Commentary: Should the UK recognise a new Myanmar diplomat appointed by the junta?

The impasse over the Myanmar coup has thrown up new challenges for countries seeking to navigating the politics of recognition, say Alistair D B Cook and Mely Caballero-Anthony.

FILE PHOTO: Myanmar's ambassador Kyaw Zwar Minn gestures outside the Myanmar Embassy, after he was locked out of the embassy, and sources said his deputy had shut him out of the building and taken charge on behalf of the military, in London, Britain, April 8, 2021. REUTERS/Toby Melville/File Photo

SINGAPORE: The UK Government announced the appointment of its new Ambassador to Myanmar international aid practitioner Pete Vowles last Friday (Jul 23).

It also issued a statement the same day acknowledging receipt of a notification that a new Charge d’Affaires has been appointed by Myanmar to lead its UK embassy.

This followed developments in April which saw then Myanmar Ambassador to the UK, Kyaw Zwar Minn, locked out of Myanmar’s UK embassy by his staff.

Since then, there has been speculation over whether the UK government would recognise a new military-appointed Myanmar Ambassador, and if it did, whether such an act could confer legitimacy on the State Administration Council as the Government of Myanmar.

What then would this mean for the National Unity Government, formed by elected lawmakers ousted in the February coup?

READ: Commentary: Defiance in Myanmar’s diplomatic ranks threatens the military’s power

ATTEMPTS TO GAIN INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION

Although the military have made several attempts to gain international recognition of its State Administration Council, domestically, they have experienced huge resistance.

Anti-junta demonstrations and protests have persisted, most recently on Martyrs’ Day on Jul 19 to oppose the military takeover of government.

The international community’s passive position that a peaceful resolution of the situation is needed remains unchanged. Perhaps this is why it has had little success in making progress on the issue.

The United Nations has been unable to arrive at a consensus towards the turmoil in Myanmar. The only agreement that the UN Security Council Permanent Five members have reached through public statements is that the international response to the situation in Myanmar should support the ASEAN led process.

Even US Secretary of State Antony Blinken who expressed deep concern about the situation in Myanmar simply urged ASEAN to take action to end the violence and restore democracy in the country in a video conference with his ASEAN counterparts in mid-July.

These contending positions have not only led to an impasse but also presented fresh challenges to how governments should deal with the military regime under the present circumstances.

As states navigate the world of diplomacy and realpolitik, their engagements with Myanmar will inadvertently come under huge scrutiny.

READ: Commentary: Could defecting soldiers in Myanmar bring down the military?

The impasse in Myanmar has heightened sensitivity to any signs of movement in the international community’s posture towards Myanmar.

This is the reason why there is a focus at present on the relationship between Myanmar and the UK, and a few months ago on the composition of Myanmar’s participation in the ASEAN Leader’s Meeting in April.

It boils down to the politics of recognition, perceptions, and who can speak on behalf of whom and to what end – as well as whether such actions could shift the goalposts on the situation to the detriment of the Myanmar people.

READ: Commentary: Has Myanmar coup sparked rethinking on non-interference among ASEAN countries?

THE POLITICS OF AMBIGUITY

In the realm of diplomacy, nuance matters. There is the diplomatic practice, however, that countries recognise states not governments.

This provides countries flexibility in their diplomatic engagements, particularly when dealing with a state whose military has taken control and is deemed illegitimate by its own people and in the eyes of the international community.

It is over this point that the diplomatic world and the public have diverged. Many people see any external recognition of a diplomatic appointee as affording the military with legitimacy to run the country at the expense of its democratically elected government.

This contrasts with diplomatic law as enshrined in the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations that ambassadors need their credentials recognised by the host country but that diplomatic ranks lower than that of Ambassador do not. Myanmar’s appointment of a new Charge d’Affairs to the UK is technically a matter of process not politics.

This legal differentiation may come to pass and see the newly military-appointed Ambassador take the post of Charge d’ Affaires ad interim in the UK, bypassing the need for formal UK government approval.

But he still needs to get a UK travel visa as he is presently in Myanmar. This is not as straight-forward as it used to be pre-coronavirus. Myanmar is on the COVID-19 Red List which only allows entry to British, Irish nationals or travellers who have residency rights in the UK.

READ: Commentary: Thailand as a model? Why Myanmar military may follow Prayuth's example

So the military-appointee will still require UK government authorisation for a visa that allows him to take up his diplomatic post as Charge d’ Affaires in London.

