Buried riches? :

Unearthing the dino fossil trade’s true cost

Kevin Kwang |

Dinosaur fossils are today in-demand art pieces for private collectors, with some going under the hammer for tens of millions of dollars. Yet, the costs of such ownership remain a bone of contention.

This full-bodied Stegosaurus skeleton, dubbed “Apex”, was sold for a cool US$44.6 million (S$57.3 million) during an auction by Sotheby’s last July.

The 150-million-year-old fossil is the most expensive dinosaur fossil to be sold to date.

Apex’s owner? Hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin, who bought the specimen and loaned it to the American Museum of Natural History, where it’s being displayed for four years, before it will be replaced by a cast.

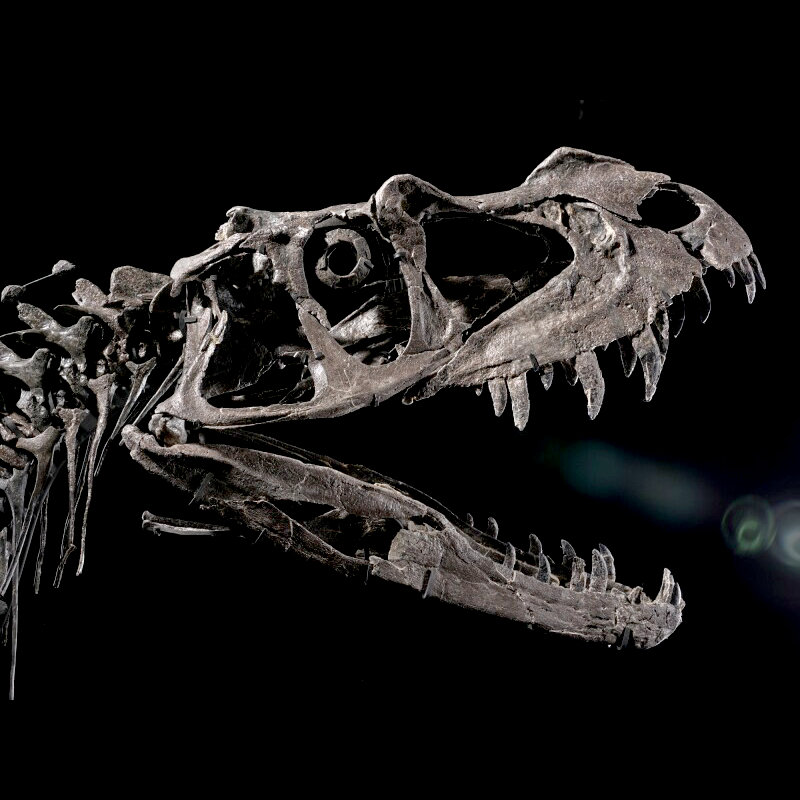

This transaction surpassed that of “Stan”, a rare, almost-complete Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton that went under the hammer at Christie’s for US$31.8 million in October 2020.

Stan’s mystery buyer was later revealed to be the Abu Dhabi Museum of Natural History. The Gulf state’s Department of Culture and Tourism said the skeleton will be a museum highlight when it opens its doors to the public by the end of this year.

These multimillion-dollar transactions are testament to the growing industry dealing in dinosaur fossils, as private collectors muscle in on a space previously the domain of research paleontologists and the museums that conduct these studies.

In fact, of the top 10 dinosaur fossil transactions in the past decade and where some information of the buyer is disclosed, almost all of them went to private collectors such as Mr Griffin.

Top dinosaur fossil trades

Stegosaurus

- Name:

- Apex

- Excavation site:

- Morrison Formation, Platt County, Colorado, USA

- No. of bones:

- 254

- Year:

- 2024

★★

★★Auctioned for

US$44.6 million

Tyrannosaurus Rex

- Name:

- Stan

- Excavation site:

- Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota, USA

- No. of bones:

- 188

- Year:

- 2020

★★

★★Auctioned for

US$31.8 million

Juvenile Ceratosaurus

- Name:

- Unnamed

- Excavation site:

- Morrison Formation, Bone Cabin Quarry (West), Albany County, Wyoming, USA

- No. of bones:

- 139

- Year:

