What’s the way forward for Indonesia and China in the Natuna dispute?

Tensions with China have led Indonesia to step up defence around the Natuna Islands. But the archipelago wants to be known for tourism, its regent tells the programme Insight.

Unlike its other South China Sea disputes over sovereignty, China is publicly only claiming historical fishing rights in the waters off the Natuna Islands.

NATUNA, Indonesia: The risks are “very high” whenever Natuna fisherman Indra goes to sea. Waves can reach up to eight metres during the monsoon, and he remembers his boat once nearly capsizing during a “terrifying” storm.

But for him, the sea is life. “I love being at sea,” said the 40-year-old, who goes by one name.

On a good day, he can catch up to 200 kilogrammes of fish, some of which ends up on dinner tables in Singapore.

But there is a growing concern: Encounters with larger vessels from China, Thailand and Vietnam in his traditional fishing grounds north of the Natuna Islands.

“Their vessels are huge. Ours are small. One night, our vessels crossed paths. You couldn’t help but feel so anxious,” the father of four told the programme Insight.

“Fish are still abundant in Natuna, but if those vessels keep entering our waters, it’ll be hard for us to catch fish … What will happen to our grandchildren? What will they eat if those ships roam freely in Natuna?”

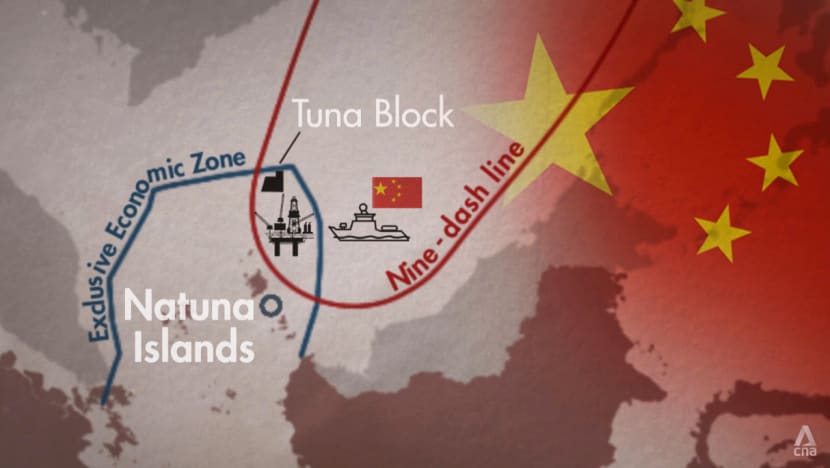

The Natuna islanders’ fishing grounds fall within Indonesia’s 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) — but also overlaps China’s nine-dash line claiming most of the South China Sea.

This overlapping claim has led to tensions, even though the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016 found the nine-dash line to have no legal basis, in a case brought by the Philippines.

In 2017, Indonesia named the waters north of the islands the North Natuna Sea to resist China’s territorial ambitions.

And although Indonesia is not a claimant in the South China Sea disputes between China and several Southeast Asian countries, it has been “rapidly hardening” the Natunas with military installations, noted Ridzwan Rahmat, principal defence analyst at military publisher Janes.

They include a submarine building facility, piers that can hold larger warships such as amphibious assault ships and frigates, and bases for military aircraft such as Apache helicopters and the Sukhoi.

“Over the last five years, I’ve not seen an island in Southeast Asia that’s been militarised as rapidly as in Natuna Islands,” said Ridzwan.

This is Indonesia’s response to China’s deployment of “large assets — military (and) coast guard assets — into waters claimed by Jakarta as part of its EEZ”.

Last year, tensions simmered when China reportedly told Indonesia to stop drilling for oil and natural gas at a temporary offshore rig.

Indonesia’s reply, according to an Indonesian lawmaker interviewed by Reuters, was that it would not stop drilling because it was a sovereign right.

Both countries kept the episode under wraps, but Reuters reported that over the next four months from around June 30, Chinese and Indonesian ships shadowed each other around the oil and gas field.

INDONESIA CAN ‘PUNCH BACK’

Analysts note that Indonesia’s military assets pale in comparison with China’s, despite improved capabilities over the years.

But they do not doubt that Indonesia will defend its territory, notwithstanding the fact that China is Indonesia’s biggest trading partner and one of its biggest investors.

Last August, when Indonesia’s armed forces held their annual joint exercise with the United States Army, it was reported as the biggest edition of the war games to date.

Last month, the Indonesian Army announced that both countries will expand the Garuda Shield exercise to 14 participating countries this year.

Ridzwan thinks what happened in 2012, when China took de facto control of a reef called the Scarborough Shoal, which lies in the Philippines’ EEZ, “won’t happen to Indonesia”.

Indonesia is “able to punch back given the number of military assets that it’s deployed to the region”, he said.

