Inside SCDF’s emergency ambulance services: When minutes can mean life or death

They respond to various 995 calls and are always in a race against time to save lives. But non-emergencies can take precious resources away from critical patients who rely on SCDF responders, depriving them of an earlier ambulance response.

CNA Insider gets unprecedented access to the Singapore Civil Defence Force’s medical emergency services team.

In partnership with the Singapore Civil Defence Force

SINGAPORE: The 995 call came in on a Monday morning. An epileptic patient at a residential care home had gone into convulsions.

Within 15 minutes of being assigned to the case, the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF) ambulance crew from Central Fire Station were by the patient’s side and checking his vital signs. It was a Priority 1+ emergency — the most time-sensitive and highest level of urgency.

As paramedic Sergeant 2 (SGT2) Andrea Ang called out to the patient and checked his eyes, he moaned. He was having another fit. The ambulance crew quickly turned him onto his side for Ang to administer the emergency drug diazepam.

But the first dose did not stop the seizure.

“That’s when we knew that it was very important to rush him to the hospital as soon as possible,” recounted Ang. “Because if we didn’t stop the seizure, he may have eventually stopped breathing or gone into cardiac arrest.”

In the ambulance, she hooked the patient up to a pulse oximeter to monitor his blood oxygen level – then had to dispense more diazepam as he suffered another epileptic seizure. Without such interventions, continuous fits may lead to permanent brain damage or death.

She also took a moment to pat the distressed man on the shoulder, assuring him: “We go to the hospital, okay?”

Ang keyed the man’s vital signs and other critical medical information into a tablet. These were instantly fed to the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) where emergency medical staff — alerted by SCDF’s operations centre — prepared a resuscitation room ahead of the patient’s arrival.

SGH consultant in emergency medicine Joanna Chan noted the timeliness of the ambulance crew’s intervention and updates on the patient.

“This helps us to decide what to do next: whether we can give the next dose of medication immediately or delay it for a while to make sure that we don’t cause treatment side-effects,” she said.

This was just one of the 670 medical emergency calls a day that are made to the 995 line.

And each time, a well-oiled emergency response system kicks into action — from dozens of call-takers and ambulance despatchers at the SCDF operations centre, to ambulance crews at fire stations and fire posts around the island, and the medical teams at hospital emergency wards.

In many cases, such as trauma, strokes and heart attacks, minutes can make the difference between life and death, between an eventual full recovery and a futile one.

But some calls — 46 a day, on average — turn out to be non-emergencies or false alarms. Last year, there were a total of 17,009 such calls.

Tending to such cases can come at a cost to a patient in a genuine crisis.

“Consider a scenario where an individual who experiences wrist pain calls 995. This takes vital resources away from life-threatening emergencies such as a cardiac arrest,” said Colonel (COL) Hong Dehan, SCDF’s chief medical officer.

WATCH: On call with Singapore’s emergency medical services — When minutes can mean life or death (20:27)

SCDF’S EYES AND EARS

The nerve centre of this emergency response system sits in an underground facility in the heart of Ubi, at SCDF headquarters.

The lines are manned 24-7 by staff working 12-hour shifts; they include nurses, civilians and full-time national servicemen. They work alongside ambulance despatchers and monitoring officers who liaise with the ambulance crews and hospitals.

The staff have eyes on the fire stations through the closed-circuit television cameras; and on expressways and road conditions, displayed on a bank of screens in the front of the room.

The call-takers, seated in front of curved computer monitors showing details of each case, answer each call in calm, measured tones.

One instructed a caller whose father was unconscious: “I need you to put your hand on his stomach and feel whether there’s any rise and fall.”

On another line, a frantic caller sobbed: “There’s an uncle, my neighbour, he’s not moving. I don’t know what to do.” The call-taker calmed her down and asked for details.

Each call-taker asks a methodical series of questions, with the caller’s replies entered into the computer network. An Advanced Medical Protocol System helps triage the cases according to the level of urgency.

