The man Kelly was speaking to did not raise the subject during the two months he spent cultivating her. And when she showed disinterest the first time he did, he dropped it.

Over that period, he showered her with care and even spoke to her teenage children when she had some issues with them. “I think he was just more patient,” she said.

Watch: How To Tell If You're Being Scammed: Love Scammers' Tactics Exposed (13.20)

While the workbooks point to the lengths to which scammers can go to groom their victims before they move in for the kill, their scamming expertise went beyond the workbooks.

According to Chan*, a Chinese national trapped in a syndicate in Laos for two months, among its managers was a psychology graduate. “He provided high-level analysis of victims’ investment behaviours,” he said. “There were a lot of experts like this.”

While chatting to victims — referred to as “clients” — the scammers also work in teams. There were four in Lee’s team. “If we face questions from clients we don’t know how to answer, we’d consult one another,” he said.

“If we really can’t understand, then we’d ask our supervisors.”

Are you a victim of a scam, or think a loved one is? Here’s where you can get help:

For help wherever you are, contact the Global Anti-Scam Organisation or the Global Anti-Scam Alliance.

If you're in Singapore, call the anti-scam hotline 1800 722 6688 or go to www.scamalert.sg for scam-related advice. To provide information on scams, call the police hotline 1800 255 0000, or submit online at www.police.gov.sg/iwitness.

Share with us your story at cnainsider [at] mediacorp.com.sg (cnainsider[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg)INCENTIVES GIVEN, BUT MAIN MOTIVATION IS FEAR

It was not easy for Lee, who describes himself as someone who “doesn’t talk much”, to become an online Casanova. He went through more than a week of training with three to five trainers before he began interacting with clients.

He said the most important part is understanding the victims’ basic information, their interests and their emotional needs. “There’s always a desire in everyone’s heart,” he said. “If we know what they desire, we can give them the satisfaction.”

In the end, he memorised the scripts. He said there were times when he was tested on the spot, and if he could not recall the facts, he would be scolded and made to do squats or push-ups.

Make mistakes multiple times, and the punishment could be an electric shock. In the scam compounds, beatings and even torture were commonplace, as a way of ensuring compliance, he observed.

Conditions there can vary, according to Jacob Sims, director of International Justice Mission (IJM) Cambodia, a non-governmental organisation helping to rescue scammers who are trapped in these compounds.

“Maybe they aren’t allowed to leave … they’ve had their passports taken, but they’re given adequate food and pay,” he cited. Then there are people who have been “physically abused, tasered (or) had food, water and sleep withheld, (along with) their pay”.

In Chan’s syndicate, scammers had three months to show results in the form of a successful scam. Only then were they paid a salary, he said.

“If you don’t even manage to scam a single person … you may be beaten or sold to other companies.”

Another ex-scammer told CNA they had to work until late at night and would be beaten and tasered if they could not cheat at least one person every week. The 32-year-old Malaysian said anybody who wanted to be released had to pay RM50,000 (S$15,000).

But there is a flip side. “There are reports of people being given rewards,” said Sims, citing witness testimonies his organisation has received. “Maybe a bigger room or … drugs.”

Prostitutes are also offered as an incentive besides money. And according to International Anti-Scam and Trafficking Alliance documents, a scam employee’s commission can range from 5 to 15 per cent. But it is likely that those who are there willingly are by far in the minority, Sims added.

All the former scammers CNA Insider spoke to said they did not succeed in scamming anyone.

Tan, who was trapped in a scam compound for three weeks and worked 15-hour shifts, recalled chatting up and befriending a Malaysian widower who was on the verge of making an investment.

But when the time came to “close the deal”, he could not bring himself to do it, choosing instead to “play dumb” whenever his supervisor asked him about it.

“Maybe I might’ve got a pay raise or promotion, but at the cost of causing an entire family to fall apart,” said Tan, referring to the man’s ailing mother and dependent children.

ONE OF MANY

In the short time Tan was in the compound, he realised he was just one of many. He slept in a dormitory with three others in his room. And meals were taken in a canteen that could hold up to a few thousand people at any one time, he reckoned.

It was during canteen time that he tried to find out more about the place. He made a point of sitting with different people and eavesdropping on others’ conversations, he said.

He assessed that most people there were from China, but there were also Indonesians, Filipinos, Malaysians and even Singaporeans.

Many of them were like him — trapped — he deduced, while those who were willingly there included criminals who had fled their respective countries.

According to Gaso, most of the victims are young men in their 20s. Around 80 per cent are from rural China, while Malaysians and Taiwanese make up a substantial minority. Among the Taiwanese, almost all have a university degree.

