commentary Commentary

Commentary: The People’s Republic of China at 70 – reforms, achievements and challenges

Understanding China’s history can provide a useful guidepost for future Chinese decision-makers facing an uncertain future, says the NUS East Asian Institute’s Bert Hofman.

A heart-shaped Chinese flag installation ahead of the 70th founding anniversary of People's Republic of China is seen on a street in Shanghai, China, Sep 26, 2019. (Photo: REUTERS/Aly Song)

SINGAPORE: On Oct 1 this year, China celebrates the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

A central part of this celebration focuses on the country’s success in economic development and poverty reduction. Indeed, by next year, China hopes to celebrate the elimination of absolute poverty.

This momentous occasion is a good time to reflect on China’s journey over the past 70 years for three reasons. First, in getting the historical record right. This record is still shifting despite many volumes already devoted to the topic.

Second, understanding the basis for China’s success will guide China’s future reforms—understanding the path travelled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers‘ future plans.

Third, China now also positions itself as an example for other countries. China’s presence in the world economy, as investor, destination for exports, and increasingly innovator and provider of ideas should increase the need to understand its development journey.

READ: Commentary: The Hong Kong rain on Beijing’s parade as China turns 70

CHINA’S ACHIEVEMENTS

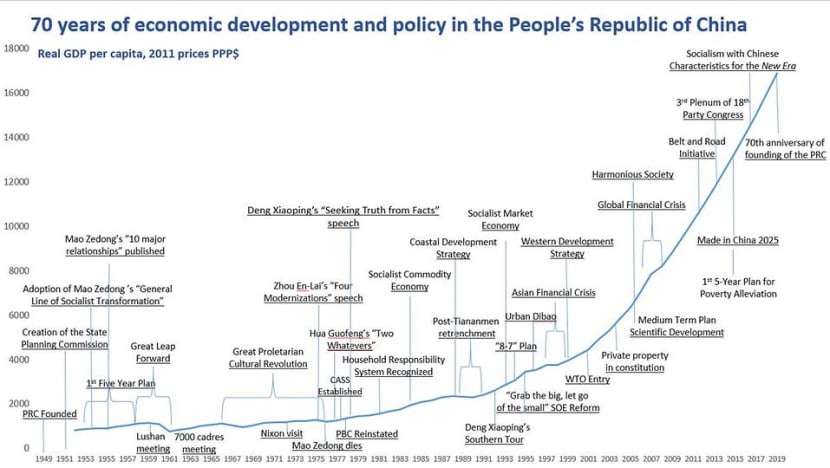

At the time of the founding of the People’s Republic, China was among the poorest countries in the world. Its per capita income was, at a little over US$700 (in today’s prices) barely 5 per cent of that of the United States then.

Though no official poverty statistics exist from that era, poverty at the World Bank’s extreme poverty line likely affected more than 95 percent of its population.

China made progress in those early days. Between 1951 and 1977, consumption per capita increased by some 50 per cent, according to national accounts data in the Penn World Tables.

This, despite the disastrous Great Leap Forward, which eventually caused an economic collapse of almost a third of its GDP.

Despite the disruptions of the Great Cultural Revolution, which practically halted university education, human capital as measured by the years of education enjoyed by the working population also more than tripled, from a paltry 1.3 years on average in 1950 to almost four years by 1980.

The World Bank’s 1981 study Socialist Economic Development records:

Despite slow growth of the average level of consumption, China’s most remarkable achievement during the past three decades has been to make low income groups far better off in terms of basic needs than their counterparts in most other poor countries.

Nevertheless, by 1978, the onset of the era of Reform and Opening Up, China was still very poor. Almost 90 per cent of its population lived in absolute poverty, its share of the world economy barely 1.5 per cent, and its economy was predominantly agricultural, rural and closed.

Forty years of reform turned China into the second largest economy in the world, the largest manufacturer and exporter, and the second largest spender on Research and Development. Six out of 10 Chinese now live in cities.

China will likely complete the journey to become a high-income country in the next decade, and will practically eliminate extreme poverty by next year.

Per capita income in constant dollars rose 25-fold, from US$308 in 1978 to US$7,329 in 2017; and more than 800 million people, so far, have escaped poverty, according to World Bank numbers.

THE FIRST PHASE OF REFORMS: CHINA’S OPENING UP

To a large extent, China’s success in reducing poverty can be attributed to the sustained rapid economic growth unleashed by reform and opening up after 1978.

Deng Xiaoping famously said:

Poverty is not socialism, not communism.

Deng kicked off reforms in a famous speech from 1978 titled “Emancipate the mind, seek truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future”.

Though it quoted Mao Zedong, the speech was a major departure from Maoism – a shift away from class struggle to economic development, from ideology to the emancipation of the Chinese mind by learning from others.

China’s reforms followed prescriptions mainstream economists would recommend. The country opened up to foreign trade and investment, alongside new ideas on economic management.

It also liberalised prices, diversified ownership and allowed the private sector to flourish, strengthened property rights, and invested in infrastructure and people.

Relative macroeconomic stability allowed high savings to be turned into high investment and rapid urbanisation, which enabled rapid structural transformation and productivity growth.

That summary, however, obscures the importance of the incremental and pragmatic character of China’s reform process. In Chinese, that approach is captured in the phrase “crossing the river by feeling the stones" often ascribed to Deng, though it was another party leader Chen Yun who said it.

Deng’s own “it does not matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice” which he first used in 1962 after the Great Leap Forward, became the credo for pragmatic reformers - doing what works.

Within this broad guidance from the leadership, reforms were implemented experimentally, often starting in a few regions, expanding nationally only upon proven success and taking into account development level and implementation capacity.