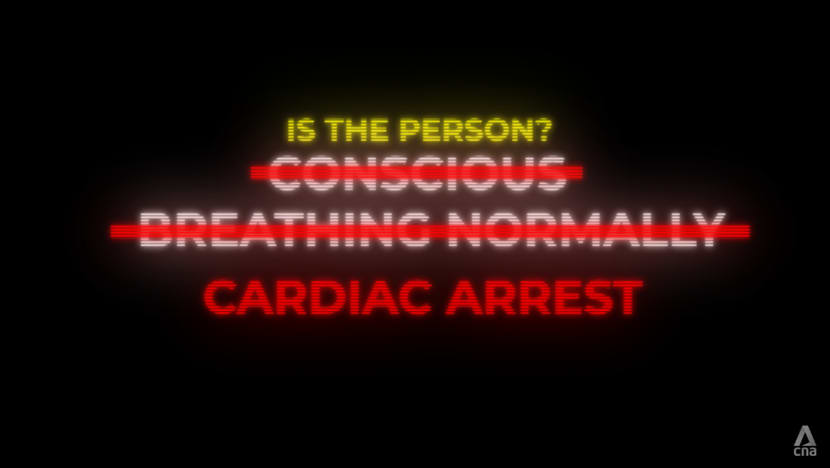

“The most urgent questions that we ask right at the beginning of most calls is whether the person is conscious (and) is breathing normally,” said National University Hospital senior consultant Benjamin Leong, a member of the SCDF’s medical advisory committee.

“If they’re not conscious and not breathing, that would identify cardiac arrest, and I’d immediately despatch the ambulance.”

In such cases, while the ambulance is en route, the call-taker guides the caller through the steps of administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It is critical to keep blood flowing to the brain.

An alert is also sent out to community first-responders through the myResponder app.

“Every minute that nothing’s done, the chance of survival actually drops by 10 per cent,” said Warrant Officer 2 (WO2) Kenneth Foong, an advanced paramedic from Marina Bay Fire Station.

Operations centre personnel are aided by an emergency video system, rolled out by SCDF and the Singapore Police Force last year to enable a live-view of the scene — such as at fires and accidents — through the caller’s phone.

In the case of medical emergencies, the nurses on duty at the operations centre can, for instance, use it to assess whether an unconscious patient might be in cardiac arrest, or to guide callers.

“Turn him onto his right side so (that) his breathing is easier,” senior staff nurse Geraldine Goh instructed a caller, watching as they put the patient in a recovery position.

COLD DINNERS, FREQUENT CALLERS

Over at the fire stations, each ambulance crew typically responds to five to seven calls over a 12-hour shift. The day shift starts at 8 a.m. and the night shift at 8 p.m.

The day shift typically sees more medical emergency cases, ranging from seizures to chest pains to road accidents. The weekends, including Fridays and eves of public holidays, bring more cases at public entertainment outlets — often involving intoxicated revellers or fights.

The crews do not only treat and convey patients, but also are in communication with the operations centre and the hospital while on the move, feeding information to the hospitals’ Emergency Department via the Electronic Patient Management System. At the hospital, they ensure a smooth transition of patient care to the emergency physicians or even help reassure patients if need be.

Some days, there is little respite from this whirlwind of activity.

Returning to Central Fire Station after attending to one call, advanced paramedic SGT3 Muhammad Zuhaili had barely time to put down a takeaway bag of dinner when a new call came in — and his crew headed out again.

Interrupted meals are not uncommon for emergency responders; they sometimes return to cold dinners or lunches, or missed meals altogether. But this time, the caller was someone familiar.

It was a 40-year-old man who had dialled 995 many times in recent months with similar medical complaints about “suffocating” and breathing difficulties. Just recently, he had rung for an ambulance three days in a row.

As they set out, Zuhaili called the man to check in with him. “I feel breathless,” the man said. Because breathing difficulties are typically triaged as P1+ cases, the ambulance crew decided to beat a red light, with sirens blaring.

Zuhaili does not take these calls lightly — no matter the caller. “When we go to the scene, we don’t judge, we don’t form assumptions immediately. We make our checks, and then we come to a diagnosis,” he said.

Zuhaili examined the man and assessed that the matter was not life-threatening. But as the patient had complained of chest pain, he was conveyed to hospital, where he was triaged as a P2 or moderate emergency.

Explaining how chest pain can cover a wide spectrum of conditions, SGH senior consultant and clinician scientist Marcus Ong, who is also a member of the SCDF’s medical advisory committee, said: “You can have something as serious as a heart attack, but 80 to 90 per cent of patients aren’t having one. They could be having, for example, musculoskeletal pain (or) heart burn.”

In such cases it may be better to play it safe — but other calls are more obviously of a non-emergency nature.

SCDF’S NON-CONVEYANCE POLICY

Some people may call 995 even when they have a toothache, according to COL Dennis Quah, commander of the SCDF’s operations centre.

Other minor complaints have included an elderly man who had calf pain and did not want to walk to the clinic; and a caller who cut her finger on broken glass.

