commentary Commentary

Commentary: Learning another language has benefits - just not the economic kind

Learning a foreign language becomes pointless in this era of global English and machine translation, says the Financial Times' Simon Kuper.

File photo of students. (Photo: AFP/Martin Bureau)

LONDON: I’m a rootless cosmopolitan, so we’re moving the family to Spain for a year.

The kids are up for it. Growing up with anglophone parents in Paris, they speak French and English, and once you know one Romance language, learning another is a cinch.

“Lexical similarity” is the measure of overlap between word sets of different languages; the lexical similarity between French and Spanish is about 0.75 - where 1 means identical.

I want the children to have such good Spanish that they can say everything, understand everything, have deep friendships and be fully themselves in the language for life. That’s what matters, not perfect grammar.

But for all my emotional commitment to multilingualism, I know its usefulness has diminished. How should we think about learning languages in this era of global English and machine translation?

MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING?

I spent an intensely rewarding decade learning German. Yet I now keep encountering younger Germans who insist on speaking their practically native English to me. This is true across Europe: About 98 per cent of pupils in primary and lower secondary schools in the EU are learning English.

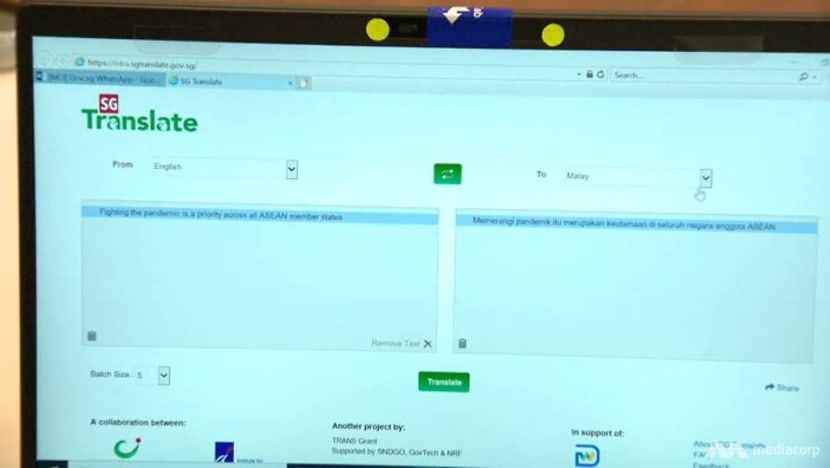

Meanwhile, machine translation is catching up with the human sort. I’ve been having successful email exchanges with Spaniards by putting my English text through Google Translate. It’s imperfect, but still much better than my Spanish.

READ: Commentary: Higher learning institutes need to change strategies to groom IT talent

The utility of language-learning will only keep diminishing. Already, many publications around the world now translate some of their articles into English.

In five years’ time, Le Monde and China’s Jiefang Daily could whack 20 articles a day through machine translation, hire underpaid young anglophones to polish them and, presto, they’ll be global newspapers.

The corollary to all this: Learning a language badly is becoming pointless.

READ: Commentary: Enough of digital devices, let’s hear it for physical books

In my generation, people spent years at secondary school breaking their heads on French or German grammar.

Most emerged able to order beers and perhaps read a basic news story. I suspect they would have had a more enriching experience spending that time studying medicine, history or statistics.

Language teachers will disagree, but then they would, wouldn’t they? They have jobs to protect.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

I’m equally sceptical of translators who insist they can never be replaced by a machine.

True, machine translation is often faulty, machines can’t (yet) communicate through body language or eye contact, and some algorithms are sexist.

For instance, in gender-free languages such as Turkish, today’s algorithms tend to assume an engineer is “he”.

But most human translators are faulty too. One man did such a poor job translating a German text into English for publication in the FT that I spent an afternoon rewriting it.

Moreover, humans can produce sexist language without help from machines, and their algorithms are harder to adjust.

READ: Commentary: Here’s why every organisation should hire a diversity manager

In short, rather than spend years learning bad German, just install a translation app on your phone.

If you do learn a language, go for excellence. If you have children, immerse them in it from birth.

Wall Streeters sending their kids to Mandarin-speaking preschools may be hilarious, but they are choosing the most efficient route.

PRACTICALLY ENGLISH

I still wrestle with the issue of anglophones learning foreign languages. Here the utilitarian argument is weakest of all. If the global language is your mother tongue, your brutal self-interest lies in forcing foreign interlocutors onto your home turf.

And anglophones don’t have the easy linguistic wins that francophones do, because no major foreign language is particularly close to English.

I took these issues to Mark Dingemanse, a linguist at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

He agreed, up to a point, on the weakening utilitarian case for languages. Dingemanse is a gifted linguist who speaks a Germanic language and lives 10km from the German border, yet even he often finds himself speaking English to Germans.

For other languages, he sometimes uses machine translation. “I think everyone does,” he says.

Still, he points out, humans can do something machines can’t: Ask each other for clarification. We do that constantly in conversation: “Really? You sure? What do you mean?”

READ: Commentary: The benefits of bilingualism go beyond knowing two languages

READ: Commentary: What hope do monolingual parents have in raising bilingual children?

He worries that machine translation might dilute our accountability for what we say.

MULTIPLIER OF OUR LIVES

But he warns me against focusing on the utilitarian value of languages. Multilingualism, he says, is the standard human condition. Most people alive today speak multiple languages. That shapes who they are.

In the Ghanaian village that Dingemanse studies, people use different languages for different registers: English for some purposes, various Ghanaian ones for others. Each language has its own domain.

He asks me: “How would you feel if you suddenly became monolingual?” I shudder: I’d feel diminished as a human.

He explains why that is: A multilingual person can be multiple people, inhabiting multiple worlds.

READ: Commentary: Language barriers block businesses off from Indonesia

“The pleasure of mastering different languages is something humankind will never lose,” he says. “As the linguist Nick Evans wrote, we study other languages because we cannot live enough lives. It’s a multiplier of our lives.”

The enrichment, Dingemanse emphasises, “is not just economic or utilitarian”. He’s right — but it’s best to know that before you start.