Real-life CSI: This forensic pathologist in Singapore searches for clues in dead bodies to help solve crimes

CNA Lifestyle visits the mortuary to find out what forensic pathologists like Dr Lee Chin Thye do – and is it anything like true crime TV shows.

Forensic pathologists don't work alone during autopsies, said Dr Lee Chin Thye (left), seen here with a forensic technical officer (right). (Photos: Joyee Koo)

There’s no doubt that the true crime genre is enjoying a resurgence of late. Chances are, you've got hit docuseries such as Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, The Serpent, and The Sons Of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness all lined up for a weekend of macabre streaming pleasure on your TV or mobile devices.

Or you might already be familiar with early 2000s crime drama offerings, including CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (and its spinoffs, of course), Criminal Minds, and Bones.

Naturally, you would have formed certain impressions of the mortuary and how post-mortems are carried out. A dark, windowless room in the basement illuminated only by operating theatre lights and walls lined with metal doors. Someone in scrubs leans over the body in question and pushes aside some organs to reveal the cause of death to the enquiring detective. Cue dramatic music.

Except that in real life, things aren’t quite the same – well, at least in Singapore. For one, the autopsy room at Blk 9, Outram Road is more wet market than dungeon to this writer's mind: Metal sinks, weighing scales, white cutting boards and plastic bag-lined bins. It smells sterilised but without the heavy after-odour of disinfectants.

Yes, there are no windows but the room is spacious, brightly lit and has a long, elevated platform running down the middle. On each side of the platform, cleaned and restocked workstations stand at the ready to receive the next case.

And what of the ubiquitous wall of metal doors that open to drawers containing corpses? Think cold rooms instead – walk-in refrigerators that don’t look very different from spacious cargo lifts. And like those metal-plated elevators, there are two sets of doors: One for the police to load the bagged and tagged bodies for secured storage after-hours and the other for the staff to access in the morning. That’s right, they don’t work through the night like what Hollywood says.

In the cold rooms, the bodies are placed on metal gurneys, then lined up side by side in temperatures not higher than 4 degrees Celsius. Special cases though, such as suspected infections and severely decomposed bodies, are stored separately in industrial-sized refrigerators with drawers.

5,000 CASES A YEAR

The bodies that arrive at the mortuary are usually the result of unnatural, violent or unexplained deaths. “Examining a body helps us to answer the questions of who the deceased was, how the deceased died, and when and where the deceased died. These are the purposes of the coroner’s investigations and inquiry,” said Dr Lee Chin Thye, 45, one of the eight forensic pathologists with the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), the only organisation here that hires these professionals.

Interestingly, not every corpse that comes through those metal doors undergoes a post-mortem. After the requisite documentation, such as general photography of the body and measuring its weight and height, a CT scan is first performed before any dissection, if at all.

“Based on the scan, and information from the police and medical records, we can better advise the coroner as to whether or not an autopsy is required,” said Dr Lee.

But surely there aren’t that many unnatural deaths in Singapore to examine, are there? Make that 5,000 cases a year on average. “It equates to about 13, 14 cases a day,” said Dr Lee, who has been working with HSA for 16 years. “The maximum we’ve had in a day was 28. The lowest could be one or two cases. The highest number of autopsies I’ve done in a day is six.”

And no, there isn’t an organ that takes a longer time to remove than the others, according to him. “The difficult cases to dissect would be those where the normal anatomy may have been altered. For instance, a complex surgery had been done.

"On average, a routine autopsy would take somewhere between one and two hours. But in homicidal cases or cases that are more complex, they could take upwards of six hours or more,” said the doctor.

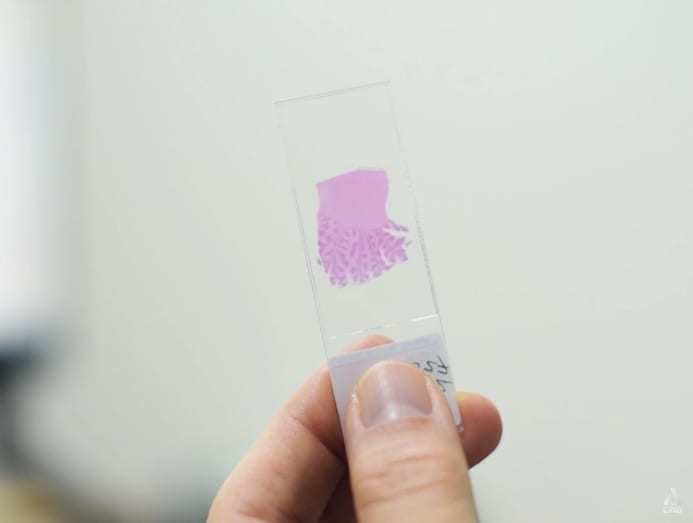

PINK SPECIMEN SLIDES AND PAEDIATRIC DEATHS

When CNA Lifestyle met the forensic pathologist in his office in the HSA building, a few blocks from the mortuary, he was poring over some specimen slides – pieces of glass with a bright pink stain in the middle. The slides allow the forensic pathologist to see details that are not obvious, explained Dr Lee.

“For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, pneumonia sometimes may not be clear to the naked eye when we examine the lung. So we have to look into the tissue to see the inflammation and infection.”

