commentary Commentary

Commentary: Why the use of women and children raises the stakes in the fight against terrorism

The Surabaya bombings last week involved women and children. The mobilisation of family units is a worrying sign for the fight against terrorism, say two terrorism experts.

Relatives and friends of Martha Djumani attend her funeral in Surabaya AFP/JUNI KRISWANTO

SINGAPORE: In Southeast Asia, families including women and children departed for Syria to join the terrorist group the Islamic State (IS) after its declaration of a caliphate in 2014.

IS called the children “cubs of the caliphate” and looked upon women as vanguards of a future generation of fighters. Videos of ideological indoctrination and military training of Southeast Asian children surfaced over 2015 and 2016.

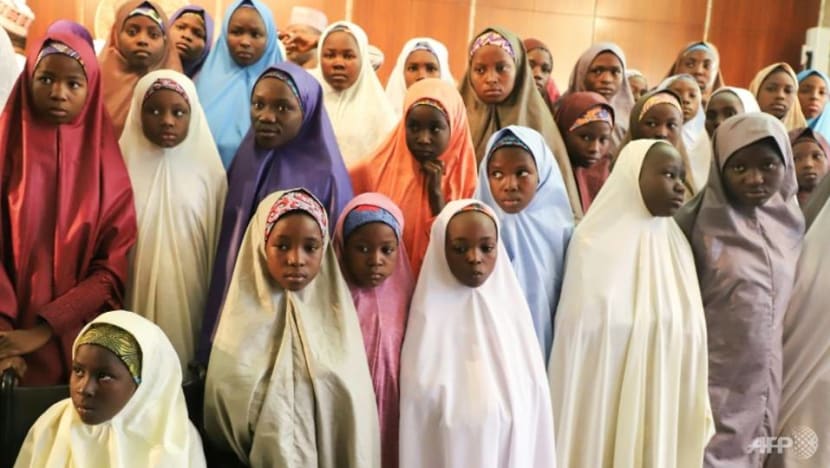

The use of women and children as actors of terrorism is not new. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, Boko Haram and even the Lord’s Resistance Army used women and children to conduct attacks and suicide bombings.

At least two Indonesian children who had fought alongside IS were killed in Syria.

Yet over the last week, the use of children and the family as a unit in the Surabaya bombings has reinvigorated debates on morality and the evolution of terrorist groups in the region.

A recent publication by counter-extremism think tank Quilliam titled Tackling Terror: A Response to Takfiri Terrorist Theology explored the notion of legitimate targets and collateral damage.

The report noted that “women have tended to be classified within a single category ‘women and children,’ and were seen as ‘vulnerable’.”

Yet the recent spate of attacks reaffirms the need to reassess whether this is really so.

The age-old debate of how much agency women and children involved in terrorist attacks, like the recent spate of bombings in Surabaya, have to act independently and have the power of choice versus how much structure was imposed on the family unit by misinterpreted radical ideology or the patriarchal role of men as the heads of households and key actors in acts of terrorism warrants a closer look.

It is often a confluence of factors, so the challenge is moving away from the view that they are vulnerable and left with no choice.

WEAPONISING THE FAMILY UNIT

The involvement of adult family members in joint terrorist attacks or suicide operations is not new. Terrorist groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) have long used familial networks and marriage to recruit, radicalise, and cement their networks as well as to conduct operations in the region.

In this context, the use of children to conduct operations is seen as an enhancement of a strategy to use family units to augment the effectiveness of terrorist operations.

Children have been an integral part of the strategy of Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) and other Indonesian groups aligned with IS. JAD has been uniting various pro-IS elements in Indonesia.

This strategy is seen in the steady, calculated indoctrination of women and children over the years that has in turn led to the latest manifestation – the family unit as a weapon of terrorism.

This makes it harder for detection by authorities given the already diffused network structure now exacerbated by familial ties that inadvertently reduces defection within the ranks.

BOARDING SCHOOLS

JAD has institutionalised the indoctrination of children through its string of pesantren (boarding schools), capitalising on its members’ hesitance in sending their children to study in government schools and mainstream Islamic schools.

Consider JAD’s belief of takfir – a concept where a Muslim accuses another Muslim of apostasy and declares him a non-believer – and its view that the government is a thaghut (an oppressor) that needs to be fought.

Our research has shown that JAD has established boarding schools across the country which ensures children adhere to ascribed standards, leveraging donations from the Indonesian pro-IS community to fund the schools’ running.

They are known to have a number of such schools spread out across Indonesia, including in Sumatra (South Sumatra and Lampung), West Java, Poso in Central Sulawesi, Central Java, and East Java.

Children of incarcerated JAD members who study there pay reduced or no tuition fees.

These schools are usually not registered with the Ministry of Religious Affairs, rendering oversight a key challenge for Indonesian authorities.

Four such pesantren connected with JAD come to mind. Apart from their educational and indoctrination purposes, they have also become meeting places for like-minded extremists within JAD.

The Ibnu Mas’ud pesantren in Bogor, West Java, counts Abu Musa alias Hari Budiman the former leader of JAD among its founders. He is presently believed to be in Syria.

It was reported that at least 18 persons linked with the Ibnu Masud pesantren were arrested for alleged involvement in planning and attacks in Indonesia. Another 12 – which includes eight teachers and four students in the school – had reportedly departed for Syria to join IS.

JAD West Java administrator Fauzan al-Anshori ran Pesantren Anshorullah based in Ciamis, West Java. The pesantren hosted the pledged allegiance of JAD members to IS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, and has served as a meeting point for the JAD cell in West Java.

Some of these pesantren also act as training grounds for young extremists. Children in a JAD pesantren in Muara Enim, South Sumatra for instance, had co-curricular activities that included archery and the use of air guns.

INDOCTRINATION THROUGH HOME SCHOOLING

Radicalisation can also happen outside of these pesantren. The parents involved in the Surabaya Police District Headquarter bombings did not send their children to mainstream schools.

Claiming to homeschool their children, parents made them routinely watch terrorist videos. Research has shown the presence of an e-pamphlet on IS ideology for children in the Indonesian language readily available online that may help supplement lessons.

In the greater Jakarta area, there are dedicated study sessions conducted for women, who make up wives of JAD members, and children. The study sessions complement the more rampant practice of online study communities among female supporters of IS.

CHOSEN WITHOUT CHOICE

The weaponisation of the family unit has raised questions of morality in the use of children in extremism and terrorism but it has not stopped groups like the JAD from doing so.

IS called the children “cubs of the caliphate” but beyond the language of bravado, is a cruel reality tarnishing the sanctity of human dignity enshrined in the Quran where it states that Muslims should honour their children.

Underneath this is a vicious cycle of radicalisation that strengthens the hand of extremist groups.

There is an argument to be made that the very family structures these children are born into have created echo chambers that not only impacts their ability to exercise agency.

They have also led to women in these families embracing a combative role in terrorist attacks – not just for their husbands and for themselves but also for their children.

While the involvement of family units is not a new strategy if we look at other terrorist groups, what this new development means is that Indonesian terrorist groups have raised the ante.

Given its territorial losses in Iraq and Syria, and the inability to gain a foothold in Marawi, IS will continue in its attempts to steadily repositioned itself. These manoeuvres attempt to surprise and project sophistication through their efforts to adapt to an evolving terrorism threat landscape.

Dr Jolene Jerard is deputy head and research fellowat the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies' International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research at the Nanyang Technological University. V Arianti is an associate research fellow at the same centre.