Who's Jack? Meet the second and third generation heirs to Jack's Place

What keeps a heritage dining icon like Jack’s Place going? CNA Lifestyle talked to the late founder’s daughter and grandsons who are steering the family business today.

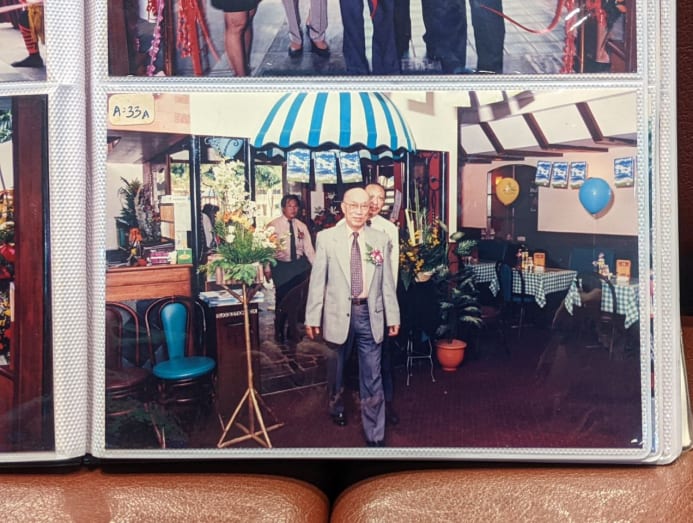

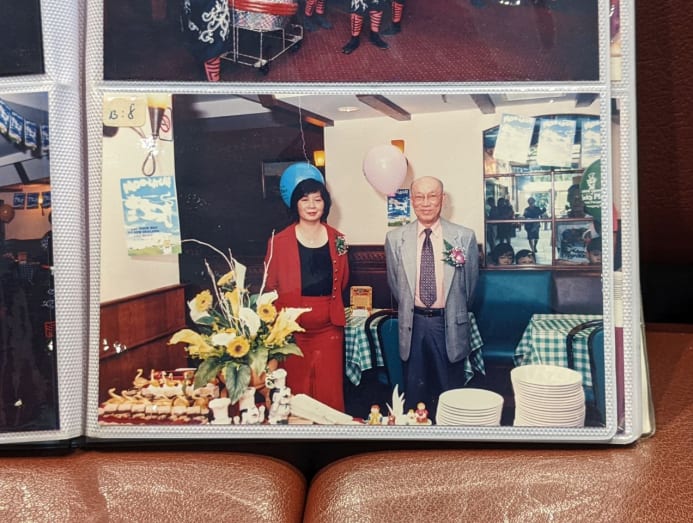

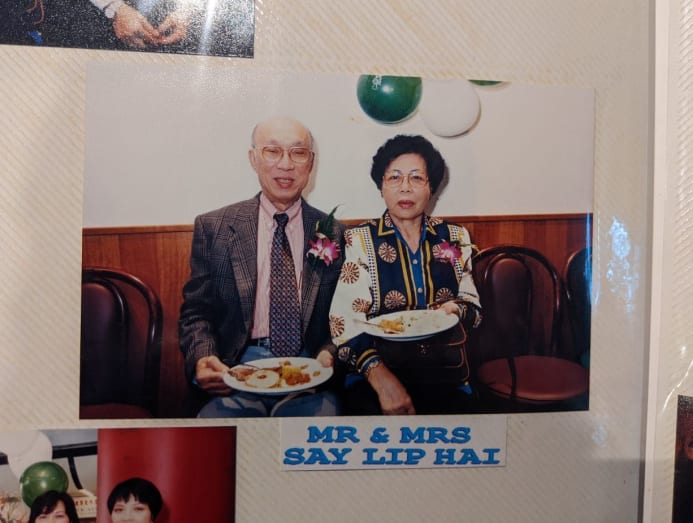

Meet the family behind Jack's Place: An old photo of Susan Say with her father, the late Say Lip Hai, and Susan with the new generation, grandsons Jason Ong (left) and Alvin Say. (Photos: Joyce Yang)

Anyone who grew up in Singapore would know their green and white checkered tablecloth anywhere. You may even associate it with sizzling steaks and servers marching from table to table with gravy boats in hand. After all, Jack’s Place is nearly as old as Singapore.

Before western-style restaurants were a dime a dozen, Jack’s Place was something of a luxury reserved for candlelit dinners and special occasions. Today, the steakhouse is a household name that requires no introduction. But what’s the backstory? Also, who’s Jack?