Last year, SCDF ambulances responded to 6,285 false alarm calls. The biggest group of callers for minor emergencies (P3) and non-emergencies (P4) are aged 30 to 49. Callers 29 and under make up a third of P4 cases.

One caller felt dizzy after being in the sun. As his blood sugar and blood pressure were normal, the paramedic who checked him filled in a treat-and-discharged form that he could take to a polyclinic if he felt unwell again.

“When our paramedics arrive at the scene, and they assess the patient and deem that it’s a non-emergency, they won’t convey (the patient) to the nearest hospital,” said Quah.

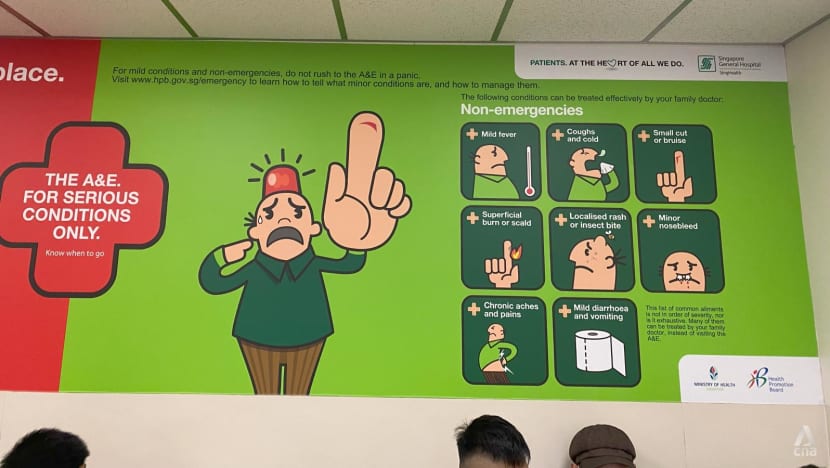

What counts as an emergency?

The list includes: Traffic and worksite accidents, uncontrollable bleeding, broken bones, sudden severe chest pain or breathlessness, drug overdose or poisoning, choking with difficulty in breathing, sudden abdominal pain that doesn’t subside, loss of consciousness, and head injuries with bleeding, drowsiness or vomiting.

Non-emergency cases include: Mild fever, coughs and colds, small bruises or cuts, localised rash or insect bites, chronic aches, superficial burns, and mild diarrhoea or vomiting.

Besides seeing a GP or polyclinic, non-emergency patients can access telemedicine providers or go to an urgent care centre, like the one at Admiralty operated by Woodlands Health or at Alexandra Hospital.

They can also call the NurseFirst helpline (6262-6262).

“If any of these services direct you to call 995, please don’t hesitate — just to make sure that everything is safe for you,” advised National University Hospital senior consultant Benjamin Leong, a member of the SCDF’s medical advisory committee.

As part of the SCDF’s non-conveyance policy, on-site treatment is provided where needed, and callers will be advised to see a general practitioner (GP) or visit a polyclinic. They can also call 1777 for a private ambulance.

But sometimes, even when it is not an emergency, patients insist on being transported to hospital. It may be that some expect a free ride or to be given priority once they arrive.

In truth, non-emergency patients conveyed to hospital by the SCDF are subject to a S$274 fee. By comparison, most private ambulance services charge between S$90 and S$260 for a trip to the emergency department.

And while genuine emergency patients conveyed by SCDF ambulances do bypass the usual hospital triage process and “go straight to the resuscitation room”, said Ong, non-emergency patients may face a long wait to see a specialist after being triaged.

“We prioritise whom we see first and whom we treat first based on the limited resources that we have,” said Ong. “Minutes are important.”

In trauma, for instance, there is the concept of the “golden hour”, he noted. “What happens in the first 60 minutes after you sustain an injury has the biggest impact on whether you live or you die.” If patients come in with a non-emergency, they divert “resources, time and attention away from other patients who might be having a true emergency”, he added.

Achieving better health outcomes is precisely what brings operations centre rota commander, Captain Sasi Kumar, professional fulfilment.

“We want to ensure that the patients have been given the best medical attention,” he said. “We really hope that the patients are able to survive. … It gives us a sense of happiness.”

For Ang, she finds meaning in how her role in the SCDF “really makes a difference in people’s lives”. “You see that your efforts (haven’t) gone to waste. They smile at you at the end of the day, and they say thank you.”

Zuhaili enjoys the camaraderie that is part of the job. “There’s nothing quite like going out together with a single purpose — to help someone.”