Inside the women’s prison: Empathy, rigour and help to turn inmates' lives around

Prison officers are not only inmates' warders, but also a listening ear and source of counsel. CNA Insider gets an unprecedented look at life behind bars in Singapore's only women's prison.

The role of prison officers is evolving towards more rehabilitation – they go for courses to relate to inmates better and look out for the welfare of those under their charge.

SINGAPORE: The prison officer waited outside the room as the inmate spoke to her family. These opportunities, which come twice a month for prisoners, can be joyful or upsetting – this time, it was the latter.

When she came out, she was hysterical. “Her brother had passed away in his sleep the night before,” said Rehabilitation Officer 2 (RO 2) Nurul Hazirah Abdul Halim, 25, who knew that the two siblings were very close.

What added to the inmate's grief was that her family didn't ask for her to be allowed to attend the funeral. And RO 2 Nurul Hazirah, her personal supervisor, was there to console her.

Being a source of comfort might seem a job for counsellors, rather than prison officers. But the latter are now spending more time engaging inmates meaningfully, as CNA Insider found out after gaining an unprecedented level of access to Singapore’s only women’s prison.

Institution A4, formerly known as Changi Women’s Prison, houses approximately 1,200 inmates, one tenth of the prisoner population.

And at the heart of it all – from the programmes and workshops for inmates, to the counselling and family visits – are the all-women team of approximately 90 officers running the prison.

They are not only warders but also a listening ear, both for inmates unburdening their angst about personal problems as well as for more mundane requests that range from changing cells to changing the food boxes.

The role of the guard has been evolving more towards inmate rehabilitation, and for the officers it means adding more tools to their repertoire – beyond the batons and pepper foam that are a part of their standard carry – like empathy.

Said Assistant Superintendent of Prisons 1 Evelyn Tan, 25: “While we empathise, it’s not because we pity them, I think. It’s more because we want to understand what they’ve been through so that we can help them to be better."

And the inmates typically have been through a lot to end up in jail, the officers note.

WHY THEY ARE THERE

Relationships, alcohol and traumatic experiences like sexual abuse were some of the starting points for many female inmates. RO 2 Nurul Hazirah said:

“Sometimes when you speak to the inmates, and you find out they’re here because their husband forced them to take drugs and all that, as a woman you get very angry.”

Among young inmates, especially those from broken families, it often started with peer pressure and the need for attention and love.

“When they found a group of friends who were willing to like, ‘let’s do this and stuff’, then they felt accepted,” said Sergeant 3 Alysa Naqeera Mohd Isa, 23, a business diploma holder who joined the prison service to learn why people commit crimes and to teach them alternatives.

Many inmates also told the officers that a lack of control was their downfall.

Deputy Superintendent of Prisons 1 (DSP 1) Ottilia Hoo, 35, said: “So in a moment of folly, they took drugs, they went with their friends to do some shoplifting, things like that.”

Sometimes the drug-taking happened because of body image issues. Whatever the reason, some 75 per cent of the women inmates are drug offenders – not that their officers view them through the prism of their crime.

“They can be murderers or drug addicts, it doesn’t matter,” said RO 2 Nurul Hazirah. “Our job is to just render help when needed.”

WATCH: An unprecedented look at life behind bars (8:39)

And to help, these officers must take a professional approach. DSP 1 Hoo, an 11-year veteran, said: “I think it’s very easy to judge when you read the papers and you read about crimes that in your opinion are horrific.

“But at the same time, it’s knowing that when we put on the uniform every day, we have a duty to discharge, and it has to be done impartially, regardless of how we’re feeling.”

She has also seen enough to know there are misconceptions about prison and its occupants. “People think we’re dealing with hardened criminals because of what they see in popular fiction,” she said.

“But at the end of the day, you realise that an inmate is still a person. This person could have been your neighbour or someone you sat next to on the bus.”

The officers themselves come from varied backgrounds – from those with a degree in history and Southeast Asian studies, to those who had worked in other Home Team agencies and wanted to do more than catch the bad guys.

And just as the inmates do not easily fit the stereotypes of them, the officers too are not quite what some expect.

For example, when DSP 1 Hoo was just a job applicant who “thought the chance to interact with people and hear their stories sounded like a meaningful career”, someone questioned her suitability for the role of prison officer.

“He looked at me and said I reminded him of an office lady,” said the diminutive woman. “I think it’s the way I look.”

WHAT INMATES GO THROUGH

While the officers believe that prison is about second chances, the inmates must adjust to the rigours of incarceration before they can be rehabilitated.

In the first stage of their jail term, known as the deterrence phase – which varies in duration depending on each inmate’s sentence and needs – they are confined to their cells for 23 hours a day. This means minimal rehab programmes.

