commentary Commentary

Commentary: Why Singapore is preparing to tap the brakes to slow COVID-19 spread

A variety of different combinations of interventions aimed at “flattening the epidemic curve” have popped up around the world, but time is needed for these to bear fruit, say the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health’s Hsu Li Yang and Natasha Howard.

People seen wearing masks at Chinatown, Singapore on Mar 11, 2020. (Photo: Gaya Chandramohan)

SINGAPORE: The world is coming to grips with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic that began last year in China and is now sweeping the globe.

Much is now known about this virus, indicating we are facing a threat the scale of which has not been seen since the 1918 influenza pandemic.

One other thing is also certain: Letting the pandemic take its “natural course” is not an option we should consider.

The main statistic driving action, despite the relative perceived mildness of most infections, is that approximately one in 20 confirmed adult cases will require mechanical ventilatory support, available primarily in hospital intensive care units.

If demand exceeds supply of this relatively scarce and inelastic resource, fatality rates will increase dramatically beyond COVID-19’s current estimated fatality rate of 0.3 per cent to 1 per cent, as will deaths from any other conditions requiring hospitalisation and intensive care.

IMPORTATION AND NEW OUTBREAKS LIKELY

No country will be completely free from the threat of SARS-CoV-2 in the short and medium term.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus will likely continue to circulate globally, perhaps becoming the fifth endemic human coronavirus, given that countries and territories are at different stages of the pandemic.

China may have eliminated the virus from large segments of the country, while several Asian countries - including Singapore and South Korea - have slowed or managed its national spread.

READ: Commentary: Why Singapore is better prepared to handle COVID-19 than SARS

READ: Commentary: The ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic could unfold

But Europe, North America and several countries in the Middle East are in the ascending phases of their epidemics, while African and South American countries are just starting to report cases.

That means China, Singapore and other places thought to be recovering from the spread will remain vulnerable to virus importation and new outbreaks that are potentially as severe as the first wave as more than 99 per cent of their populations have not yet been infected.

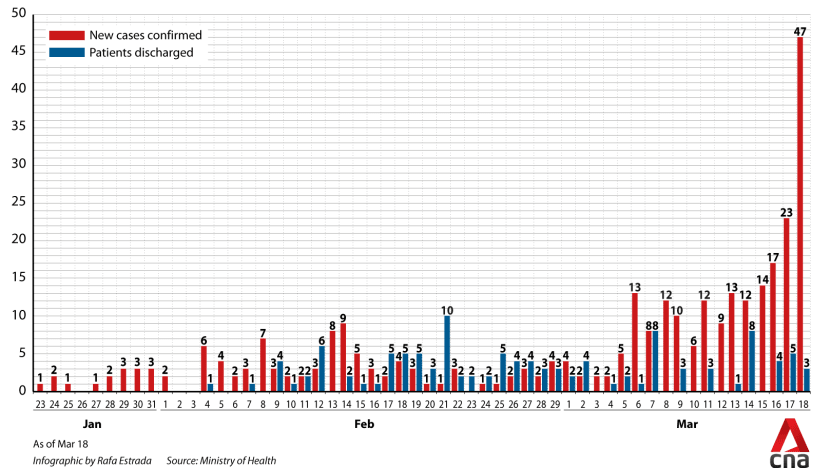

The spike of 17 imported cases in Singapore on Tuesday (Mar 17), with a further 33 on Wednesday, shows we must stay vigilant.

HOW TO MANAGE THE PANDEMIC

How can countries end or at least manage this pandemic? The answer lies in trying to convert a “tsunami” into multiple smaller and manageable “waves”.

In epidemiological terms, if the effective reproduction number “R” of SARS-CoV-2 is brought below 1 – i.e. each infected person infects on average less than one other person – the outbreak will be on a downward trajectory and transmission will end once “R” reaches 0.

If “R” remains just above 1, the local outbreak will spread more slowly and ultimately result in fewer persons infected – “flattening the epidemic curve” - thus not overwhelming the healthcare system.

Many experts believe that the coordinated interventions implemented by China, if contextualised and applied globally, would end the pandemic – a metaphorical “global reboot”.

These measures include locking down regions with uncontrolled community transmission (as China did with Wuhan and large parts of Hubei) to prevent exportation of cases; aggressive case detection and contact tracing, with prompt isolation and treatment of cases and quarantining of close contacts; strict social distancing that includes cancelling mass events, curfews, and shutting down public transport where necessary; and logistical support to the population affected.

