Medieval fencing cuts a common ground for fans from all walks of life

The modern-day ‘knights’ who take the sword-fighting stuff that you see in movies and role-playing computer games very seriously.

Mark Tan, 29, practises weekly at the Eurasian Association with PHEMAS. (Photo: Kelvin Chia)

It could be a fascination for swashbuckling movies, or a passion for playing fantasy genre PC games. Or it could be that sense of wonderment you get from reading Arthurian legends of chivalrous knights and their quests.

Whatever it is that got you interested in medieval swords and sword fighting in the first place, it is a very real form of martial art practised in Europe in the Middle Ages, said Rigel Ng, 24, an instructor and president of the Pan Historical European Martial Arts Society (PHEMAS), as he took out swords of various lengths from a bag.

He was speaking to CNA Lifestyle at the Eurasian Association, where he gathers likeminded individuals twice weekly to train and share knowledge of Historical European Martial Arts or HEMA for short.

Yes, the sword action that you see on TV and in the movies is being practised here in Singapore. And they do use swords. The steel stuff.

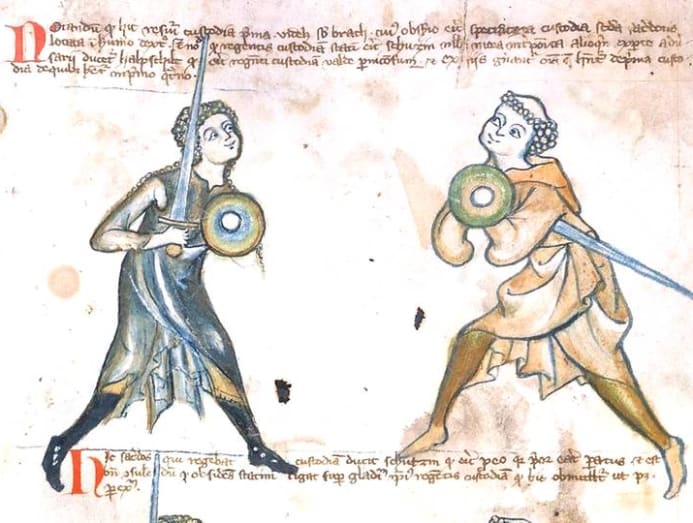

Martial art isn’t only about the wuxia genre depicted in Chinese fantasy books and films, or spirituality conveyed through Japanese kendo. Back in the 13th century, Europeans were thrusting, cutting and defending with blades and shields – except that they did it for survival and not wellness.

“It is interesting to hear that 90 per cent of the European population thinks that Europe didn’t have any forms of martial art,” said Ng. “They would have because they were fighting each other for about 500 years.”

CHOOSE YOUR WEAPON

Medieval sword fighting or fencing isn’t about hitting or stabbing the vital points on your opponent’s padded torso with a malleable thin foil. Instead, practitioners often start off with the messer, which Ng described as a one-handed, parang-sized sword.

As you get more proficient, you may be handed a buckler, a round shield that is no larger than a frying pan that commonly complements the messer. What good is a small shield? Plenty, explained Langley Qu, 35, an instructor at Bastion HEMA, as she sat down to talk about the martial art that Lucien Lee, her husband and founder of the school, got her hooked on six years ago.

“People think you must need a large shield to cover yourself properly. The answer is no. Bucklers were made small for ease of carry. Some have sharp edges that you can use to maim, so you essentially have two weapons in hand when you use it with the messer,” she said, adding that their size also made it possible to slip into the eye slit of the opponent’s helmet.

There’s also the longsword, probably the most quintessential weapon associated with medieval sword fighting. It is a formidable-looking, two-handed sword with a straight, double-edged blade and a straight guard that makes the sword look like a cross. You might recognise it as a weapon similar to what Jon Snow in Game Of Thrones uses.

Another single-handed sword is the rapier. It has a slender blade connected to, in some cases, a hilt designed to look like elegant swirls of metal; it doesn’t just protect the hand, it also adds to the sword’s aesthetics.

In some instances, the poleaxe may be added to the mix. It is essentially a long pole with a hammer on top. “It was the anti-armour weapon of the day,” said the 36-year-old Lee, who is also an instructor at Bastion HEMA. The couple picked up the sport while studying in Swansea, the UK, and had practised it for three-and-a-half years before returning to Singapore and starting the school two years ago.