Hence, in place of a pre-set formula for development and shock therapy, room for the country’s own institutions and growth path to be gradually identified was provided.

READ: Commentary: Copycat no more? China’s emergence as a global innovator

Alongside, local officials were incentivised to succeed in implementing this reform agenda - their performance evaluation depended on success of their region. “Directed Improvisation” is what Singapore professor Ang Yuen Yuen has astutely termed China’s idiosyncratic path.

Competition among localities in attracting investment created good conditions for growth.

Political reforms, within the Communist Party, reinforced economic reforms. The introduction of age limits brought younger, more reformist cadres into the leadership fold, whereas term limits and collective decision-making limited government discretion, which in turn boosted investor confidence in reforms.

The first phase of China’s reforms, roughly from 1978 to 1993, were market-seeking reforms — seeking ways to build the market, first in agriculture, then in small-scale industry and then in urban areas and industries.

The Tiananmen tragedy in 1989 interrupted reforms, but they were rekindled by Deng Xiaoping during his “tour through the South” in 1992, which made clear that even though political reforms were not in the books, economic reforms were there to stay.

THE SECOND PHASE: MARKET BUILDING

The second phase of reforms, from 1993 to around 2003, or the Zhu Rongji years, were more outright market-building reforms.

The 1993 Third Plenum of the 14th Party Congress Central Committee had declared the socialist market economy as the prevailing system in China. This was the first time the term “market” was used to describe China’s system.

The 1993 Plenum’s decisions contained many features of China’s economic management today: The tax-sharing system, a modern central bank capable of designing and implementing monetary policy, and policy banks to relieve commercial banks of their policy function.

It also initiated state-owned enterprise reforms, which started in earnest after the Asian Financial Crisis under the banner “Grab the big, let go of the small”.

READ: Commentary: The Greater Bay Area, China's new and improved model for growth

China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001 locked in market reforms, and made China the production platform of choice for Asia’s supply chains.

Exports surged, and growth, driven by productivity increases unleashed by reforms, surpassed 10 per cent per year, until the Global Financial crisis cut this short.

THE THIRD PHASE OF REFORMS: MARKET ENHANCING

In the third phase of reforms, Chinese authorities increasingly sought to enhance the market.

Market-enhancing reforms came in two forms: First, the rapid expansion of social protection and insurance — pension, healthcare and welfare policies, among others, and a sharp reduction of taxes burdening famers.

Second, industrial policy returned to the scene. The 15-year Long-term Plan for Science and Technology laid the basis in 2006 for China to make the move from a labour intensive manufacturer of low value added goods to an innovative industrial superpower.

The practical translation of this notion became Made in China 2025, the controversial plan which lies at the core of the trade dispute with the United States.

READ: Commentary: Trump is serious about US divorce from China

Furthermore, state-owned enterprises made a return. The economic stimulus implemented after the Global Financial Crisis gave them a new lease of life, and while the 2013 Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee had assigned a decisive role for the market, it also designated state-owned enterprises a leading role in China’s economy.

READ: Commentary: The incredible resurrection of state capitalism in China

What had also returned was ideology. The Chinese Communist Party’s 2013 Communique on The Current State of the Ideological Sphere reminded all that China would not become a western liberal economy, nor would it make concessions to the Communist Party’s leading role.

At the same time, the Party’s anti-corruption campaign meant to ensure it remained fit to govern China.

The 2017 19th Party Congress confirmed the new policy directions: Market-based allocation, a dominant role for public ownership, and a strong emphasis on industrial policies and science and technology to achieve the goals of the “first phase of the New Era (2020 to 2035)” of socialist modernisation.

Meanwhile, China abolished term limits for the highest office in the country, and “Xi Jinping Thought” became part of the Party and country constitution.

CHINA’S FUTURE OUTLOOK

China is well on its way to becoming a high-income country. At the same time, its level of income is only one quarter of the average OECD country.

While the days of double-digit GDP growth have passed, China still needs relatively rapid growth to achieve its centennial goals.

Sustaining rapid growth has become harder for China, now that surplus labour from the countryside is almost exhausted, demographics no longer provide dividends, and the marginal returns on capital are likely to decline.

READ: Commentary: China has been secretly struggling to stabilise the yuan

READ: Commentary: China’s chief conundrum - how to look after the world’s fastest ageing population

The 2013 Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress and the Secretary General’s report to the 19th Party Congress reflect the leadership’s understanding that China’ growth will have to increasingly rely on productivity increases and innovation.

Productivity growth has been lagging since the Global Financial Crisis — and not just in China.

Within China, though, the relative importance placed on state-owned enterprises is not helpful, as most evidence suggest they are less efficient, in part because even inefficient state-owned enterprises do not go bust.

Furthermore, there is evidence that a large presence of state-owned enterprises in a sector discourages the entry of private firms — yet entry of new enterprises is key to innovation. Indeed, there is no high-income OECD country with a large share of state-owned enterprises in the economy.

READ: Commentary: In the eye of a trade war storm but China still takes the long view

A second headwind for future growth comes from the trade dispute with the United States.

Both sides will need compromise to reach a deal, but any enduring solution to this dispute will require further reforms in China - to strengthen institutions that will make China’s mixed economy work, further opening up of its markets, and acquiring the technology, managerial talent and ideas to catch up with more advanced countries.

READ: Commentary: Fighter jet sales to Taiwan and the complex US-China balance of power

Further opening up will also spur competition among its enterprises, which in turn will entice those to innovate and increase productivity.

Finally, China would do well to support reforms of the international trading system — a system of which it has been a principal beneficiary.

Bert Hofman is Director of the East Asian Institute at National University Singapore.