CNA Lifestyle spoke with Susan Say, the third child of Jack’s Place’s late founder; and his grandsons, Alvin Say and Jason Ong, to find out.

FROM MILITARY COOK BOY TO RESTAURATEUR

“My father was a very simple man,” said Susan, 67, remembering her late father, Say Lip Hai. “He came from Hainan in China, and was not educated.” Say was a cook boy serving British troops when he first encountered western-style fare and learned to make roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

In 1967, he started Cola Restaurant in Sembawang. There, he served mostly Anzac and British troops who docked at a shipyard nearby. But, one day, a woman walked in and ordered the roast beef he perfected all those years ago. She fell in love with it at once. When her husband learned of it, he made Say a business proposal. The man’s name was Jack Joseph Hunt.

When Say came onboard Hunt’s pub along Killiney Road, he entrusted Cola Restaurant to Susan’s elder siblings. She was only 14 when she tagged along with her father to Jack’s Place. “In the olden days, we did everything from ordering to cashiering ourselves. We peeled prawns and potatoes in the kitchen. If the chef was not around, we would help cook too,” she recalled.

In 1974, Hunt returned to England and sold the business to Say for S$28,000. As the new showrunner, his first move was to turn the pub into a restaurant – an Italian one at that. “If you look at our old menu, you’ll see that our first logo was an Italian chef. He’s dressed up differently from our current fourth generation logo,” Susan explained, adding that Say adopted other culinary influences along the way. French cuisine, in particular, left an indelible mark on the menu. “Jack’s Place educated Singaporeans on what escargots were.”

In the early days, their S$3.80 set lunches were a hit among oil riggers and office workers along Orchard Road. Say made them with only the freshest ingredients, which he procured from the market every morning on his trusty Vespa. “He always said, my motorbike is my leg,” Susan said. “He would tell our customers, ‘the chicken you’re eating right now was in its cage just this morning’. He also used ikan kurau (Indian threadfin) to make fish and chips, which was an expensive fish. When customers asked how he made any money from it, he would say it’s for advertisement.”

It worked, obviously, and the 60-seater outlet at Killiney Road was soon overwhelmed. So, in 1977, Say opened his second outlet at the former Yen San Building. Whenever the Killiney outlet had a long queue, he would personally ferry customers to the Yen San outlet down the road. A shuttle service operated by the boss himself, if you will.

“A lot of customers remember Jack’s Place Yen San because that’s where they went to “paktor”,” Susan said. The restaurant was located in a small alley, between the present Apple Store Orchard and The Heeren, and quickly gained a reputation for its romantic ambience.

Jack’s Place was also a popular watering hole then. In Susan’s memory, the bar counter was always packed and Say would order bottles of whiskey by the hundred. Closing time was 11pm, but they frequently extended their operating hours to serve pilots in the area. “My poor father sometimes had to wait for them till 1am. I always say that he succeeded because of his hard work. He spent all his time, every day, to make it work.”

In the 1980s, Say’s tenacity paid off as he ventured into the heartlands. Jack’s Place Ang Mo Kio was their first foray, and remains the brand’s oldest outlet today. Incidentally, it was also the birthplace of their green and white checkered tablecloths, which used to be blue-coloured. Because this outlet started out as Jack’s Garden Ang Mo Kio, they were given a facelift to suit its theme. In fact, the iconic linen was handsewn by Say’s wife—a sight that is imprinted on her grandson to this day.

“I remember Popo sewing, and it was always in the afternoon,” Alvin said. “She cooks lunch and dinner for us, so she would sew the tablecloths during the lull period in between. Her sewing machine was the old-school sort, so she had to spin the wheel and pedal.”

“OUR CHILDHOODS WERE VERY MUCH SPENT AT THE OUTLETS”

While Susan described her father to be a serious man of few words, his eldest grandson remembered otherwise. “Ah Gong to his grandchildren was very different from a father to Susan. Hers is stern, ours is nice, caring, and thoughtful,” Alvin said. Now the chief operating officer of JP Pepperdine, the 40-year-old fondly looked back on his childhood:

“On Fridays, the cousins would stay overnight so we could all go out with Ah Gong the next day. He would squeeze seven of us in his classic Volvo and take us to the McDonald’s at Serene Centre. They said that I am his favourite grandson, so they asked me to sit beside him. Then maybe Ah Gong will give us more pocket money.”

