commentary Commentary

Commentary: Why it doesn't matter who wins Jakarta come Apr 19

Between Ahok and Anies Baswedan, the battle lines for Jakarta have been drawn. But the long fought contest for the soul of Indonesia is what we should watch instead.

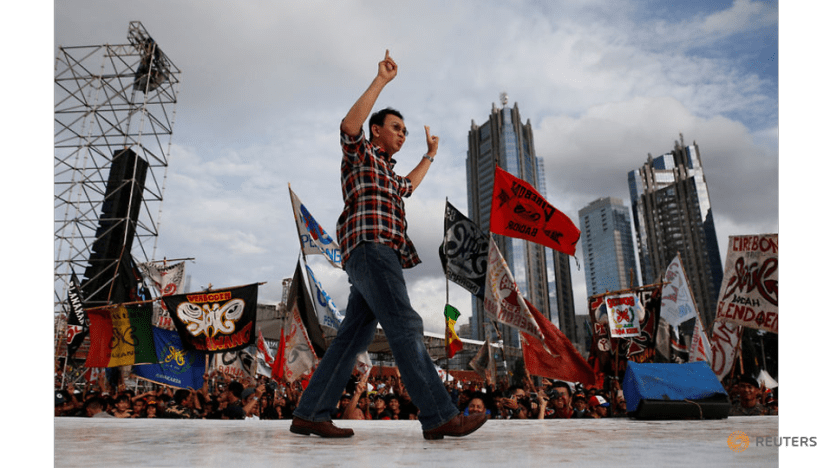

Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, known as Ahok, waves to the crowd as he attends a music concert ahead of this month's elections in Jakarta, Indonesia February 4, 2017. REUTERS/Darren Whiteside

It was no surprise that the first round of the gubernatorial election held on Feb 15 to elect the Governor of Jakarta to a five-year term proved inconclusive. Incumbent governor Basuki Thahaja Purnama – popularly known by his Hakka moniker Ahok – and his running mate Djarot Saiful Hidayat led in a race widely viewed as a litmus-test of Indonesian pluralism with his competitor not far behind.

Ahok garnered almost 43 per cent of the vote, despite an ongoing blasphemy case and huge protest rallies by hard-line Islamists, who attacked him on both racial and religious grounds.

His rivals, former Education Minister Anies Baswedan trailed slightly behind with 40 per cent and Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the eldest son of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, came in a distant third with just 17 per cent. With no candidate securing more than 50 per cent of the vote, Ahok and Anies, the top two finishers will face off in a second round this Wednesday (Apr 19).

If Ahok prevails, he will become the first elected Chinese Christian governor of Jakarta.

Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, nicknamed "Ahok", leaves the stage after meeting with supporters while campaigning for the upcoming election for governor in Jakarta, Indonesia November 16, 2016. (Photo: Reuters)

CHOICE BETWEEN PLURALISM AND HARD-LINE POLITICAL ISLAM

This has been a polarising election, and is not just about choosing the Jakarta mayor. The election has now become a larger choice between pluralism and the possibility of hard-line political Islam deepening its roots in the world's most populous Muslim nation. Ahok's rivals, Agus and Anies, wooed the support of hard-line Muslim groups like the Defenders Islamic Front (FPI). These groups believe that non-Muslims should not hold high office in Indonesia.

The latest polling for the second round of the up-coming Jakarta Gubernatorial by Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting indicates that Anies Baswedan has a slight edge at 47.9 per cent with Ahok at 46.9 per cent and undecided voters at 5.2 per cent.

A chronology of the Jakarta election shows Ahok clearly leading in polls prior to his ill-fated Al Maidah September 2016 speech to citizens of Pulau Seribu that went viral on social media. Between 45 to 47 per cent said they would vote for him. After the video went viral, the percentage of voters who said they would vote for him plummeted to 26.

Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly known as "Ahok", sits on the defendant's chair at the start of his trial hearing at North Jakarta District Court in Jakarta, Indonesia, Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2016. (Photo: Reuters)

This setback notwithstanding, by January 2017, Ahok’s polling numbers were trending up – a likely indication that for many voters, his performance as governor was the defining factor in their decision to vote for him not race or religion. According to Tempo, Ahok’s voters mostly vote for him because of his performance whereas many Anies voters say they vote for Anies because of religious belief.

No doubt, Ahok’s straight talking style grated Javanese voters who considered him course or unrefined. Yet, when I visited Jakarta in September 2016 prior to the Al Maidah 51 controversy, all the taxi drivers I spoke to stressed that while they did not like him, they liked his way of working.

Race and religion may be foremost on the minds of Indonesians after the video went viral, but once emotions settled, Jakarta citizens seem to value the tangible improvements to their quality of living Ahok has made. In his term as governor since 2014, Ahok has decisively resolved Jakarta’s perennial problems with floods. In the past, it would take a whole day before the floods would clear. Ahok’s flood alleviation schemes now mean that taxi would be able to return to work after three hours.

The Hotel Indonesia roundabout inundated by floodwaters in Jakarta on January 17, 2013. (Photo: AFP)

RACE AND RELIGION REARS ITS UGLY HEAD

Yet there is no denying that the fundamental issue in the Jakarta gubernatorial election is religion. Of course this not a new occurrence. After three decades of repression under Suharto’s New Order regime, Indonesia’s democratic environment has given Islamists the opportunity to openly and freely organize themselves, whether in demanding the establishment of Islamic law or even the institution of an Islamic State.

