When tech support is a scam: How India’s call-centre scams became big money

How did the tech support scam industry get so big in India, and how do scammers get victims to fall for their ploy? The programme Undercover Asia finds out from a veteran.

The average wage of a salaried worker in India is around 10,000 rupees (S$172). Scammers may earn that as a base salary and more, with huge performance incentives.

GURUGRAM, India: After working “the whole night for five days”, Leo is off for a weekend getaway in Chandigarh city, in the foothills of the Himalayas.

“It’s really to get out of the frustration and everything,” he says. “Your manager is shouting. Your owners are shouting. It’s all about making money doing this.”

By “this”, he means a typical working day for scammers: Wearing headphones for 10 hours and “trying to manipulate somebody … trying to make bullshit stories sound like they really happened”.

Leo (not his real name) is part of the underbelly of India’s call-centre industry, where scammers trick customers from places such as the United States and the United Kingdom into paying to resolve fake computer problems or issues related to their customer accounts in legitimate companies.

There are vast returns to be reaped. Scammers can make enough for a month, or even a year, in a single night, says Leo. “I’m not kidding,” he tells the programme Undercover Asia.

“If you talk about scope, as in how much money there is to be made, it’s way too big for you to understand it and me to explain it.”

Tech support scams are an international problem, but India has emerged as a leader in the shady industry — to the extent that three call centres in Kolkata recently became the target of vigilante YouTube content creators seeking to give them a taste of their own medicine.

In May, YouTubers Mark Rober, Jim Browning and Trilogy Media released videos that exposed the alleged individuals behind the call centres. The videos also showed the YouTubers’ team pranking the centres by unleashing glitter and stink bombs, cockroaches and rats on their premises.

WATCH: India’s thriving scam industry: Before you call tech support (46:56)

People who work to expose scammers are called scam baiters, and Browning told news site ThePrint.in that over 95 per cent of global scam calls originate from India. Citing his database of IP addresses, he said they originate specifically from in and around Kolkata and New Delhi.

India’s tech support scam industry sprang from its boom in genuine outsourced call centres in the early 2000s, journalist Snigdha Poonam tells Undercover Asia. Poonam, who has reported on these scams, says the boom lasted for about 10 years before the market started to shift out of India.

Then the scammers got busy. They started by “stealing the databases of genuine (customers) from these big tech companies that they’d worked at”, says Poonam. “And (they) started to set up these small centres where you already had that industry network.”

Now in areas like Gurugram, also known as Gurgaon, it can be impossible to tell how much of a business is real and how much of it is a scam operation.

“There’s a floor (on) which they’ll provide genuine tech support, but then they’ll have another set of people who, at a different location in the same office, are making these fake calls,” says Poonam.

HOW ‘TECH SUPPORT’ WORKS

It is difficult to determine exactly how much is lost to tech support fraud. But losses reported to the US’ Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) Internet Crime Complaint Centre hit US$347.66 million (S$476.33 million) last year, more than double the losses in 2020.

In total, US$6.9 billion was reported lost to Internet scams last year, according to the bureau’s Internet Crime Report 2021. In Singapore, millions have been lost too.

Explaining one version of a tech support scam, Leo cites a “customer” searching online for help with a malfunctioning printer who comes across an advertisement that looks like the original manufacturer’s website.

The victim would see a toll-free number to call and end up speaking with the scammers. He may have his computer taken over remotely by the scammers and ultimately lose money through unauthorised access to his personal or financial information.

A pop-up could also appear on victims’ computer screens, resembling an error message from the computers’ operating system or antivirus software, according to the US’ Federal Trade Commission. The pop-up could warn of a security issue and give users a (scam) number to call for help.

Scammers may also impersonate customer support staff of organisations such as banks, utilities and virtual currency exchanges, stated the FBI report.

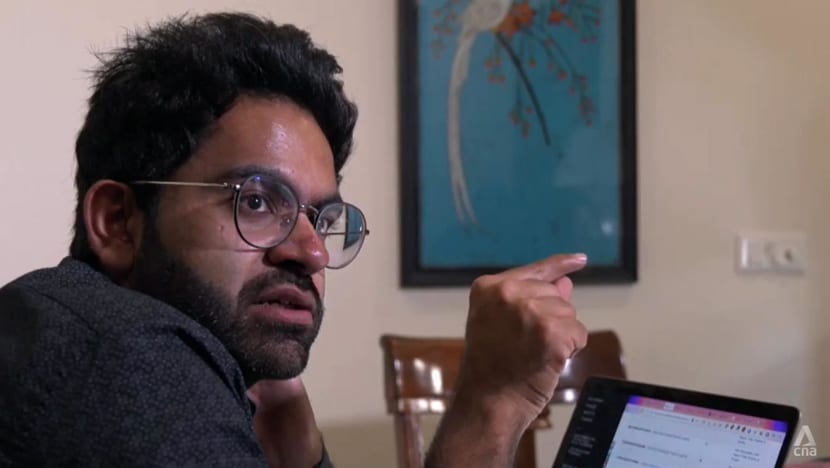

“Whether we like it or not, scams are an outcome of entrepreneurship,” says computer programmer and investigative journalist Samarth Bansal, who has reported on the scamming industry.

