Commentary: How the Easter Sunday bombings reshaped Sri Lanka’s political landscape

The Easter Sunday attacks have greatly dented the government’s likelihood to get re-elected in the upcoming presidential poll, says Institute of South Asian Studies’ Roshni Kapur.

The Easter Sunday attacks in Sri Lanka killed 258 people (Photo: AFP/ISHARA S KODIKARA)

SINGAPORE: Sri Lanka’s political landscape is fragile than ever - with frequent protests, no-confidence motion and a dysfunctional government.

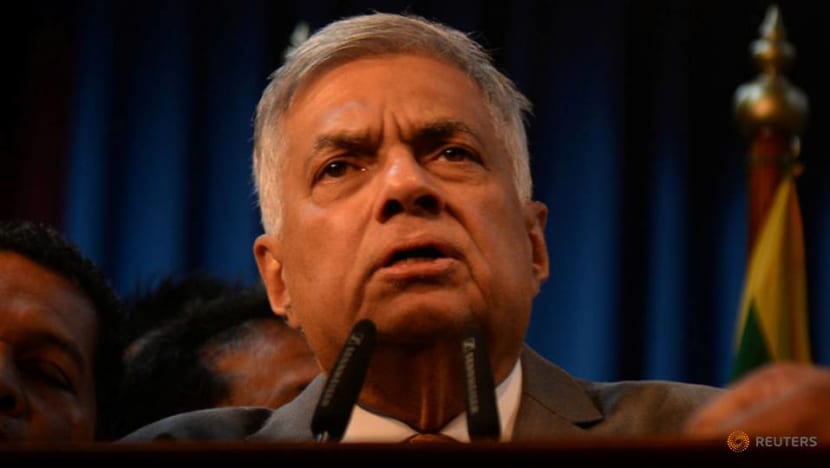

Elections Commission chairman Mahinda Deshapriya announced earlier last month that presidential elections will be held between Nov 15 and Dec 8. Although the nominees have yet to be confirmed, both President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe may contest for the presidency.

The chances of either of them winning the presidential elections are, however, slim.

The two leaders have been at loggerheads since last year on a wide range of issues, but the Easter Sunday bombings in April have aggravated their differences such that there are now calls for both to resign.

ANGER AT BOTH LEADERS

Supporters, including the two men’s party members who previously backed them, are angry at the two leaders for failing to take appropriate measures to stop the Sri Lanka Easter bombing that killed at least 250 in April.

United Nation Party’s Urban Council Chairman Rehan Jayawickreme in a public letter had asked Wickremesinghe to step aside.

The opposition has capitalised on these developments. Early this month, opposition group the People's Liberation Front (JVP) moved a no-confidence vote against the government on grounds that the ruling coalition ignored vital intelligence reports that could have prevented the Easter Sunday bombings.

The motion received support from Sri Lanka Freedom Party and the Joint Opposition who voted in favour of the motion.

The onus of the Easter Sunday attacks has fallen largely on Sirisena’s head since he is the Commander-in-Chief and Minister in Defence.

Senior officials have accused him of being privy to the Easter attack warnings. Suspended police chief Pujith Jayasundara submitted a petition to the Supreme Court indicting Sirisena of failing to stop the attacks.

The Parliamentary Select Committee, formed to probe into the Easter Sunday attacks, had also found evidence suggesting Sirisena had failed to act on prior warnings.

Wickremesinghe’s United National Front voted against the motion but acknowledged that the government failed to take appropriate measures.

HIGHER COMMUNAL TENSIONS

Following the Easter bombings, communal tensions in Sri Lanka have ratcheted up. Hate speech by nationalists has fuelled anti-Muslim violence.

Muslim-owned shops and houses were attacked and destroyed. Curfews had to be imposed - which were later lifted but re-imposed on several occasions.

The pardoning of the General Secretary of hardline group Bodu Bala Sena Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara despite his inciting of anti-Muslim violence has aggravated the already-fragile situation.

Sri Lanka’s economy, especially the tourism sector, has been badly hit after the attacks. Sri Lanka, despite being Lonely Planet’s best country to visit in 2019, saw a massive drop in tourist arrivals.