As scam syndicates try to target English speakers, Gaso has recently noticed non-Chinese speakers from South Asia and Africa and even Ukrainians among the victims.

According to Taiwan’s National Police Agency, the likely number of Taiwanese trafficking victims who are currently in Cambodia against their will is around 2,000 as reported in August, though it could be as high as 5,000.

The Malaysian police, meanwhile, said last month that they had received 224 reports from family members and friends of missing Malaysians since last year. These involved 284 job scam victims, of whom 110 had been rescued.

But a Harian Metro report this month, based on complaints and information provided by NGOs, estimated that 3,000 Malaysians are stranded abroad.

In Singapore, there has been one police report made since last year. The complainant claimed that there were Singaporean victims in Myanmar possibly being kept against their will by scam syndicates, Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam told Parliament in a written response last month.

On Oct 3, in another written Parliamentary reply, he said Singapore participates in various regional efforts to discuss cooperation on combating transnational crime, including scams and trafficking in persons.

This includes the Asean Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime and its working group on trafficking in persons, as well as the Asean Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime.

Gaso, which also plays a role in rescuing trafficked scammers, said that while these job scams initially targeted Chinese nationals, syndicates have changed their tactics because of an increasing awareness of these scams in China.

Tan suggested another possible reason. “Many of them aren’t fluent in English or Malay, which reduces the market (in) Malaysia and Indonesia,” he said.

“Singaporeans and Malaysians are proficient in more languages. Besides, we’re much more obedient compared to people from China.”

In Chan’s case, a friend had invited him to apply for what was touted as a sales job to find customers for a casino. Chan, who was working in Shanghai, travelled to Yunan and was then snuck into Laos by a syndicate.

He later learnt that those who were trapped were encouraged by syndicates to lure their friends into the job. “Once they scam a certain number of people (into coming) over, they can go back,” he said.

Gaso spokesperson Yuen also highlighted several “crazy stories” told to its rescue team. For instance, people have been snatched from the streets and sold to syndicates.

This happened to Lee. Last November, he resigned from his job in a Chinese restaurant in Sihanoukville. He left with his luggage and passport and was walking alongside the road when a black van pulled up and two men bundled him into the back.

“When I was in the scam syndicate, I saw families breaking up and people killing themselves as a result of these scams,” he said. “I thought of committing suicide.”

SHADOWY BOSSES

Sihanoukville is a five-hour drive from Phnom Penh and is known for its beaches. But reports have described the city as rife with Chinese criminal networks and as a breeding ground for pig-butchering syndicates.

A drive in the area around the city’s Chinatown showed the Talking Point team several apartment complexes that looked empty from the outside but were heavily guarded. As vans went in and out, the security guards did checks.

A peek inside, through the security grilles, revealed restaurants, clinics and barber shops. According to local media outlets, these condominium compounds can hold tens of thousands of people.

But why did syndicates choose Sihanoukville as their base?

Political analyst and activist Ou Virak, who has been monitoring the development of scam activities in Sihanoukville over the past few years, pointed to the city’s strategic location and deep port for trade.

“A lot of legitimate investments come to Sihanoukville,” said Ou, who cited infrastructure projects in particular, such as expressways. Most of these investments come from China, he noted. But with legitimate investments came a crime wave.

“There was a period when Cambodia was pretty much open for business … open for anything, including online gambling and casinos,” he said.

“And we’re starting to see that in a city that’s growing so rapidly, casinos are becoming fronts for anything that’s happening, whether it’s money laundering or various types of scams.”

Lee described being at the bottom of a hierarchical structure involving members like himself, small group leaders, big group leaders and supervisors. He also mentioned departments like customer service and human resources. Then there is the little boss and the big boss, who remains a shadowy figure behind the scenes.

“The (big) boss won’t let us know who he is or what he looks like,” said Lee. “He doesn’t interact with low-level members … only the little boss. Then the little boss will take charge.”

With so many people involved in the syndicates, it can be a challenge catching the big fish. Gaso’s Yuen said that because these scam compounds bring in money for local communities, local governments can sometimes turn a blind eye.

“All the people in the scam compound need to be fed and entertained. It’s a large amount of money keeping local people employed in some way.”

Besides, she added, “they’re not scamming the (locals)”.

The United States government recently downgraded Cambodia to Tier 3, the lowest tier, in its 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report released in July, citing “a lack of significant effort” as well as “endemic corruption” as an impediment to law enforcement operations, holding traffickers accountable and victim service provision.

“Authorities did not investigate or hold criminally accountable any officials involved in the large majority of credible reports of complicity,” the report stated, highlighting online scam operations as an example.