- 2025

★★

★★Auctioned for

US$30.5 million

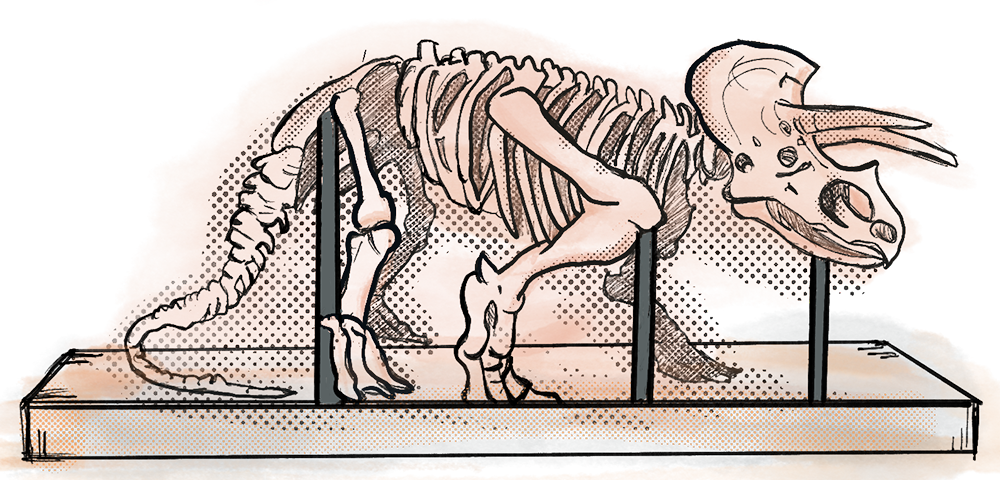

Triceratops

- Name:

- Big John

- Excavation site:

- Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota, USA

- No. of bones:

- 200

- Year:

- 2021

★★

★★Auctioned for

US$7.7 million* *€6.7 million

Gorgosaurus

- Name:

- Unnamed

- Excavation site:

- Lindsay Formation, Choteau County, Montana, USA

- No. of bones:

- 79

- Year:

- 2022

★★

★★Auctioned for

US$6.1 million

Why own old bones?