“He’s very generous,” Susan quipped. “Always give them pocket money. Quite a lot one.”

For Jason, Jack’s Place was like a “daycare” centre. “My mom worked at the Bras Basah outlet, so I would walk over after school. My Saturdays would be spent at the Killiney Road outlet with Aunt Susan, who will bring my cousin and me for Taekwondo lessons,” he said. Since young, the cousins’ parents have always shared that life and work are inescapably intertwined. “Our childhoods are very much spent at the outlets,” Alvin added.

Then came the nineties, which saw Jack’s Place’s corporatisation. Along with it came new departments and ventures, which gave Alvin and Jason no lack of places to work part-time during their school holidays. But did they always know they would someday help run the business?

“It was only in university that I seriously thought about it. When you’re young, you just think it’s fun to work together with your cousins,” Jason said.

For Alvin, there was a feeling of inevitability. “Growing up, there was a part of me that thought, maybe not. We could see the difficulty and challenge because we didn’t see our parents much as kids,” he conceded. “But as you grow older, you start to see their fruits of labour and how the family business put us through university. Ah Gong worked so hard to build his legacy. As the eldest grandson, I do feel the obligation and responsibility.”

ONE EYE ON THE FUTURE, ANOTHER ON THE PAST

What separates a heritage brand from a brand with heritage? In this cutthroat industry, straddling nostalgia and innovation is a delicate balancing act. For the trio, it was all about keeping with the times without leaving Jack’s Place’s regulars behind. Testament to their philosophy is one menu item which has been around since the seventies.

“The signature Hainanese oxtail stew is actually influenced by the locals and not the British. That’s why it has all these herbs, which you seldom find in western cuisine,” Susan explained. However, some might call it an acquired taste. That explains why it is only available at their Bras Basah and Parkway outlets, which attract an older clientele who grew up with it. They only serve it at lunchtime on select days, where a queue starts as early as 11am.

“For us now, we don’t really eat spare parts because we prefer meatier cuts. If I served the oxtail dish to you, you’d probably find more bones than meat,” said Alvin.

In the same way, fans of the oxtail stew aren’t crazy about truffle fries. To whet the appetite of younger customers, the culinary team tests new products through monthly promotions. Only dishes which make the cut become mainstays on the a la carte menu. Fusion is a big part of these experiments, but, as it turned out, it’s embedded in Jack’s Place’s DNA all along.

“When they couldn’t find lasagna sheets in the past, they would use kway teow,” Alvin said, recalling how his grandfather used to improvise with local ingredients at Jack’s Place Yen San. “At that time, Ah Gong already had that vision of fusion.”

Over the years, Jack’s Place had become a hotspot for multigenerational family gatherings. The most birthday songs Alvin has heard in a single shift? Seven.

“A lot of customers always tell us, my father used to bring me to Jack’s Place. Now I bring my children here,” said Susan. “We also have an old customer who proposed to his wife at the Parkway outlet, and wanted to book half the restaurant to celebrate their anniversary.”

That old customers keep coming back is perfectly understandable, because Jack’s Place had been intentional about making them feel at home. They offer Asian dishes, like fried rice, so elders in the family have a familiar option. Even after 56 years, their look and feel evoke nostalgia for simpler days when set lunches cost S$3.80 and baked snails raised eyebrows. Among their long-time fans is an 80-year-old woman, whom Susan affectionately calls Chen Lao Shi (Teacher Chen).

“Until today, she comes to Jack’s Place up to five times a week. When she was a regular at Killiney Road, she came three to four times a week. She loves Jack’s Place so much that even after moving to West Coast, she frequents our Clementi outlet.”

Jack’s Place celebrates its 56th birthday this year. Today, JP Pepperdine Group has four brands under their belt, and Jack’s Place alone has 13 restaurants across the island. But when I asked Susan what she wished her father could witness, it had nothing to do with the company’s achievements.

“He will be happy to see our commitment to the staff. In the olden days, my father took great care of them. Sometimes, for staff who work very hard, they would even stash extra money into their pockets.”

According to Susan, some of their long-serving staff have dedicated over 30 years to Jack’s Place. They weathered through the worst of seasons together, from the mad cow disease scare in 2004 to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. And even as the crisis mangled the F&B industry, not a single one of them suffered a pay cut. Instead, senior staff who were vulnerable were assured of their livelihoods and made to stay home.

“We have all committed to his legacy. I think he will be very happy to see it.”