‘Where were you when I needed you?’: The struggles of mothers in prison, longing to see their children

Special occasions like Mother's Day can be especially difficult for women behind bars. Two female inmates spoke to CNA about the challenges of being away from their only child.

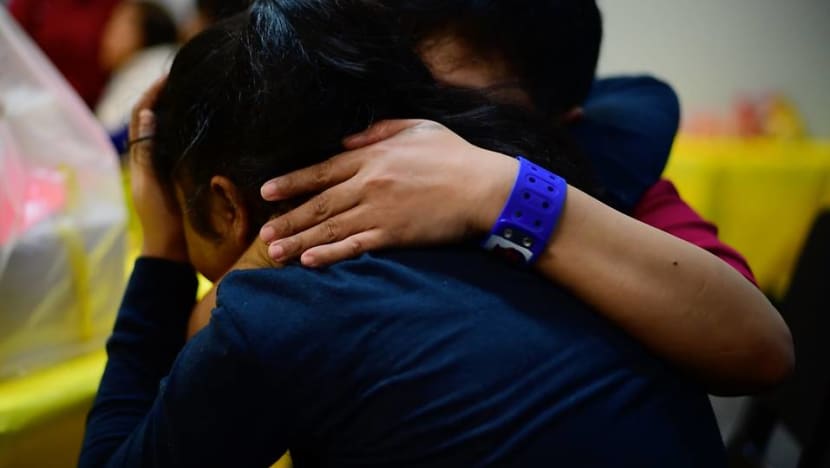

A family reunited, in a photo taken during open family visits conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo: Singapore Prison Service)

SINGAPORE: When Jane’s* daughter was younger, she thought her mother worked at Changi Airport.

In fact, Jane is an inmate at Institution A4 in Changi Prison Complex, which houses female prisoners. She was sentenced to jail for drug-related offences about two years ago, and this is not her first time behind bars.

“When my daughter was three or four years old, I was serving my previous sentence. I would tell her: ‘Mummy’s overseas working. When you come to tele-visit me, this is the airport.' The prison officers are airport security, those people who scan the bags,” the 27-year-old told CNA over Zoom from Changi Prison.

READ: Recidivism rate at all-time low; more inmates serving part of jail term in community: Prison Service

But Jane said her daughter, now eight, has wisened up.

On her last few visits to Changi Prison, she started asking: “Where are the airplanes? Where is mummy? Where were you when I needed you?”

During one visit, when Jane told her daughter that she missed her, the child's response was: “Stop lying.”

“She told me that if I loved her so much, I wouldn’t do what I did and I would still be around. I wanted to explain that just because I did those things, doesn’t mean I don’t love her. I’m just facing difficulties with myself, so I took drugs,” said Jane.

“But I couldn’t answer her, so I just sat there dumbfounded and cried.”

MOTHER’S DAY BEHIND BARS

Mother's Day - and other significant occasions - can be especially difficult for inmates such as Jane.

Despite being in prison for the fourth time for drug-related offences, Sarah* said special occasions have hit her hard. She gave birth just before her most recent arrest, and her son is now two years old.

Speaking to CNA over Zoom, she said she sank into depression when she missed her son’s significant milestones, such as his first steps, his first words and his first birthday.

“The saddest part was when I first started this sentence around the circuit breaker. No visits were allowed. I didn’t know how my baby looked like after a few months,” said the 31-year-old.

“In the letters, I told my family that next time I call, make sure the baby’s awake. Once, I got to hear my baby crying, I was so happy that I couldn’t sleep that night.”

Sarah will narrowly miss celebrating Mother’s Day on Sunday (May 9) with her child. She will be released from prison towards the end of May, and she is looking forward to seeing her son once she is out.

“He has been my strength and the motivation for me to keep myself clean without getting into trouble in prison. He’s the first person I’m going to meet,” she said.

READ: Inmate stressed by long sentence, family's disappointment finds comfort in supportive prison officer

As for Jane, this Mother's Day won't be the last that she will spend away from her daughter. She will only be released in 2023.

Jane and her daughter last saw each other in November last year during a prison visit. And although their relationship has become increasingly fraught, certain memories keep Jane going in her darkest periods.

For instance, before she was re-admitted for her current sentence about two years ago, she visited her daughter’s school for a celebration.

“She didn’t know how to react to mummy being around, so she cried, and I ended up crying with her. I was about 25 then, she was six. It was like a child taking care of a child,” she said.

The hardest thing about being apart, Jane added, is realising her daughter might learn to “live without mummy”.

“In the past, she would follow me everywhere I go. Now, she thinks it’s okay, she can live without mummy. I don’t want her to have that thought because I could never, ever live without her. But she’s probably gotten used to me not being around,” she said.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, visits by her daughter have been dwindling, Jane said, attributing this partly to her divorce from her husband, who is also incarcerated.

“Things started changing between me and my in-laws, probably because I filed for divorce in 2018 when I was previously released. So I don’t see my daughter as regularly now, and I don’t get updates (from them) as much anymore,” she explained.

HELP FOR INMATES

For female inmates like Jane and Sarah, the mental and emotional distress of being away from their children can be difficult to bear, in addition to having to worry about other arrangements.

As such, both of them are beneficiaries under the Initiative for Incarcerated Mothers and Affected Children (IIMAC) developed by the Singapore After-Care Association (SACA).

The initiative ensures that “first-level intervention is offered to mothers” with children aged 16 and below, said Ms Noraishikin Ismail, a manager for the volunteer after-care programme at SACA.

“Assessment and referral to appropriate services will go some way in helping to ensure that these innocent young persons don’t suffer any more than they already have, and are protected from any harm that may arise from inadequate care arrangements,” she added.

After seeking an inmate’s approval to contact their family, SACA’s volunteers find out what assistance families need.

In Jane’s case, IIMAC helped by arranging for a community volunteer to tutor her daughter, as her former in-laws could not afford tuition.

Sarah, on the other hand, received financial aid for her son’s diapers and milk powder.

“Mothers who were the primary caregiver to their children prior to their incarceration are generally overwhelmed by the separation from their children. Having this initiative helps them voice any concerns they might have,” said Ms Ismail.

Officers in the prison have also seen the initiative make a difference to incarcerated mothers.

“We’ve worked with SACA to run the IIMAC programme for almost 10 years. It has reassured mothers that despite being in prison, they have (external) support to look out for their families’ welfare,” said Ms Lydia Tan, a rehabilitation officer.

“This gives inmates peace of mind to focus on their rehabilitation and personal development, so they can return to their families as a more involved mother and caregiver.”

PERSONAL MOTIVATION STILL KEY

Beyond relying on programmes like IIMAC, Jane and Sarah understand that being able to give their children a better life when they are released from prison means working on themselves now.

Jane, for example, is studying for the GCE Normal (Academic) Level examinations to keep herself productive.

“When I was arrested again, I realised that my daughter isn’t going to want me anymore if I keep doing this. If I don’t stop my habits, one day I’m going to lose my daughter, like how I’ve lost my freedom,” she added.

“Of course I cannot stop her from having problems, because everyone has problems, but I want to be there to help her overcome these problems instead of running away like what I always do.”

READ: 'Outside, we don't get a chance': What it is like studying for a degree in prison

As a fourth-time offender, Sarah said the struggle of staying out of prison lies in “finding new friends and coping mechanisms”.

“I have a lot of mixed feelings (about getting released). I’m having a lot of anxiety. I’m scared. I need a lot of support and people to be there to tell me that I can do it,” she said.

“If I look for drugs again, I will lose my freedom and I will lose this opportunity to spend more time nurturing my child.”

*The names of inmates have been changed to protect their identities.