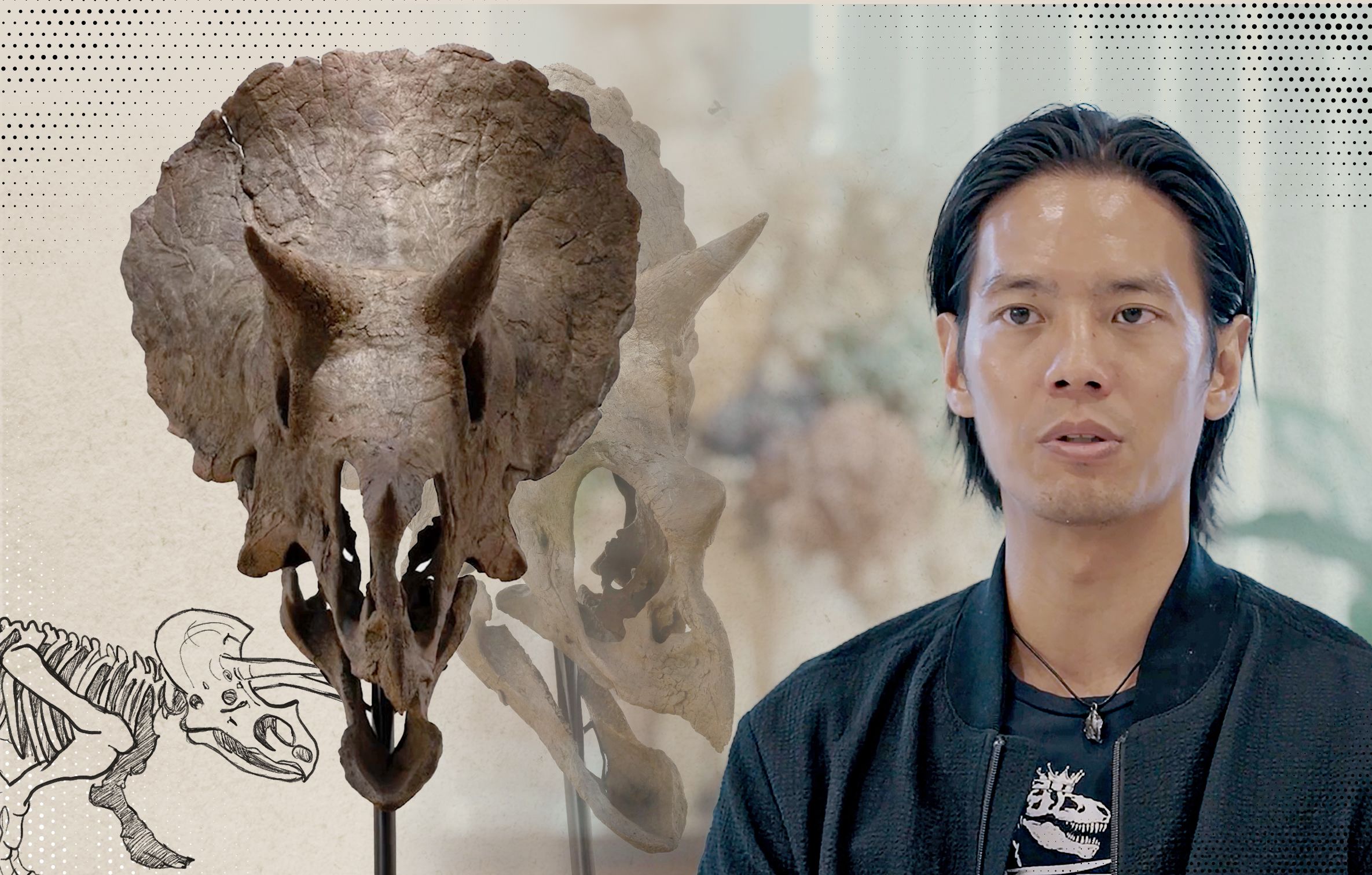

Explaining the growing trend of owning a piece of history through dinosaur bones, Singapore-based fossils dealer Cliff Hartono said the 1993 movie Jurassic Park sparked a wave of interest when it came out.

“Along with that came people’s desire to own a piece like that in their own homes,” said Mr Hartono, the owner of Set in Stone Gallery, who sources and curates minerals, fossils and dinosaurs from around the world for sale in Asia.

The collector’s foray into the business was similarly sparked off by his personal interest in the remains of these prehistoric giants.

The former executive in the finance sector often cites his regular visits to London’s Natural History Museum to admire its exhibits as a reason for starting his own collection and, eventually, trading in his suit and tie for jeans and dig sites.

Others like Philippines-based tech entrepreneur Ralph Wunsch have also put serious money behind this interest. He had purchased an Allosaurus and a Diplodocus at an auction for €3.2 million (US$3.7 million) in 2018, and today displays them in his home accessible only to family and friends.

“I think people who like to collect [dinosaur fossils] are just people who like to appreciate art and history,” Mr Wunsch said.

Rise of the dino trade

As for the business opportunities, Mr Hartono noted that the fossil market today is a “tiny fraction” compared to the art industry.

That said, it would not surprise him if the market gets to the point where it’s a multibillion-dollar industry annually in the long run.

However, fossil trade isn’t legal everywhere. The United States of America and Europe, to an extent, allow for such transactions when private landowners are involved.

But places like China, Mongolia, Brazil and Argentina forbid such excavations and sales. Exports of the fossils from these places are illegal unless permission is given.

Yet, given how lucrative the business had become, black-market trade flourished resulting in fossil sites being raided and specimens surreptitiously shipped to willing buyers around the world.

One of the more high-profile examples of such activities came to light after Hollywood actor Nicolas Cage agreed to return a stolen Tyrannosaurus bataar skull, which he bought for US$276,000 in an auction, to the Mongolian government.

Prospecting for dinosaur remnants

Where then are these in-demand collector items usually found?

Scientists have said that the best fossil hunting grounds lie in desert areas, particularly those with sedimentary rocks.

Paleontologists typically look for fossils in sedimentary rocks that were deposited on the continents, primarily by rivers and streams, or in lakes into which the streams emptied, according to the American Museum of Natural History’s (AMNH) website.

“The famous dinosaur fossil territories are places like the Rocky Mountains and basins of western North America, the Gobi Desert and other deserts in Central Asia, and in South America, the deserts of Argentina, especially in Patagonia,” said Mr Michael Novacek, who is Curator of the Division of Paleontology at AMNH, in a video seen on the site.

