Malaysia has become less friendly to Myanmar refugees. What hope for them now?

There are some 183,000 refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia, mostly from Myanmar. But xenophobic sentiments have increased — as have deportations, despite official opposition to Myanmar’s military takeover. The programme Insight explores the plight of those fleeing conflict.

A Myanmar national swept up in a raid in Malaysia.

KUALA LUMPUR: She had no safe place to run to after the Myanmar military seized power from Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected civilian government in 2021.

Afraid to remain in her home in Chin state, one of Myanmar’s poorest, Zin May Htoo fled to the mountains. But without food, survival became impossible. The military “intentionally blocked all the (supply) channels to starve us,” said the 28-year-old.

To escape armed conflict, she made the journey to Malaysia through Thailand last year. It took her over a week, but she arrived safely and settled in Pudu, a neighbourhood in Kuala Lumpur with a sizeable community of her countrymen.

Like her, former military clerk John (not his real name) fled to Malaysia for safety. He had been serving with an infantry battalion in Rakhine state but “couldn’t bear to see members of the public being killed”, so he deserted.

This meant he had broken military law and become part of the civil disobedience movement, he said. Should he be prosecuted in his home country, the military would “make up charges as they please under the pretence of law”.

“Civil servants who take part in the civil disobedience movement will be prosecuted on serious charges, like treason and insurrection,” he added.

Since the coup in February 2021, more than 2,960 civilians have been killed in Myanmar through crackdowns following pro-democracy movements — with more than 13,850 people under detention as at Feb 8 — according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

Refuge in Malaysia is crucial for people like May Htoo and John, but their situation has become more precarious as Malaysia steps up its deportation of asylum seekers.

Between last April and October, over 2,000 Myanmar nationals including military defectors were returned without assessment of their asylum claims or other protection needs, said non-governmental organisation Human Rights Watch.

Malaysian authorities have “accelerated the number of asylum seekers summarily deported to Myanmar”, it added.

On the ground, it means community leaders such as Kam Lian Mang, a pastor who provides pastoral care for over 200 Myanmar migrants, have seen more people in recent months seeking help in locating their loved ones in detention.

He showed the programme Insight a list of 53 people he has determined are in jail. To locate them before they are repatriated is an arduous process. Some are still uncontactable, he said.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), also known as the UN Refugee Agency, has expressed concern about the deportations.

It called for an immediate stop to the forced returns, urging Malaysian authorities to “abide by their international legal obligations and ensure the full respect for the rights of people in need of international protection”.

STILL ‘MORE RESPECTFUL’ OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Like many Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol. Malaysian law does not distinguish between refugees and undocumented migrants.

Even so, the UN Refugee Agency said international law prohibits states from returning individuals to a country where they face a real risk of persecution or other human rights violations.

And compared to its neighbouring countries, Malaysia is “more respectful” of human rights, said James Bawi Thang Bik, a consultant to the Paletwa Khumi Community in Malaysia. (Paletwa is a township in Chin state; the Khumi are a tribe there.)

There are some 183,000 refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia, of whom 86 per cent are from Myanmar.

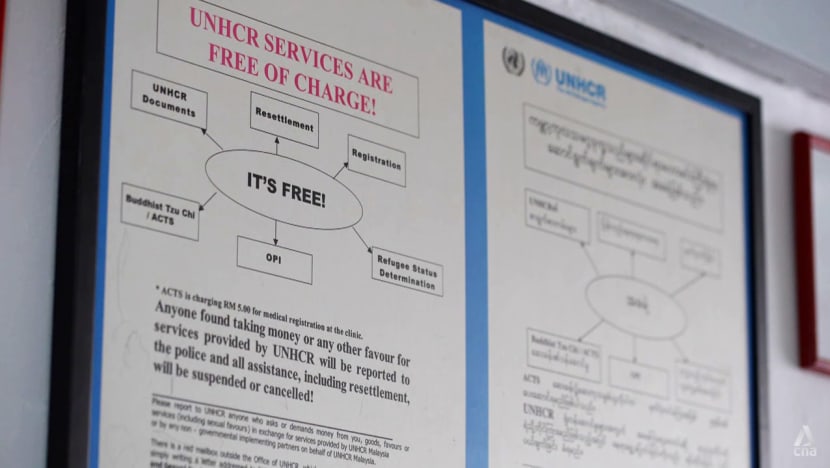

Asylum seekers may be issued a UNHCR card — which has “no formal legal value” in Malaysia but “may reduce the risk of arrest and allow limited access to health services, education and other essential support services”, the agency stated on its website.

Bawi has relied on this “level of protection” since 2013. He arrived in Malaysia as a 16-year-old in 2010 after sneaking out of an orphanage in Chin state to be smuggled out of Myanmar by a human trafficker.

“When I recall my past, I’m so shocked at how I was so brave,” he said with a wry chuckle. “I’d never met the agent, and I didn’t know him.”

His mother, who was already in Malaysia, was the one who paid for him to escape violence against minorities in their home country.