But democracy also provides countervailing balance to hard-line political Islam inclinations. The initial advocacy to amend Section 29 of the 1945 Constitution, meaning that all Indonesian Muslims would have to respect Sharia in its entirety, was stillborn when a motion in Parliament in early 2000 was rejected.

This did not deter Islamist parties PKS and PBB who withdrew their shariah demands but changed their strategy to push their agenda regionally and moved to legislate regional shariah bylaws. In the course of ten years, more than 60 local shariah regulations were ratified in various districts and cities including Aceh, Padang, Banten, Cianjur and Jombang. Not to be outdone, nationalist parties like Golkar and Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party (PD) have also supported shariah ordinances.

The imposed Islamic laws were intended to regulate three aspects of public life: First, to eliminate social crimes, prostitution and gambling. Second, to impose a requirement for Muslims to abide by ritual obligations like the reading of the Quran, attendance at Friday prayers and observance of the Ramadhan fasting month. Third, to necessitate the wearing jilbab or hijab for Muslim women when in public.

Indonesian students march in Malang city in East Java province on February 14, 2013 during an anti-Valentine protest that declared the day to be "hijab day" or "headscarf day". (Photo: AFP)

However, the emergence of hard-line Islamic movements in recent years, whether through promulgation of shariah laws or the materialisation of more conservative attitudes constitutes a new phase of the relationship between state, Islam and democracy.

True, sweeping democratic reforms post Suharto gave conservative Islamic hardliners space to spread their influence and gain political ground. It might have appeared to be the case. 42 out of the 181 political parties formed in the first two years after the collapse of the Suharto regime were Islamic political parties. New Islamist organizations also rose from the ground over the years, including the Indonesian Mujahidin Council (MMI), the Laskar Jihad, Front Pembela Islam (the Islamic Defenders Front), and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia.

Looser restrictions on freedom of speech by the Habibie administration allowed them to rally the ground for shariah, emphasising its political, social, cultural and legal dimensions. Islamist or Islamic-based political parties also worked in tandem with non-parliamentary Islamist movements to uphold the application of shariah.

However, public support for an Islamist agenda was not high and would erode over the years, at least on paper. By the 2014 national parliamentary elections, Islamic parties scored only 33 per cent of the popular vote, compared to secular parties which garnered more than 50 per cent.

WORRY TREND OF ISLAMIST WAVE

That is not to say that hardline political islam did not have a following, bubbling beneath the surface. Followers of more radical groups such as Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia and Front Hizbullah Bulan Bintang have gradually grown in strength. Jemaah Islamiyah leader Abu Bakar Baasyir’s Jamaah Ansharu Tauhid and his son’s movement Jamaah Ansharus Shariah also have some degree of appeal with Indonesian Muslims, to a lesser extent. But we forget that extremist Islam tends to rear its ugly head sporadically with disastrous tragedy – and the occurrence of terror attacks and bombings have only increased in recent years.

Indonesian policemen examine the site where a blast occured in Semarang. Three construction workers were wounded on Thursday after a small bomb exploded on Indonesia's Java island, police said. (Photo: AFP)

In a way, the seven million strong protest against Ahok over end-2017 was a reminder of the sway that hard-line Islam has over segments in Indonesia. The Front Pembela Islam leader Habib Rizieq Shihab's prominent direction of these events was deemed a victory for the Islamists over the moderate leadership of Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama, the two largest Islamic organizations in Indonesia.

The short outrage over Ahok’s comments belies a deeper seated influence political Islam has over Indonesian politics. It may be Islamist dogged pursuit or promotion of Sharia over many years. Cases of government corruption, the increasing cost of living and general disillusion of the effectiveness of government in raising the quality of life for Indonesians are easy targets, fodder for evidence of the drawbacks of a non-shariah system. For Islamists, democracy did not bring about stability and growth but disorder. If citizens wanted prosperity and order, then shariah was the answer.

Such perspectives are gaining wider acceptance. A survey conducted in October 2016 by the Centre for the Study of Islam and Society indicates that 78 per cent of Islamic teachers support sharia enactment in Indonesia with 77 per cent of respondents supporting Islamist organisations with a shariah focus. It is also not surprising that in the 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial election, Jokowi’s candidacy was attacked by rumours asserting that he was a Communist, a Chinese and worst, a non-Muslim.

Crowds shout slogans during a protest outside a Jakarta court where the trial of Jakarta Governor Basuki 'Ahok' Tjahaja Purnama is taking place. (Photo: AFP)

If Ahok is found guilty of blasphemy, the ruling has the potential to galvanise radical Islam and deal a setback for moderate Islam, which has traditionally characterised Islamic practice in Indonesia. Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, the two most pre-eminent Muslim organisations in Indonesia with their long tradition of Islamic moderation and the propagation of Islamic principles and values in line with Indonesian culture and local wisdom, would be cast as passive onlookers. Their public agenda of the compatibility of democratic values with Islamic doctrines will be further strained. Their role in promoting plural and moderate Islamic values in domestic and foreign policy will be conscribed.

Some say whether pluralism or radical Islam wins will be captured in the results of the Jakarta election on Apr 19. I believe it doesn’t matter. Because whoever wins, the capitulation of the largest moderate Islamic organisations in Indonesia to the Islamist wave is a worrying trend and should be observed closely. And this trend may be carried into the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections.

Associate Professor Leonard C. Sebastian is Coordinator, Indonesia Programme, S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University and Adjunct Associate Professor, Australian Defence Force Academy, University of New South Wales.