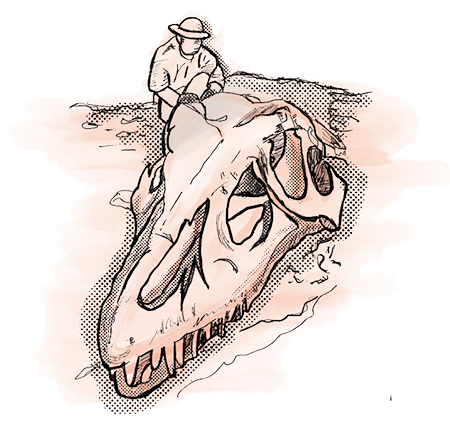

Another experienced paleontologist Walter Stein said during a visit to an unidentified dig site in South Dakota, USA, that one way of identifying possible fossils in the ground is to look out for something that’s “chunky” and “crawling with gypsum crystals”.

The shard having a rusty yellow colour, beyond the grey shale common in that area, is a visual indicator of it being a bone remnant rather than a rock, Mr Stein noted.

The commercial paleontologist is known for being the man who discovered “Big John” - the world’s biggest Triceratops fossil ever found. It sold for €6.7 million in 2021.

How do you get the bones out from the ground?

Identifying dinosaur fossils may seem like searching for a needle in a haystack, and recovering them from the ground poses a different set of challenges.

That’s because these fossils are brittle by nature and, once exposed to the elements upon being discovered, can quickly disintegrate if not managed swiftly. Depending on the find, measures could range from dripping consolidants (or simply put, glue) to creating a “field jacket”.