Be it from a love scam, job scam or e-commerce scam, digital technology is the “fundamental infrastructure” that has enabled scammers to build trust with their victims before extracting money, he notes.

“A lot of tech is becoming increasingly frictionless,” he observes. “We’re building systems to make it easier for users to transact, to give them a better user experience, but that’s also being exploited by scammers.”

With greater access to high-speed mobile internet in India in recent years, scammers have also turned their sights on the domestic market. Targeting their countrymen is somewhat easier than targeting the overseas market because it does not require knowledge of English or even a call-centre set-up, only a smartphone.

Mangal Rathi, who owns a small upholstery business, recounts how he lost about 25,000 rupees (S$430) to a scammer by unknowingly calling a fake customer care hotline when he did not receive a mobile payment from a customer.

Rathi called the scammer back and was apparently told “the police can’t touch him”.

“The police say that I can forget about getting my money back,” laments Rathi. “What am I supposed to do now?”

‘YOU CAN NEVER SHUT DOWN A BUSINESS’

It is the lack of consequences for scammers that angers scam baiters and recipients of scam calls.

Bansal and Poonam were part of a team who exposed an international tech scam based in Gurugram in 2017. The story ran in the Hindustan Times, a major newspaper, and Bansal expected it to result in multiple arrests.

But “nothing really happened”, he says. “All I got … was a thumbs-up emoticon on WhatsApp (from a police officer) but nothing more.”

Five years on, scam baiters such as Sven (not his real name) continue trying to expose scammers and bring them to the authorities’ attention.

Sven showed Undercover Asia how he gathered evidence against a Gurugram-based scam call centre that was targeting US citizens. He identified its mastermind and roped in a contact in the US to find out the number of complaints — 93 — lodged with the US’ Federal Trade Commission against the scamming company.

He even risked getting into trouble by gaining access to the company’s computer systems to gather proof. But the police left him disappointed when, according to him, they said it “it wasn’t under their jurisdiction”.

The lack of enforcement was also a cause for angst among Undercover Asia viewers, who noted that scammers hurt more than their victims. They also affect Indians seeking to work in legitimate tech companies, said YouTube viewer Virginia.

She has seen managers for customer support roles being less willing to hire Indians because some end users “refuse to work with anyone who has an Indian accent and demand to speak with someone who doesn’t, or the support calls will drag on much longer because people are afraid of being scammed”.

Some viewers lauded the scam baiters while others shared their tactics for dealing with scam calls.

Although the police conduct raids and may disrupt scam operations, proving that scammers cheated people abroad can be difficult, notes Poonam. “They start hunting through their routers and their computers and their servers, but what are they going to find?” she questions.

The police may uncover the names of supposed victims overseas and “the exact amount in pounds or euros or dollars that (scammers) would charge … them, but that’s not proof of anything”, she says.

Industry insiders agree it is difficult for the authorities to stop them for good.

While some scammers feel bad enough about cheating victims — many of whom are senior citizens — that they quit, there are others who do not believe their actions constitute stealing.

“If I convinced (the person to) take out the money from (her) bank and deposit it in some other account, then … I’m extremely talented,” says a former scammer who earned enough to splurge more than 85,000 rupees on her 20th birthday.

WATCH: Confessions of tech support scammers — how we justify what we do (4:17)

As for Leo, he has reinvented his role after seven years in the business: He now helps others who want to set up a scamming operation.

“If somebody has money (and) wants to get into this business, I help him out from the A to Z of it,” he says.

He helps them secure a place to operate, get hold of servers, hire staff to handle calls, and set up ways to ensure victims’ monies are channeled back to them, including via cryptocurrency.

He tells his clients they can recoup their “investments” in two months. But in truth, it could be as quick as 15 days.

“You can shut down an office. It’s possible; it does happen a lot,” says Leo. But “you can never shut down a business”, he declares.

Watch this episode of Undercover Asia here.