“Beijing understands that if it tries to do what it did (with) Scarborough Shoal … it’s going to suffer from a very big black eye.”

Iseas – Yusof Ishak Institute visiting senior fellow Leo Suryadinata added: “I don’t think that China would — at this particular moment — push too much, so that it’d make Indonesia react (in an unfriendly manner).”

MOVING FORWARD ON TRADE, INVESTMENT

Maritime tensions have not hurt ties on the trade and investment front thus far.

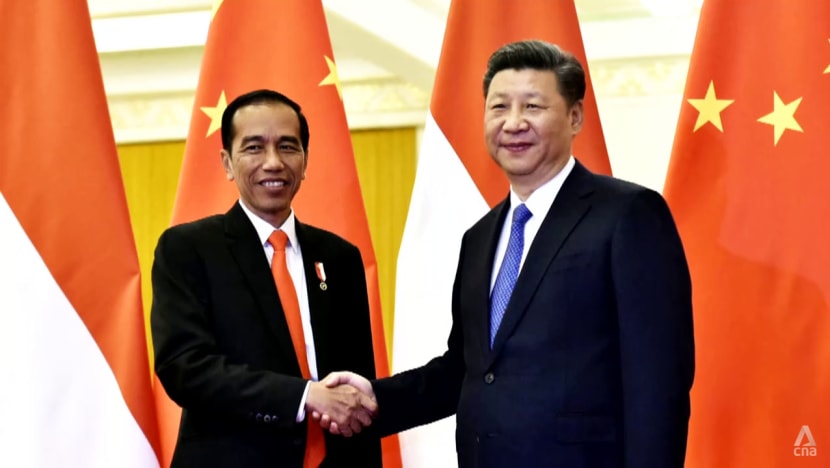

When their leaders spoke over the phone in March, they exchanged views on the Ukraine situation, and Chinese President Xi Jinping said both sides have established bilateral co-operation on political, economic, cultural and maritime affairs, Chinese news outlet CGTN reported.

President Joko Widodo hoped China would continue to support Indonesia’s development, including that of its new capital in East Kalimantan.

Asked about the impact should China cut its investments in Indonesia, Achmad Sukarsono, associate director and lead analyst for Indonesia at risk consultancy Control Risks, said Indonesia can continue to develop its infrastructure without China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

But there would be “significant cuts” outside Java. “Without BRI, Indonesia will fall back on its old Java-centric template focusing on the main island,” he added.

Beyond the oil and mining sectors, Western and Japanese investors are also “reluctant to invest outside Java” because of higher logistical costs and licensing and other issues. “Indonesia can definitely build without China, but should they?” he questioned.

WATCH: The Natuna dispute — can Indonesia afford to go up against China in South China Sea? (46:51)

China-funded projects include the high-speed rail linking Jakarta and Bandung in West Java expected to be completed next year.

It is a “very important project”, which both countries’ presidents “intensely monitor”, said Allan Tandiono, director of project management and business development at PT Kereta Cepat Indonesia China, a joint venture between Indonesian and Chinese railway companies.

“This is important to prove to the world that China and Indonesia can collaborate well to develop infrastructure — public facilities that can bring economic benefits for Indonesia, China and the people.”

JOINT DEVELOPMENT IN NATUNA TOO?

Diplomacy and co-operation are also the way forward for resolving the Natuna dispute, cite analysts. “The option that both countries are looking at now is how to manage movements over the waters through some sort of co-operation,” said Achmad.

“This can be stretched to a joint development of the deep-sea gas resources without fussing about border lines. Indonesia is still far from actively developing the Natuna gas deposit, and Indonesia still needs better technology to detect those hydrocarbon motherloads.”

Victor Gao, vice-president of the Beijing-based Centre for China and Globalisation, agreed that “in any kind of territorial dispute, diplomacy is the best choice”. “War is the last resort,” he said.

War is easy to launch but is very difficult to end. And I think we need to consider the situation not only for the current generation but for hundreds of generations to come.”

Meanwhile, the Indonesian authorities’ greater interest in developing the Natunas has improved the lives of the 80,000-plus islanders, observed postgraduate student Destriyadi Nuryadin, 25. “I can see the changes compared to when I was a boy,” he said.

“There are more places to eat out, which is probably a reflection of a better economy. There are more public facilities including (in) Piwang beach, which make it more comfortable for people to be here.”

Besides defence installations, the islands are being developed for fisheries, oil and gas and tourism, said Natuna’s regent, Wan Siswandi.

In 2018, the islands were added to the list of Indonesia’s national geoparks, which are protected landscapes of geological significance. “Natuna was already known internationally. But we don’t want people to know Natuna as an area of defence,” he said.

“We want people to know Natuna because of tourism.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.