“When I met my mum, it was very emotional,” he said. “I didn’t believe that this was my biological mum and that I was going to have the chance to live with (her).”

A critic of Myanmar’s government, he was shaken by news in February 2021 that over 1,000 of his countrymen were deported from Malaysia despite a court order temporarily halting their repatriation. The deportees were picked up by Myanmar navy ships.

This came at a time when access to detainees had become increasingly difficult. The UN Refugee Agency, which is allowed to operate in Malaysia, has not received approval from immigration authorities to access detention centres since August 2019.

RISE IN XENOPHOBIC SENTIMENTS

Deportations have since continued and have followed in the wake of heightened anti-immigrant sentiments during the pandemic, observers noted.

“It’s very clear that (in) the last two to three years, we’ve seen … more xenophobic sentiments,” said Tricia Yeoh, chief executive officer of the think-tank, Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs.

“I can’t say whether this is exclusive to Malaysia, but it’s clear, when there’s some kind of security threat, local communities feel that … scarce resources need to be allocated more exclusively for local communities as opposed to … foreign communities.”

When COVID-19 hit Malaysia, a rumour “went around” that Rohingyas were among a group who went to a mosque in Klang Valley and got infected, recalled Malaysia’s former foreign minister Saifuddin Abdullah.

Raids have also been stepped up since the pandemic. Analysts said another reason could be domestic politics, especially leading up to Malaysia’s general election last November.

“The last few years have also coincided with our own Malaysian domestic political landscape (having) been fluctuating,” said Yeoh. “Because of this, it’s been very easy, I think, to channel these energies towards a common external threat, real or imagined.”

Two months prior to the elections, the National Security Council even proposed closing the UNHCR office and taking over duties such as registering refugees.

To Bawi’s knowledge, “this kind of thing has never happened before”, as the UNHCR is a “life source” for refugees. Talk of shutting it down is evidence of the government being “aggressive towards refugees”, he said.

OPPOSITION TO COUP CALLED INTO QUESTION

The repatriations fly in the face of Malaysia’s opposition to the takeover of Myanmar by its military.

Saifuddin was a key figure in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (Asean’s) five-point consensus — towards which little progress has been made — on the need for an immediate end to violence, dialogue among all parties and other steps towards peace.

He has also engaged with the National Unity Government, Myanmar’s shadow administration. And he said Malaysia’s foreign ministry has not changed its approach in “looking at ways” to “attend to whoever (comes) to our shores”.

WATCH: Why are Myanmar refugees in Malaysia being deported, even at the risk of death? (44:56)

“Of course, there are other factors that are beyond our control and, in particular, beyond our ministry,” he acknowledged. “There are certain laws that we have to abide (by): There are the immigration laws, there are other rules and regulations.”

Malaysian politician Charles Santiago noted the difference between the foreign and home affairs ministries — and their respective motivations.

“There must be a transfer of information, thinking and some kind of understanding that has to prevail,” added Santiago of the Democratic Action Party, a Pakatan Harapan component party.

At the regional level, “there’s no political will” to restore democracy in Myanmar as Asean is divided on the issue, he reckoned.

For instance, Thailand, which shares a 2,400-kilometre border with Myanmar, continues to engage with the junta and hesitates to speak out against the atrocities committed since it seized power.

Experts point to the two countries’ shared geopolitical interests as well as Thailand’s dependence on Myanmar for labour and energy.

ALL EYES ON NEW GOVERNMENT

In Malaysia, with a new Cabinet led by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, it remains to be seen whether the pace of raids and deportations will keep up.

Days after the swearing-in ceremony in December, the courts lifted a stay of deportation that had been granted to 114 Myanmar nationals and dismissed two NGOs’ application for a fresh stay.

It is also not known whether the new government will continue the Tracking Refugees Information System (Tris) to gather information on refugees and asylum seekers.

According to Tris’ website, the system allows the government to easily verify identities using a national database, minimising the risk of individuals being arrested and detained. But some migrants worry about handing over their information.

Last September, the then Home Minister, Hamzah Zainudin, said people who are registered could also benefit from job opportunities and training.

Saifuddin agreed that allowing refugees to work would show Malaysia to be “really humanitarian in our approach” and augment its workforce. He also hopes Malaysia will re-impose a moratorium on the repatriation of Myanmar nationals.

Yeoh’s think-tank had estimated in 2019 that refugees would contribute as much as RM5 billion (S$1.54 billion) to Malaysia’s gross domestic product if they were granted the right to work.

“The Prime Minister should step in and bring about some kind of co-ordination. … (His) commitment to human rights has to (count) for something,” said Santiago, the chairperson of Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights.

As the new government finds its feet, refugees like Bawi also hold out hope for change. Currently pursuing a law degree, he said the deportations are “not really appropriate”.

“It isn’t the right time for refugees to be deported back to Myanmar, because we all know about the situation (after the coup).”

What he ultimately wants, however, is a stable, peaceful Myanmar. “I want to see my people as tourists (in Malaysia), not as refugees,” he added.

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.