commentary Commentary

Commentary: Vaccine patent row shows need to rethink intellectual property

It was not the promise of a patent that produced COVID-19 vaccines astonishingly fast in the first place, says the Financial Times’ Tim Harford.

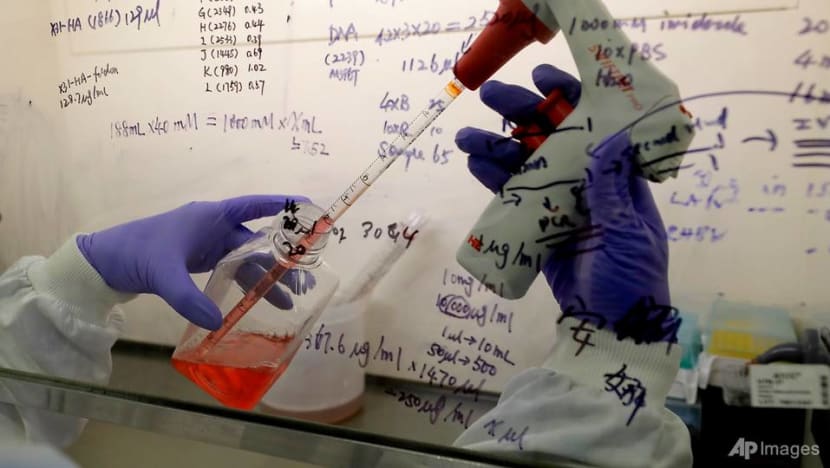

Virus Outbreak Intellectual Property

OXFORD: Everyone knows that intellectual property is sacrosanct, a reward for good deeds and an essential way of supporting creative endeavours.

That, at least, was the response to journalist Matthew Yglesias when he suggested in March that copyright protection should be limited to 30 years, rather than 70 years after the death of the author. (I made a similar case myself a few years ago.)

The writer Neil Gaiman described that concept, with characteristic bite, as “enthusiasm ... for removing income from elderly and disadvantaged authors”, and the twitterati agreed.

READ: Commentary: US-backed COVID-19 vaccine patent waiver has larger implications

How strange, then, that the reaction was so different when the Joe Biden administration surprised most of us with an expression of support for (maybe, someday) waiving COVID-19 vaccine patents.

Thank goodness! Everyone knows that intellectual property is a murderous enabler of “vaccine apartheid” for which there can be no justification.

WHO DO WE PROTECT?

It seems that we approve of boundless intellectual property for nice people and no IP at all for scoundrels. That is not much of a policy.

Once upon a time, monarchs would hand out monopolies to favourites, but a modern society cannot be handing out IP to whoever seems most sympathetic.

Long copyright benefits a few “elderly and disadvantaged authors”, but it mostly benefits the corporations who own a handful of truly profitable properties such as Mickey Mouse and Batman.

And speaking of vaccines, biotechnology has its share of underpaid creatives; just read the coverage of the thankless struggle of people working on mRNA technology.

So let’s start again. Why do we do this intellectual property thing? And is there a better way?

The wonderful thing about ideas is that they can be freely copied, but the terrible thing about ideas is that they can be freely copied. Everyone can enjoy them, but the incentive to create them in the first place seems questionable.

A TEMPORARY MONOPOLY

IP tries to resolve the dilemma. It is a temporary monopoly, artificially created by the stroke of a pen.

The “monopoly” is what rewards creators for their efforts. The “temporary” is what ensures that we can all eventually enjoy the benefits of new ideas at the lowest possible cost: There is no need for King Lear or the wheel to enjoy IP protection in the 21st century.

There is a broad logic to intellectual property, then. But the specifics can be questioned.

For example, just how temporary is the monopoly? F Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby in 1925 and died in 1940. The work only entered the public domain in 2021, after several posthumous copyright extensions, none of which can have been much of an incentive for him to write more.

Then there is the question of what deserves protection.

At the height of the dotcom boom, an economics professor, Alex Tabarrok, was taking a shower when he dreamed up the idea of using cell phones to scan barcodes in a store, compare prices and order the product online. Alas, someone else had beaten him to the patent office by mere months. The idea, once unthinkable, was by 1999 rather obvious.

But why should society award 20 years of monopoly rights for the kind of idea that an amateur could dream up in the shower?

Tabarrok suggests — rightly — that a 20-year patent should be awarded only if the inventor can prove the idea was expensive to develop. Without that, a five-year patent should be sufficient reward — and, more importantly, sufficient incentive.

IP FOR VACCINES

And what of the intellectual property waiver for COVID-19 vaccines? It all seems like a sideshow. It was not the promise of a patent that produced the astonishingly rapid results; governments spent money to accelerate the process beyond the pure market incentive.

READ: Commentary: Glaring vaccine gaps across the world are too big to ignore

READ: Commentary: World needs a lot more COVID-19 vaccine doses than this

Operation Warp Speed alone spent US$10 billion on Moderna, Oxford/AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and others — and governments should spend more; that sum is trivial compared with the benefits of these vaccines.

Just as the patent played a subsidiary role in encouraging the invention, it also plays a minor role in slowing the spread of that invention.

We urgently need to produce more vaccines but the short-term constraints on that are available production lines and raw materials, while the medium-term constraints are non-patentable expertise — the ineffable know-how that comes with experience.

An IP waiver, or the threat of one, might expand production next year. Then again, it might not: Without IP protection, vaccine manufacturers might guard their non-patentable know-how more jealously.

If we are to produce the extra doses we need, we should focus on lifting every constraint.

Perhaps patents fall into that category, but it seems more likely that they are a distraction from the expense of subsidising new factories and more doses for low-income countries. We should spend that money willingly, both for moral and for self-interested reasons.

READ: Commentary: How Operation Warp Speed created winning vaccines

As for intellectual property, the system needs to change in a hundred ways, some of which require the weakening of intellectual property and the strengthening of other incentives such as prizes and targeted subsidies.

When we think through those changes, we should spend less time looking for victims and villains in the creative sphere — and more time thinking about where new ideas come from, and how they can be nurtured.