READ: Commentary: Japan really needs to get cracking on coronavirus testing

South Korea, however, chose a different model. Even at the height of the epidemic in Daegu, the city was not locked down. Instead, testing was ramped up rapidly, including setting up make-shift test centres near areas with many infections and novel drive-through testing.

In just under three weeks, South Korea established a network of laboratories that could perform up to 20,000 tests a day, allowing for earlier diagnosis and isolation of cases, with mild infections isolated at home rather than in the hospital.

Other social distancing interventions were more restrictive, including school closures and cancellation of large events.

READ: Commentary: Explosion in COVID-19 cases - was South Korea just unlucky?

READ: Commentary: The perfect storm for a COVID-19 outbreak lies in North Korea

WORLD IS TRYING TO FLATTEN THE CURVE

What we are seeing around the world in the past two weeks is a variety of different combinations of interventions aimed at “flattening the epidemic curve” but time is needed for these to bear fruit.

Where there is already widespread community transmission, such as in parts of Italy or Spain, the interventions have resembled what occurred in Wuhan.

Virtually all countries and territories to date have also significantly stepped up travel restrictions – including Malaysia this week – aimed at reducing one source of infections.

Which particular intervention are more likely to work or which are redundant in terms of reducing “R” relative to their socioeconomic cost is dependent on the specific situation and health system in each country.

However, the more restrictive and self-isolating interventions will exact considerable socioeconomic costs and negatively impact closely inter-dependent countries and territories.

SINGAPORE MUST PREPARE FOR SPIKE IN CASES

What does this mean for Singapore?

Our country has thus far taken a relatively moderate approach to controlling the virus spread, focusing primarily on aggressive contact tracing and quarantining of close contacts of confirmed cases.

However, we must not become complacent. We must prepare for a scenario in which significant case increases threatens to overwhelm our intensive-care resources.

Such a scenario will require resolute implementation of more intrusive or liberty-limiting social distancing measures, as in China or Italy, to reduce “R” and achieve more manageable COVID-19 case numbers.

READ: Commentary: Three scenarios if the COVID-19 outbreak gets worse

READ: Commentary: Can vitamin C really help with your cold or even COVID-19?

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong referred to these reduction measures as the “extra brakes” in his address to the nation on Friday (Mar 12). Because such interventions are difficult to sustain, a plausible approach would be to ease off these interventions once containment is achieved, and reintroduce them, or “tap the brakes”, as needed - repeatedly if required.

This may be more acceptable and feasible than the alternative of an indefinite national lockdown to attempt a “reboot” to a COVID-19-free state.

INTERVENTIONS SHOULD BE GUIDED BY SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE

Countries are most successful in mitigating the spread when their interventions are guided by the scientific evidence.

In Singapore’s current situation where the majority of cases are imported, travel restrictions have been temporarily extended to all territories exporting cases even if official case numbers remain low.

Alternatively, closing schools – given the data suggest that children are not the main transmission drivers - would not be helpful to bring down “R” except as a general signal of the gravity of the situation.

Closing public transport or imposing curfews should only be done as a last resort in the context of a massive rise in unknown community clusters and deaths.

It is important to note that we will not know how well any approach, whether our current moderate social distancing, more rigorous but temporary brake-tapping, a full lockdown and reboot, or some combination can work to reduce “R” before its implementation.

READ: Commentary: COVID-19, the biggest crisis ever for Singapore’s aviation industry and Singapore Airlines

READ: Commentary: UAE fights COVID-19 while the rest of the Middle East drags its feet

Unlike a laboratory experiment, there is no way to reset and repeat interventions until we have definitive answers.

Epidemiological modelling will only generate a narrower range of uncertainties. Interventions have to be implemented in imperfect conditions. The nature of outbreaks is such that the effect of any intervention on case counts will only start to be evident one to two weeks later.

Additionally, case numbers remain inaccurate as over 80 per cent of infected people – especially children – will experience mild symptoms and may never be diagnosed.

Thus, countries that test extensively will detect more cases than those that do not, while countries with large numbers of deaths relative to cases, or that export cases, will have far higher proportions of infected but undetected cases.

GETTING READY TO TAP THE BREAKS

Our current approach in Singapore appears to be working and allowing a relatively sustainable balance between restrictions and normalcy.

However, we must be prepared to quickly implement more restrictive social distancing measures – at least as a means of national brake-tapping – should COVID-19 case numbers begin to increase significantly.

Hsu Li Yang is the Infectious Diseases Programme Leader and Associate Professor at the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. Natasha Howard is an interdisciplinary health policy and systems researcher with a dual Associate Professorship at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.