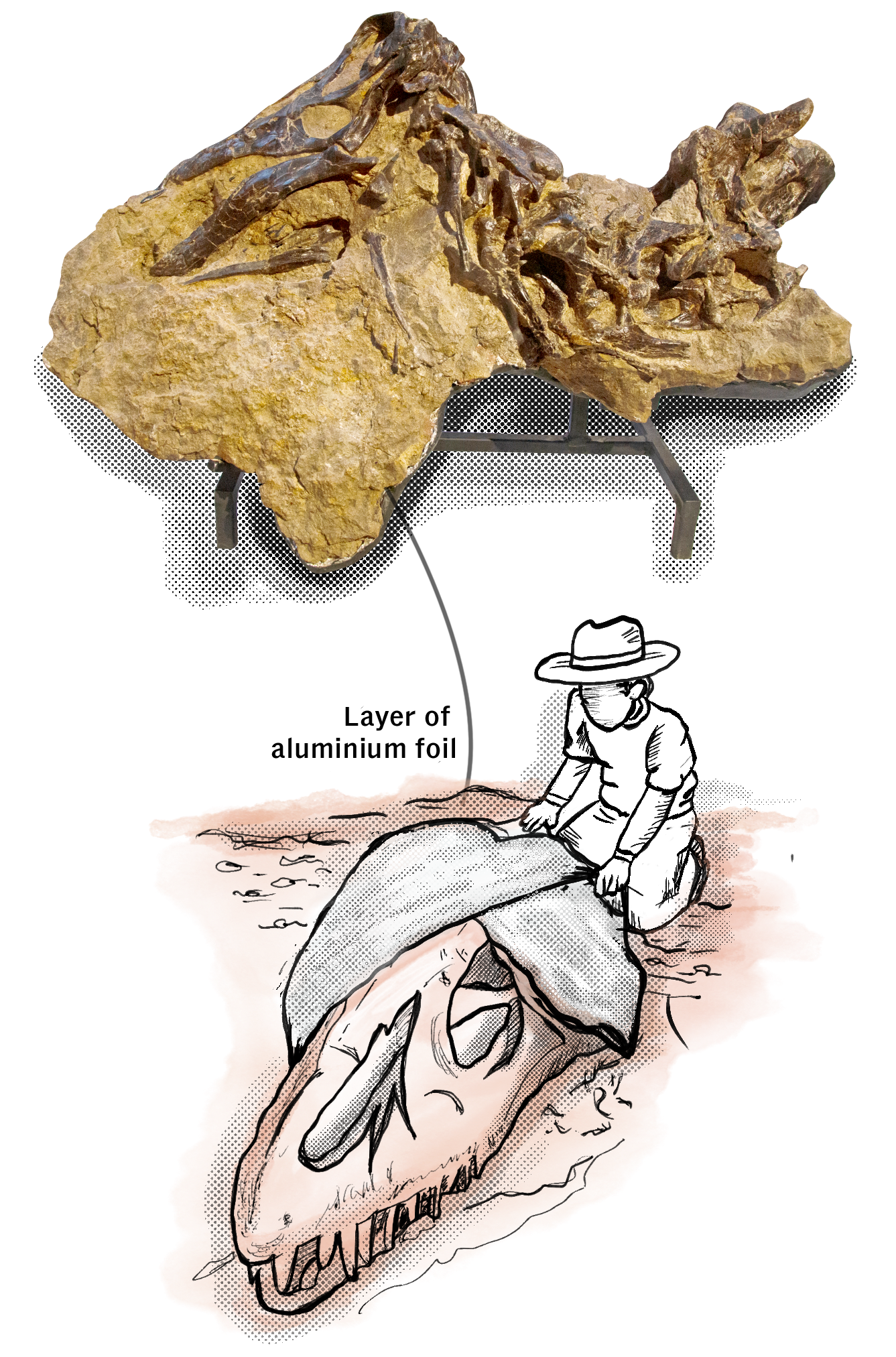

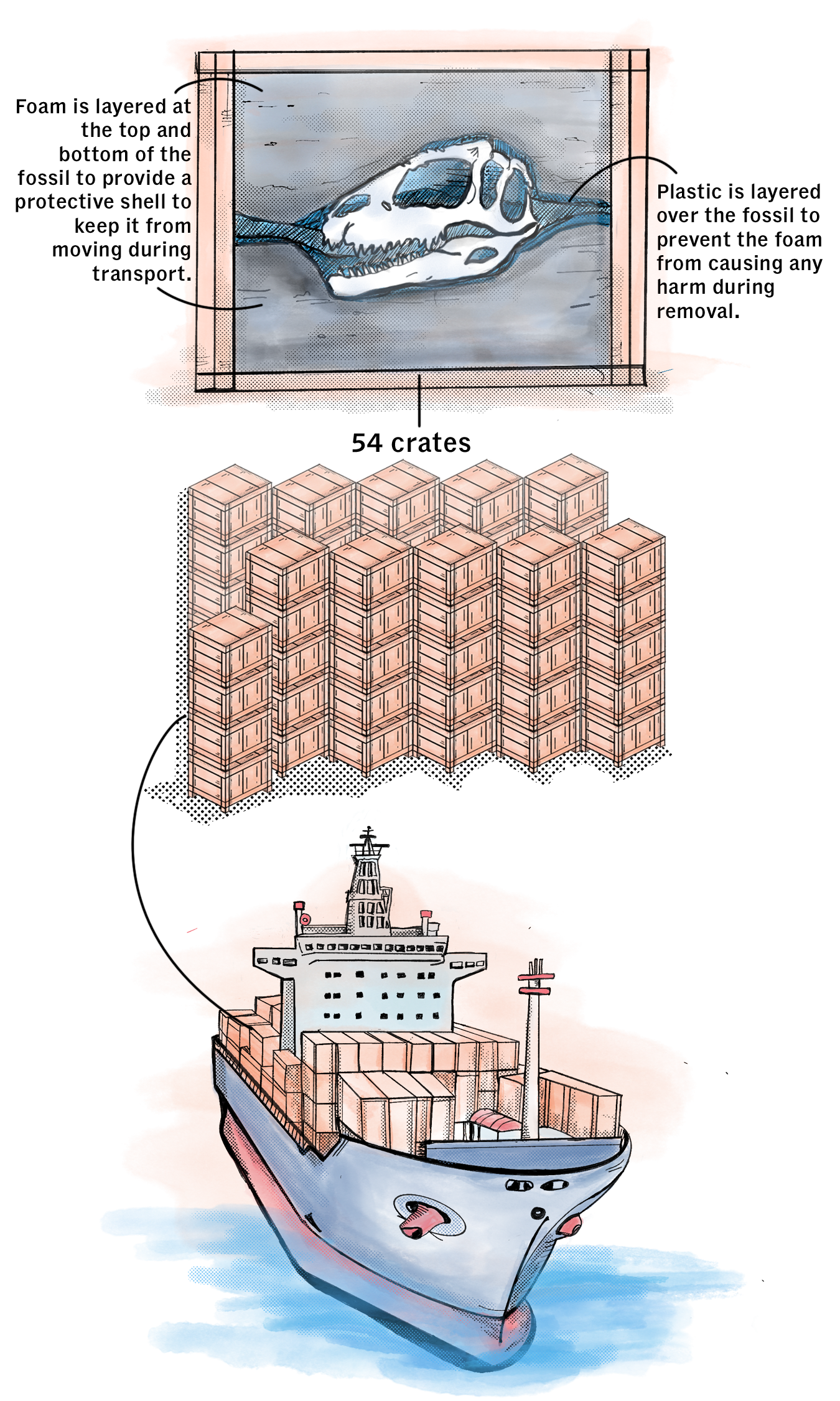

This process would require applying a layer of aluminium foil over the fossil, leaving no air between the fossil and foil so as to avoid the bone collapsing on itself. Once done, plaster is then applied over the fossil to preserve it for transportation. This way, the plaster will not damage the fossil when it’s removed.

This was a process witnessed by Dr Tan Swee Hee, assistant head at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, when he went to Wyoming, US, as part of the process of purchasing the three sauropods from Dinosauria International.

The three dinosaur fossils were bought for S$8 million, which included the excavation, preparation, shipping and on-site installation, the professor said in an interview.

How are fossils shipped and mounted?

It’s safe to say that buying a fossil is way more complex than just the click-and-collect nature of online shopping today.

Dr Tan said just excavating, preparing and creating the mount for one of the three dinosaurs seen at Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum took about two years to complete.

This was followed by shipping them by sea from Wyoming to Singapore. The dinosaurs were shipped individually to minimise risks - “If something happens to the container, I will lose one and not all three at the same time,” the professor explained - and the journey took a month each.

A total of 54 crates were used to transport the dinosaurs over, including hefty pieces like the pelvic bone that weighed about a tonne each, said Dr Tan.

What happens if the fossils were damaged during the journey? Dr Tan said: “Usually, it’s just cracks. Just glue back la!”

Once in Singapore, it then took about a week for the professionals from Fossilogic, a US-based fossil preparation and mounting specialist, to mount the sauropods in the museum, he recounted.

High price to pay for private ownership?

Yet, could dinosaur displays at public institutions like Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum become rarer amid private money being thrown at sought-after, almost-complete specimens like Apex, Stan and Big John?

