Meet the family repairing Singapore's watches and heirlooms for three generations

Like his late father, 65-year-old Willie Quek has dedicated his entire life to watchmaking. With his children and their spouses on board, what’s next for The Watch Specialist’s Clinic in Serangoon Gardens?

The Watch Specialist's Clinic's Willie Quek (centre) holding his grandchild, with his son Gabriel (right) and daughter-in-law Huan. (Photo: Joyce Yang)

It has been said that people don’t repair things anymore, but that just isn’t true at The Watch Specialist’s Clinic in Serangoon Gardens. Here, the Queks have their hands full by opening time at 10.30am even before their “father boss” arrives.

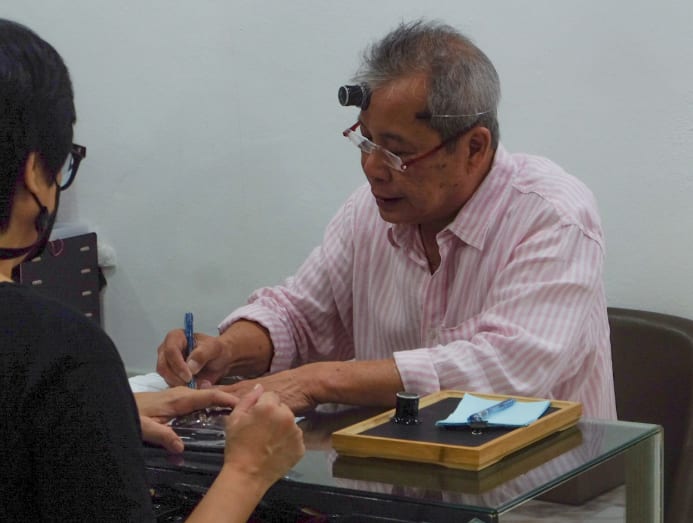

By “father boss” they mean Willie Quek, the 65-year-old custodian of his family’s legacy in watchmaking. He shuffles between the technicians and customers, diagnosing the ailments of their timepieces with a loupe around his neck like a doctor with a stethoscope.

“He wanted all of us to wear lab coats at first, but we refused to. So he was quite annoyed,” said his daughter Rebecca.

“TO BE A SPECIALIST, YOU MUST KNOW EVERYTHING”

As a young boy, Willie was intrigued by how minuscule parts could come together to tell time and thought: That’s something to pick up. He started repairing watches at his father’s workshop at seven and quit school to do it full-time at 15.

“Once I see the watch, I know how to fix it. I have this inborn ability,” he beamed.

Given his family’s circumstances then, a diploma in watchmaking was off the table. The only way to Switzerland was through a sponsorship. So, in 1975, he wrote to Rolex Singapore for a job. The interview was a day-long; he repaired a manual watch in the morning and an automatic one in the afternoon. Despite his best efforts, he was only offered the role of a Grade 3 technician. A beginner’s white belt in taekwondo terms.

It paid only S$250 a month, but Willie took it without question. He spent the next five years proving himself not only as a technician but also a mentor to junior staff – a figure few and far between in his industry.

“In our trade, the old people are very selfish. But we cannot blame them. Their mentality is that if I teach you, I am finished. To me, if I don’t teach you, I cannot go one level higher.”

When he resigned in 1980, his service manager likened his departure to losing a left arm. The head of Rolex Singapore at the time opposed his decision. But Willie was unstoppable in his pursuit of mastery.

“To be a specialist, you must know everything. Other people may say (my job at Rolex) was easy. But when you’re already stagnant, you don’t enjoy going to work every day.”

But perfection is something that perpetually recedes from a craftsman’s grasp, and so the next two decades took Willie to Transmarco, The Hour Glass and Dickson Watch & Jewellery, which flew him to Switzerland for the first time in 1988.

His longest stint was 10 years at Sincere Fine Watches, during which he revived the Anglo-Chinese School’s clock tower along Barker Road. It had been defunct for 20 years then, and his boss was an old boy.

“It was a really painstaking project. I had to fabricate the parts because the clock was damaged by students. Some parts were missing, which was why nobody wanted to take the job. It took me six months to finish.”

During the 1990s, his Midas touch also reversed the aftermath of a flood in Shenton Way. Back then, POSB’s safe deposit boxes were located in an underground facility that was prone to flooding, and one such box happened to contain a Patek Philippe when it poured.

Back then, the luxury brand in Switzerland quoted 35,000 CHF (S$57,712) for restoration, but Willie did it for just 15,000 CHF. Later, it reportedly fetched a whopping US$500,000 (S$674,000) at an auction.

“It’s not easy to sell a watch at an auction. They check everything – history, originality, and even parts I’ve changed and fabricated must meet the Swiss standards. But the auction house saw nothing different. It was the best work I’d ever done.”