They are allowed one book at a time, and no visits are permitted, except from lawyers, embassy officials or counsellors. The experience allows them to “reflect on their past actions”, according to the Singapore Prison Service (SPS).

Their cells are spartan. Spotted in one were four transparent boxes of the occupants’ belongings, lined neatly against a wall. An arm’s length away, white flannels hung from four of the five hooks on the wall.

All inmates are issued a standard set of toiletries, a wrist tag they must wear wherever they go, and for their bed, they have a straw mat. A low wall separates the sleeping area from the toilet.

There are no mirrors to be found, only a polished stainless steel plate hung in a sports hall, their Recreation Yard. It is the only way inmates can catch their reflection, and queues are common in the one hour of free time they are allowed outside their cells each day.

It gets better for inmates when they move on to the “treatment phase” of their sentence. They can have up to six books – three from their family and three from the library – in their cell.

Unlimited letters from their family are allowed, while they get to send two letters a month. Importantly, they can receive two visits a month, either a combination of a 20-minute face-to-face meeting and a 30-minute teleconference, or two 30-minute teleconferences.

In the day room, the area right outside their cells, there is a television and newspapers in Singapore’s four official languages.

With no internet access, these together with the family visits are the inmates’ touchpoints for the outside world, although certain articles like crime reports are screened out of the papers.

CNA Insider’s visit was a rare sight for the inmates. But it also necessitated DSP 1 Hoo’s reassurance to them that neither their faces nor their identity would be revealed.

FOCUSING ON REHABILITATIVE WORK

As the Officer in Charge of the institution’s Housing Unit 1, she is responsible for its overall management. Yet, despite the weight of the daily operations, she went about with a smile, even bantering with the inmates about prison food.

The use of technology has freed up officers like her for their higher-order work of rehabilitative engagement.

READ: Changi Prison raises tech bar with automated checks, surveillance system that detects fights

In the Recreation Yard stood an example of the automation of routines. At a blue kiosk, two inmates were peering at the screen to check the status of their requests, such as for dental treatment and religious reading material.

Called the Inmate Self-Service Kiosk, it allows inmates to make administrative requests, obtain inmate-related information and even redeem privileges like the purchase of snacks, stamps and greeting cards.

But it is not just technology that is transforming the nature of the officers’ work. In recent months, pilot workshops have been run for them so that they can work more closely with the correctional rehabilitation specialists.

This helps the officers to relate to the inmates better. “The rehabilitative effort is a concerted effort of everybody,” said DSP 1 Hoo.

“But dealing with the issues from day to day is largely (done) by officers. We engage more, we see them more.”

She leads a team of Housing Unit officers and personal supervisors, and the latter oversee the welfare of inmates and their daily activities.

There are about 20 inmates under each personal supervisor, and through their interactions in their respective Housing Units, the officers come to know the profiles of their inmates.

Now that the officers are being taught by the correctional rehabilitation specialists, however, they are better able to reinforce the psychological skills training the inmates receive and to encourage them.

Read: At Changi Prison's Institution A4, women get help to deal with emotions

Ms Charlotte Stephen, SPS senior assistant director of Correctional Rehabilitation Services (Women), explained: “So when (an inmate) gets angry, the officer would remind her, ‘Do you know what you’ve learnt? Instead of shouting, practise your deep breathing, capture your thoughts … and then do it in a way that’s more acceptable.’”

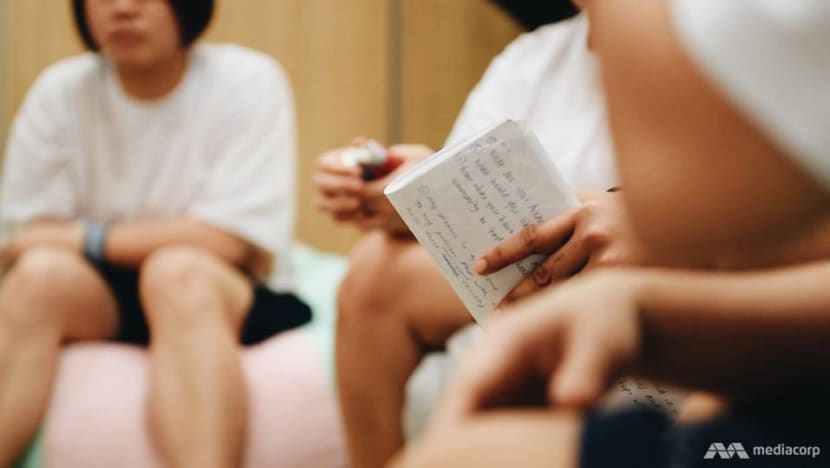

Correctional rehabilitation specialists like her do group interventions, each comprising about 10 inmates in the treatment phase. The psychological-based programme typically runs for six to nine months, with two-hour sessions held thrice a week.