Against the international opprobrium on the military regime in Myanmar, how the UK Government navigates its position can be a source of contention.

Would a position recognising the Charge d’Affairs in any form be consistent with the official UK position opposing the military takeover of government in Myanmar or wash with the UK public? How does this diplomatic ambiguity inform the diplomatic engagements by other countries on Myanmar?

READ: Commentary: Myanmar learnt the wrong lessons from Indonesia’s political transition

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASEAN’S DIPLOMACY ON MYANMAR CRISIS

Back in April, ASEAN faced a similar challenge over whether the presence of a military representative at the ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting constitutes recognition of the Myanmar military as the Government of Myanmar.

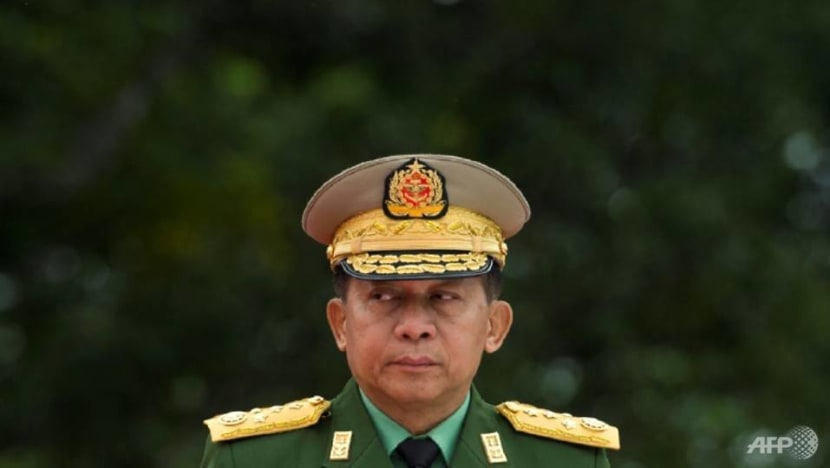

Senior General Min Aung Hlaing eventually attended in his position as Commander-in-Chief and was not afforded official recognition as Head of Government. This recognised the de facto control the military has over major entry points and government buildings but falls short of de jure recognition as the internationally recognised Government of Myanmar.

While this diplomatic ambiguity has allowed ASEAN to initially agree on a regional approach to help address the Myanmar crisis, this approach has yet to break the impasse.

It is now three months since the ASEAN Leaders Meeting was held in person at the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta and there is still no answer from the ASEAN Chair, Brunei Darussalam, on the proposed appointment of a Special Envoy to Myanmar for the regional bloc as part of the agreed Five-Point Consensus.

Nearly six months after the military coup in Myanmar, over 900 people have been killed and over 5,300 arrested, charged or sentenced by the military. COVID-19 is rampant in Myanmar, and many are going without the medical attention they need.

Some vaccines and medical equipment are en route from China, the EU and Japan, but not nearly enough or quick enough to those most in need. Food prices are rising and people are suffering from the devastating impact of insufficient access to necessities since martial law was imposed.

READ: Commentary: Myanmar’s post-coup economy is in free fall

CHARTING OUT A NUANCED DIPLOMATIC APPROACH TO MYANMAR

As Myanmar faces the grim consequences of dual crises of a military coup and the COVID-19 pandemic, more questions will be raised over the international community’s ability to respond and help the people in Myanmar.

The pressures will continue to mount on ASEAN to act on the implementation of its Five-Point consensus. So will it be for other countries like the UK that have been at the forefront in opposing the military regime in Myanmar.

How these countries will calibrate their diplomatic engagement with the regime in Myanmar while responding to the worsening humanitarian situation in the country remains to be seen.

READ: Commentary: The ups and downs of ASEAN’s dealings with Myanmar

While the people in Myanmar remain resilient in the face of this adversity, they would certainly hope that their neighbours and the rest of the international community will not reduce their interest to focus on the politics of recognition at their expense.

While the world of diplomacy is defined largely by nuanced positions states take for national interests, balancing this ambiguity against the urgent need to invest in a more substantive and consistent agenda to find a political resolution and support the people in Myanmar is urgently needed.

Dr Alistair D B Cook is Coordinator of the Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Programme and Senior Fellow at the Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Professor Mely Caballero-Anthony is President’s Chair in International Relations and Security Studies and Head of Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, at the same school.