“Other than learning how to fight with these weapons, there is also ringen, which is German for wrestling and is a big part of medieval sword fighting,” said Qu.

KEEPING IT REAL

The battle scenes that you see in movies such as Lord Of The Rings are often of epic proportions. Swords and axes clash, battle cries are bellowed, and the camera goes into slow-motion mode to capture the choreographed fight. Those movements may look dramatic on the silver screen but back in the Middle Ages, they’d probably get you killed.

In actuality, it wastes a lot of energy swinging your sword around during a battle.

“In actuality, it wastes a lot of energy swinging your sword around during a battle,” said Qu. The movies give you maybe 20 per cent of the truth." For instance, both the messer and longsword can each weigh from almost 1kg to nearly 1.5kg. Despite its slenderness, the rapier can tip the scales at 1kg.

The techniques and movements taught in HEMA clubs aren’t random. Most of what is imparted worldwide – not just in Singapore – is based on ancient treatises, the earliest of which was discovered in a German monastery in the 13th century.

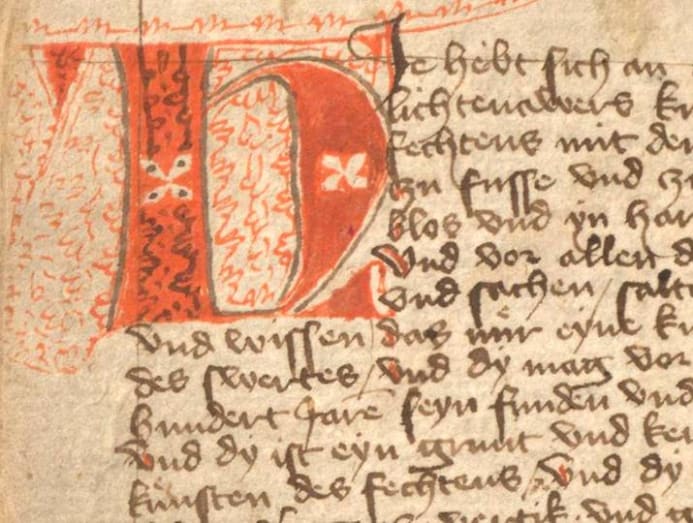

It was followed by the works of the 14th-century German master Johannes Liechtenauer. “Many wouldn’t consider what he wrote as a manual per se. A lot of sources say that he put the techniques into a poem,” said Ng.

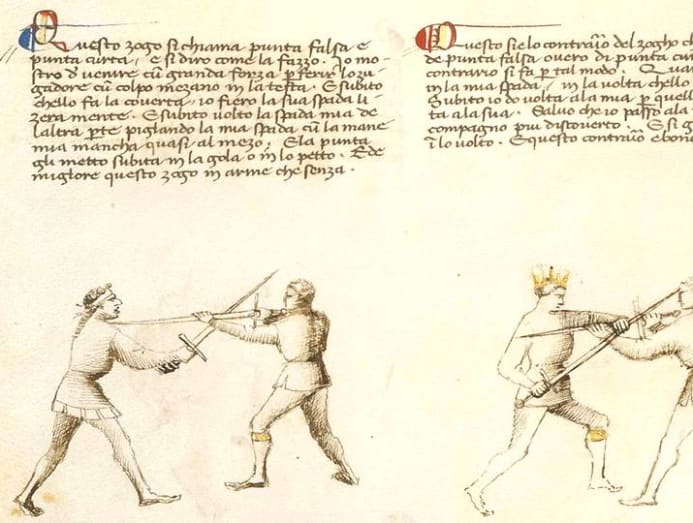

The next definitive treatise was by an Italian named Fiore Dei Liberi, written also in the 14th century, which he had compiled for his patron. “It wasn’t as cryptic as Liechtenauer’s but it still wasn’t as basic as a manual. For instance, Dei Liberi didn’t mention how to hold your sword,” said Ng.

Because the techniques are up for interpretation, Ng, who has been fencing for four years, said that medieval sword fighting is still evolving. “It’s like submitting your findings to a scientific journal. If your theory is not accepted by your peers, you research further before coming back to the ring with what you have and convince them.” In contrast, you don’t tweak what the master has passed down to you in most Asian martial arts, he said.

One thing was clear though. It was about upping your killing efficiency. “The plays consist about one or two moves because you wouldn’t want to drag it out. You want to make quick work of ending your opponent,” said Ng.