Such rehabilitation remains a work in progress, as part of efforts to reduce the female reoffender rate of nearly 25 per cent within two years of release.

Inside the prison, however, Ms Stephen can see the gains being made with the inmates, who were responsive and relaxed during one such session that CNA Insider observed.

As one of them shared, “I’m quite a quick-tempered person. But as time went by during my incarceration here, I managed to mellow down and change a lot of my thoughts and behaviours, to overcome problems I’ll face in future.”

LOOKING FOR HAPPINESS BEHIND BARS

Apart from the programmes that aim to address stress, drug addiction, anger management and violence, there are family programmes tailored to meet the inmates’ needs as mothers and daughters.

There is also vocational training. The institution includes an art room and a bakery as well as a hair salon opening this year. The certified courses already available include hairdressing, baking and Microsoft Office, besides the academic ones.

Only during such times, when the inmates have rehabilitation activities, do they get to have their meals in the dining hall instead of their cells, if that is more convenient.

There is also a work programme – a tailoring workshop for inmates to mend linens for hospitals – which they can qualify for if they meet the eligibility requirements. These include good conduct and personal interest.

They can save the allowance they receive and use the balance to buy items from the self-service machines in prison. They are also encouraged to send the money to their families.

“Doing actual work, instead of just programmes that equip them with basic skills, gives them an opportunity to have a sense of contributing back to society,” said DSP 1 Hoo.

The pursuit of happiness behind bars is no easy feat. That is why even the little things count for the inmates – like Ms Stephen’s choice of the “beanbag room” for one group session, which prompted a delighted inmate to go “Whee!”

Or take, for example, the pre-recorded TV programmes they are allowed to watch. They get “quite a wide variety” of shows, including films, but they have their favourites.

“In general, inmates do prefer watching variety shows such as America’s Got Talent. Things that have a feel-good factor help them to feel happier,” said DSP 1 Hoo.

That explained the bright colours of their Housing Unit and the murals of motivational messages around them. “Nobody can go back and start a new beginning, but anyone can start today and make a new ending,” read one.

For one inmate CNA Insider spoke with, satisfaction comes from her role as a Housing Unit attendant who DSP 1 Hoo said “helps inmates to go from point to point”, like when they have programmes in rooms on another floor.

The foreigner, who has been incarcerated for about two years now, used to speak very poor English, but the officers encouraged her to learn the language slowly.

The other inmates did not listen to her initially, but now they do. When DSP 1 Hoo asked how she felt about that change, she replied: “Very happy lah. Sometimes I’m scared the officers (would) scold us, but now okay.”

WHAT THEY GET OUT OF THE JOB

When people think of prison, fear might be a word that comes to mind – that inmates are afraid of the guards, acknowledged Sergeant 2 (SGT 2) Nazurah Mohamad Nassir, who started service this year.

“But I think we’re approachable. We listen to them a lot,” said the 22-year-old, the youngest of the officers.

The officers’ hope is that the inmates do not fall into hopelessness.

“No matter how many times (they’re incarcerated) – it can be the first or the fourth – at some (point), they’d realise that there’s someone who wants to help them,” said SGT 3 Alysa Naqeera.

The journey to becoming an officer is not easy, however. The training at the Home Team Academy is the same for both genders, entailing the physical aspect, tactical skills as well as classroom lessons on legislation and prison rules.

“At the end of every day, you just lie flat on your bed and you’re like, ‘Why did I do this?’ But it was what I expected,” recalled DSP 1 Hoo.

Her parents are supportive, though her mother initially had some concerns about her safety and “continues to worry till this day, as mothers do”.

“But she knows I’m doing well. I think they see that I’m happy, despite being tired,” said their daughter. “I guess the fulfilment shows on my face when I get home.”

The officers have eight- to 12-hour working days. But it is also the “emotional journey” of steering the inmates and hearing their stories – of striving to live up to the tagline Captains of Lives – that can be draining.

“Sometimes, as a woman, you feel for them. You can get angry on their behalf. At the same time, you have to bring them back and tell them to make the best of their time here,” said DSP 1 Hoo.

But it takes just a thank you for the officers’ help to make the job rewarding, “simple and cliched as it sounds”, said SGT 3 Alysa Naqeera.

“Just seeing that little happiness from them when we get to answer their questions makes me feel like, at least I did something good today.”

Her boss added: “And when they see you’re willing to help them genuinely, they warm up to you. They respect you.”