Nonetheless, Ou felt that Cambodian authorities have been taking “more effort” to clean up Sihanoukville’s image. The government has been placed under pressure, he said, because photos and videos of the crimes have started to surface online.

But the crackdowns are “too few and far between”, and success has been “minimal”, he added. “It’s still the wild South in a way.”

Indeed while filming there, the Talking Point crew had some safety concerns.

In a response in June to Talking Point’s queries, deputy governor of Preah Sihanouk province, Long Dimanche, said all cases reported by victims, including scams, are thoroughly investigated by the province’s police commissariat with complete confidentiality.

He added that the police are unable to act, however, if such crimes go unreported or are lacking in evidence.

“The Cambodian government has been paying very close attention to building new infrastructure and reinforcing public order, especially public or national security,” he said, highlighting this as an area it has “prioritised the most” because “development goes hand in hand with security, peace and stability”.

He appealed to all stakeholders, including investors and residents, to obey Cambodian laws.

A ‘DAVID AND GOLIATH’ SITUATION

It would seem the task of taking down these syndicates is a herculean one. But organisations on the ground are doing what they can.

“When we receive a complaint or referral, we provide an intervention request to the government, and then we coordinate between the police and the embassy to try to motivate and facilitate a rescue,” said Sims from IJM Cambodia.

His organisation receives referrals from other NGOs that trafficked scammers have reached out to, while one scammer even reached out to him at his personal Twitter account.

There are times when the families of trafficked scammers contact Gaso as well, said Yuen. That is when it works with embassies, law enforcement and other NGOs to get those scammers out from their compound, provide safe houses for them and eventually get them out of the country.

Since its inception in July last year, Gaso has been involved in the rescue of 172 victims from scam compounds. It has also worked with Taiwanese law enforcement on a fraud case, resulting in a raid on a gang in Taiwan.

And the organisation has partnered with Taiwanese YouTuber Bump, who accompanied a Gaso team to Cambodia to participate in a rescue.

Bump, who later produced a video detailing his experience, had got involved when a victim’s family approached him for help in rescuing their son who was trapped in a scam compound in Cambodia’s Koh Kong province.

The challenges they faced included trying to report the case to the local police, the YouTuber told CNA Insider.

After they made the report, they were requested to hold their passports up while the police took photos of them, the victim’s father included.

“We thought it was a bit strange,” said Bump. “But we didn’t think too much because (the police officer) seemed very … empathetic.”

He found out a few hours later that their photos had been sent to the scam compound. They got word of this from the victim, who had stolen a phone. Nonetheless, father and son were reunited a day later.

“It’s a David and Goliath situation,” said Yuen. “But we try to do the best we can.”

CNA Insider has reached out to the Koh Kong provincial administration for a response. There are other efforts, meanwhile, by various governments to prevent people from falling victim to such job scams.

Taiwan has formed an inter-ministerial task force to rescue Taiwanese trapped in Cambodia and to prevent others from being duped, according to news reports. There are also signs at the airports warning people of possible job scams.

Hong Kong has a task force doing the same, while Malaysia recently also set up a committee to tackle the issue.

Malaysian ambassador to Cambodia, Eldeen Husaini Mohd Hashim, told the Bernama news agency in July that the country is working with relevant Cambodian authorities to help stranded Malaysians return home, but “the process in handling the cases differs and takes time”.

CNA Insider has reached out to Interpol about the work being doing and obstacles in the way.

Some of the challenges are already apparent. Thai authorities announced plans in March to rescue up to 3,000 Thai nationals from scam compounds in Cambodia, but only 66 were rescued successfully. Independent Cambodian news agency VOD, citing Thai police, reported that some rescues were botched after scam bosses found out about the raids.

For the ones who have made it back to safety, it is about picking up the pieces.

Tan was able to return to Malaysia, escaping with help from someone he refers to as his “angel”. But his ordeal is not over: Since going public with his story, he has been sued for defamation by a person from the company that had offered him employment in Cambodia.

CNA Insider contacted the plaintiff’s lawyers for comment, and they replied that they were unable to disclose any information concerning ongoing court proceedings.

His legal struggle notwithstanding, Tan knows he had a lucky escape. There were times, he said, when he thought he would die in the scam compound.

Another Malaysian, a 23-year-old victim of a syndicate in Myanmar, died of abuse in May. And for each escapee, there are many others still trapped within the walls of these compounds.

Additional reporting by Jinee Chen

This is the first in a two-part special report on global pig-butchering scams by Southeast Asia-based syndicates. Next up, the unlikely victims these scam syndicates claim.

Watch the Talking Point episode here.