After all, not many museums have the financial clout of multibillionaires like Mr Griffin.

Will this then deprive researchers of more specimens to study, document and annotate our world’s rich natural history, given that more pieces in private hands may be kept just that - private?

It’s an argument that has raged between academia and private collectors for decades now, and will not be resolved any time soon.

Dr Tan, for one, wondered what is to stop current or future buyers of dinosaur fossils from denying access to researchers.

“If I own a dinosaur, I can sell it the next day if I want to,” he said. “And if the next purchaser doesn’t want the dinosaur to be available ... keeps it in a warehouse and never shows it to anyone again. Then how?

“At least the museum is committed to (maintaining) the specimen for generations to come,” the professor said.

Carthage Institute of Paleontology’s Thomas Carr was more scathing in his review of the trade: “I would be very happy if the market stopped tomorrow.”

He explained that researchers are losing data - “the dinosaurs are the data” - and the only means of knowing about the true history and biology of these animals.

“When they are just sold off and become someone’s object art in their home, it really hurts science in a very measurable way,” Professor Carr said.

To break out of this seemingly endless debate, local fossils aficionado Calvin Chu posited a different perspective.

He shared how collectors like himself worry about what happens to their collections when they pass on. “Our children may not be very interested in them.”

But such collections shouldn’t then be thrown aside and ignored.

Instead Mr Chu said: “Having that track record of goodwill and collaboration on both sides, I think, creates that natural feedback loop for the fossil collector, at the end of (his or her) years to maybe donate their collection within a museum setting.

“That could be a way to bring the value back into the hands of public institutions.”

Catch our two-part documentary series Bones of Contention, which formed the basis of this interactive.