Hotel occupancy plummeted by 85 to 90 per cent as compared to before the attacks and news reports suggest holiday beaches, restaurants and shops have been close to empty.

READ: Sri Lanka's debt problem wasn't made in China, a commentary

READ: Deserted beaches, empty rooms: Sri Lanka tourism takes a hit after bombings

While the government recently announced that it will reduce the price of aviation fuel, embarkation and ground handling fees for six months at Colombo airport in an attempt to boost tourism, it is uncertain whether these measures can be effective.

It’s no wonder that the people of Sri Lanka are angry at their leaders.

LEADERS’ DEMISE STARTED LONG AGO

The leaders’ demise arguably, however, started long ago before the Easter bombings.

President Sirisena’s legitimacy has been called into question after a series of miscalculated moves during last year’s political crisis in which he dismissed Wickremesinghe and dissolved parliament, which plunged the economy into crisis, depreciated the rupee and damaged investor confidence.

In December, Sri Lanka’s courts opened the way for potential impeachment against the president as they ruled that his dissolving of parliament was unconstitutional.

He was then compelled to reinstate Wickremesinghe to prevent jeopardising his own political career.

Meanwhile, public support for Wickremesinghe plummeted ever since his alleged involvement in the Central Bank Bond scam that had citizens questioning the government’s transparency and competence, and perpetuated the image that corruption is rampant in Sri Lanka.

WATCH: Conversation with Sri Lanka's Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe

In the upcoming presidential elections, however, Wickremesinghe could have gained some sympathy votes for emerging as a symbol of democratic norms and values after last year’s political crisis when he was unconstitutionally dismissed by the president.

LEADERS FACE A STRONGER CONTENDER

These developments have created an opening for a contender from opposition leader, and former Sri Lanka president, Mahinda’s Rajapaksa clan.

READ: Sri Lanka's crisis of leadership opens space for nationalist Rajapaksas

While Mahinda Rajapaksa is unable to contest as a presidential candidate due to the constitutional limit of two terms, his brother, defence chief Gotabaya Rajapaksa is planning to run.

Gotabaya is popular among many Sri Lankans for his role in winning the 26-year Sri Lankan civil war that ended in 2009.

After the Easter Sunday bombings, Gotabaya began to project himself as the type of leader the country needs to rebuild the intelligence system and stop rising Islamist extremism.

His narrative has garnered him strong support from the Sinhalese-Buddhist majority.

But, Gotabaya has several challenges ahead of him: First, his dual citizenship, which many claim is an obstacle to him holding office in Sri Lanka. He claims that it is in the process of being renounced.

Second, the number of court cases in the US against him including allegations that he had ordered the murder of newspaper editor and torture of a Tamil detainee.

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Regardless who the people vote for, if a new government is elected, there is no certainty of what domestic and foreign policies it will adopt.

In a worst-case scenario, the next government may halt the current transitional justice mechanism, despite it being the most crucial aspect of the current government’s reform agenda.

Already, Mahinda Rajapaksa rejected the UN Human Rights Council’s recommendations on setting up a mixed court consisting of both local and international judges from the beginning.

Discontinuing the transitional justice process would deny war survivors access to reparations, truth-seeking and tracing their missing family members. It would also forgo any prospects for institutional reform and gender and minority justice.

In 2015, there were genuine efforts to cooperate with international institutions to advance reconciliation and truth in the aftermath of a protracted civil war.

Although there have been delays on reforms, the government managed to make some progress to pass bills on setting up the Office on Missing Persons (OMP) and Reparations office.

What Sri Lanka need now is strong leadership and maturity. Leaders should continue with the ongoing investigations, strengthen its intelligence network and surveillance capabilities to curb radical extremism and promote interfaith dialogue between the different communities.

Elections may be only a few months away, but there is still time for leaders to try to put things in order.

Roshni Kapur is a Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies in the National University of Singapore where she specialises in conflict resolution, peacebuilding and transitional justice in Sri Lanka.