By 2000, Willie was told “nobody in Singapore can interview you” by The Swatch Group. Instead, he was screened by seven factories in Switzerland – the likes of Breguet and Omega – and knocked it out of the park. When he was made service director, he had 25 years of professional experience and 10 diplomas under his belt.

This was his final stop before continuing his father’s legacy, which had come to a standstill when the latter passed away in the 1980s. Lee Ann Watch Dealers was succeeded by Quality Time in 2004, which made a home along Lowland Road for seven years before relocating to Maju Avenue as The Watch Specialist's Clinic.

THE WATCHMAKER OF SERANGOON GARDENS

“I think in Singapore, the workshop with the most machines is this,” said Willie, showing me the tools of the trade he inherited from retired watchmakers in Switzerland. I was told they don’t make them like these anymore.

Compared to their modern counterparts, which use CNC (computer numerical control) systems, these are more laborious to operate. But they allow him to fabricate individual parts from scratch – something large factories wouldn't re-programme their machines to do.

Bespoke services aside, customer service and a religious adherence to Swiss standards were cited as reasons why regulars have trusted the Queks for up to 30 years. In repair, every watch is stripped entirely, not partially. The finished product comes with a two-year warranty and one round of maintenance in the next five years.

“Nobody will take pictures and show them to customers. For us, every piece we take picture. No hanky panky. When we say 100 per cent service, this is the way. No shortcut."

Some go to them to restore family heirlooms or undo damages caused by other technicians. Others come knocking in hopes of a wallet-friendly quotation.

With Willie's help, one such customer saved S$10,000 on servicing a 5104P from the Patek Philippe Grand Complications series. It was a rare timepiece with hundreds of parts, and only “father boss” could do it. But it was “the most stressful two weeks” for Rebecca and gang, who had to maintain optimal conditions for him to work. For two weeks he lived in the workshop, sleeping in the day and working through the night.

“As long as I don’t need a break, I don’t even feel hungry. Only when I need to smoke, then I smoke. Other than that, eating is not important.” Willie said.

I asked him if it was challenging and he replied: Everything is difficult until you know it’s easy.

THE THIRD GENERATION OF CRAFTSMEN

What was it like to be raised by a watchmaker? For Rebecca, being surrounded by gears and wheels meant she couldn’t unsee watch parts when racing Tamiya cars with other children.

“I’m actually comforted by the smell of the chemicals because it’s just been around this whole time,” she said. But the 33-year-old never developed an interest until she left the civil service in 2021. In fact, her husband Chi Weng came on board four years earlier.

Meanwhile, watchmaking grew on her brother the way it did on their father – as a young boy.

“I used to watch my father fixing these little wheels and screws, and I was fascinated by all these tiny movements,” said Gabriel.

The 30-year-old had graduated from the Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Educational Program (WOSTEP) – Willie’s alma mater – where he was one of seven students cherry picked from over 40 applicants. By 2021, both Gabriel and his wife, Huan, were working full-time at The Watch Specialist.

“I was very happy that at least (the family business) can go to a third generation. Not many of my watchmaker friends have this opportunity.”

But working with family has its challenges. Change, even when championed by people you trust, can be scary. Willie was initially reluctant to move to Maju Avenue, fearing that being on the second storey of a shophouse would put them out of sight and mind.

“It took him a while to realise that customers come from online and word-of-mouth. You don’t walk around with a S$20,000 watch and say, I’m just gonna go into this shop and ask them to fix my stuff,” said Rebecca. (Willie does not seem convinced, and had earlier shown me a gigantic clock he plans to hang outside the shophouse.)

Working as independent watchmakers came with challenges that technicians in factories rarely contend with, said Chi Weng.

“At the agent, if you drop something, you can just replace it. Here, if you drop it, you’re screwed."

Replacing a missing part costs time and money, if they can even find that one elusive part of a 1950s vintage watch.

For the same reason, Gabriel has no official manuals to follow. Instead, he counts on loose references he finds online and fills the gaps with his watchmaker’s sense. It is both an art and a science.

“When I work on something new, it’s about studying the mechanism and how it works. I may take a longer time if it’s my first time, but to dismantle a watch, put it back, and see it working motivates me,” he said.

Restoration isn’t the most lucrative, but the Queks pride themselves on doing what others out there can’t. For Rebecca, seeing her customer's expression change when a sentimental timepiece is ready for "discharge" makes it all worthwhile. But that isn’t the best part of the job.

“Being able to see my family is. If anything happens in the end and we don’t do it anymore, I’d be glad that I got to hang out with my dad and spend time with him,” she said.

Willie’s dedication to his craft is enormous, and it seems almost inappropriate to probe when “father boss” would be retiring. When I did, Gabriel’s answer did not surprise me one bit.

“He always tells us and his customers that he will never retire from this job until the day his eyes or hands start to fail him. As long as they are good, he will continue.”