“But when you get to the late 15th century, the plays were five or six moves long. You get the feeling that it was a more sportified version of swordsmanship. There were also performances and tournaments in those days where people could see your prowess with a sword. But it was still less sportified than what we do today.”

Most of the people who come to the classes have played games that have realistic sword fighting, and are curious how it would look and feel in real life.

MEDIEVAL COSPLAY?

Just as the people who practised swordsmanship in the 13th century were an eclectic group, according to Ng, so too are the modern practitioners. In Singapore, there exists a small community of fewer than 50 active members, said Ng.

PHEMAS, which was founded in 2005, has about 20 active members. Owing to Singaporean co-founder Greg Galistan, the group has been convening in the hall at the Eurasian Association to practise and spar since its inception.

“The thing about the sword is that it’s such a cultural symbol of adventure and fantasy. Most of the people who come to the classes are MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) nerds who have played games that have realistic sword fighting, and are curious how it would look and feel in real life,” said Ng.

“You also have Japanese culture enthusiasts who are into kendo and kenjutsu. Even anime has some western influences like the one based on Joan Of Arc, a historical figure in France.”

Despite the element of role playing (knight in figurative shining armour, anyone?), Lee doesn’t consider medieval fencing as cosplay in the popular sense. “We’re not exactly cosplayers; we don’t dress up. We are trying to re-enact a certain kind of fighting system from the medieval ages."

Lee added: “But I think there are individuals who adopt a certain persona when they train because this is stuff you’re not going to use in your everyday life. Once in a while, everyone just wants to feel like a swordsman or knight. And we give them the chance and the space to do that”.

GIRL POWER WITH SWORDS

HEMA clubs’ propensity to attract men doesn’t preclude women from joining them. Qu, for one, is a female instructor. Of the 30 active students at Bastion HEMA, nine are women. In fact, they have just started running women-only classes this year.

“We had a German master Jenspeter Kleinau over late last year, and he said this shouldn’t be a macho sport,” shared Qu. “Women should be comfortable to join and women’s interest should be fostered, he said.

This shouldn’t be a macho sport. Women should be comfortable to join and women’s interest should be fostered.

But because there is a lot of contact and guys are stronger, women may feel a little uncomfortable or intimidated.” So they started offering women-only classes once a week, which aren't taught differently from the regular ones.

“The only difference is that women may not have the initial arm and wrist strength, and may not be so in tune with their bodies. When they come here, they learn to be mindful and intentional with their movements,” said Qu.

June Gan, who has been participating in the regular classes for close to six months, enjoys learning about medieval swordplay and how the techniques came about. "I've always been a bit of a nerd," said the 25-year-old, who works in sales and marketing. "I did a bit of riding when I was younger and archery at university, so I guess HEMA and swordfighting were just a natural progression."

MEET THE LION CITY KNIGHTS

With an unusual name like Gawain Chew (it is also the first name of King Arthur's nephew and a knight of the Round Table), it is evident that the 31-year-old executive, who specialises in intellectual law, is a fan of Arthurian tales.

"I have been fencing for about 17 months," he said. So dedicated is Chew to fencing that he started judo lessons recently. "A lot of what we do here is basically wrestling, so judo actually complements fencing," he said.

David Han, who is a martial arts enthusiast, has tried fencing and used to practise muay thai and boxing. He finds historical swordsmanship more practical than fencing. "When you read martial art-themed novels and they describe the swordplay, I can visualise the movements better after picking up HEMA," said the 38-year-old, who works as an IT software tester.

While most teens get their kicks from gaming, student Brendan Toh prefers to clash swords in person and not in a RPG computer game. The 16-year-old has been taking HEMA lessons since last October and loves it. "It’s a head rush! It’s competitive and yet, it’s also about strategy. It is interesting to learn about the very things that people hundreds of years ago were doing," he said.

HEMA practitioners may come from all walks of life but they share a love of swords. Mark Tan, for instance, is the proud owner of a longsword and rapier. The 29-year-old research assistant has been fencing for four years and has spent a few thousand dollars on his gear, including fencing mask, padded jacket and pants, and gloves.

"I probably have spent more than I should!" he laughed. "Most of the gear can only be bought overseas and sometimes, the shipping can cost more than the items."

Find out more about historical sword fighting at PHEMAS and Bastion HEMA.