To do that, tissue samples are removed during autopsy, treated in formalin, encased in paraffin and sliced. “Just like it is much easier to cut frozen than fresh fish, it is much easier to cut the paraffin block to get an even slice,” he said, noting that this is done at a lab. The process results in specimen slices that are 3 to 5 microns thick, or the thickness of a single cell – certainly thinner than the bonito flakes sprinkled on takoyaki.

As for the peculiar colour, that comes from a pink dye that is used to stain the specimens (most cells are colourless and transparent) and make them visible. Finally, the slices are sandwiched between pieces of glass and ready for examination under the microscope.

Dr Lee held up a slide to the light. It contained a specimen shaped like a human heart but smaller than a walnut. Isn’t the average human heart the size of a fist? “It belonged to a baby,” he said. “I have three children (ages seven to 14), so I still have difficulty dealing with children who pass away for whatever reason.

“The public may think of forensic pathologists as heartless or have no feelings. Perhaps they think that we can somehow detach ourselves emotionally while performing an autopsy. But I personally can recount the many times I had to compose myself when I encountered paediatric deaths.”

WHEN THERE ISN’T A BODY

Fans of true crime shows would know that dead men can tell tales, and it’s not that far-fetched in reality either, such as the case that involved a dead seaman. “At first, the cause of death was thought to be due to heart disease. However, the toxicology report showed lethal levels of methanol,” said Dr Lee.

The characteristics of a wound can ascertain the cause of death as well. For instance, multiple stab wounds on the chest could lead to the assumption that a punctured heart or lung might have been the cause of death. But if the deceased was found to have bled out from a cut artery instead, it could mean a difference between manslaughter and murder.

But what if there wasn’t a body to examine at all? If you’re familiar with the Gardens by the Bay murder case, you might recall that the victim’s body had been reduced to ashes. “One of the things that the police was very interested in was whether or not there were any human remains I could identify,” said Dr Lee. “There was a lot of burned debris. I stayed for almost two hours to search and comb the surrounding area.”

He recounted that the CT scanner was used to identify any bone or teeth in the debris but there weren’t any such identifiable remains.

The breakthrough was when one of the staff identified an object just over 1cm wide as part of a bra. “It subsequently turned out to be a bra hook,” he said. “And the forensic science lab matched that to some of the clothing that was found in the victim’s house. That gave us hope that there could be human remains and it placed somebody who was female at the scene.”

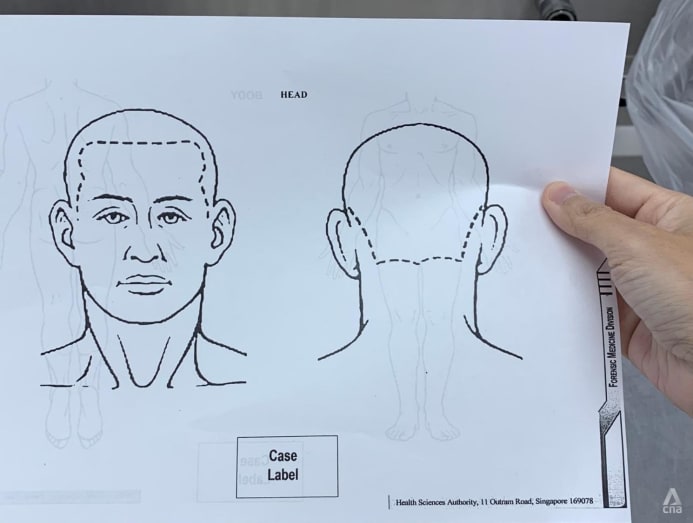

At some point in time, the team also found some strands of hair. “I mounted them in glass slides and looked at them under the microscope. There are different characteristics between human and animal hair – and it turned out to be human hair,” he said. “I quickly submitted the evidence to the police and DNA lab for profiling. From the bra hook and hair strands, the police was able to identify the deceased.”

WHAT TV DRAMAS AND MOVIES GOT WRONG

What does happen in real life (and on TV) is the removal of the organs for weighing and measuring. An enlarged heart or thickened walls of the heart could point to heart disease, for example. Blood, bodily fluids and swabs taken from intimate areas are also collected and sent for analysis.

However, forensic pathologists don’t work alone as is often depicted on the screen. “We have at least three forensic pathologists on duty at the mortuary,” said Dr Lee. “On top of that, we also train doctors to be either forensic pathologists or histopathologists. On average, we have at least five or six trainees with us at any one time.

“I am also joined by two or three forensic technical officers, who will help with the autopsy and release the deceased back to their next-of-kin. These officers take charge of other areas such as biosafety and post-mortem imaging as well.”

FORENSIC PATHOLOGISTS ON STAND-BY

Like ambulance personnel and other emergency services, forensic pathologists who are rostered, are also put on standby during major events in Singapore, such as National Day. They have to be at the mortuary at short notice should any incident occur.

Forensic pathologists are also on call for attending crime or death scenes. “When I’m rostered, I always have a bag packed with a change of clothes, notebook and pen, ready to go,” said Dr Lee. In fact, he was having dinner with his family when he was called to attend the Gardens by the Bay case.

The one depiction that irked Dr Lee is how quickly TV characters often arrive at the results. “Crime shows appear to always have all the answers and in the shortest amount of time, like within half an hour, including advertisement breaks,” he said in jest. “In reality, it takes about a day to conclude the autopsy and write up the report.”

Another faux pas, according to him, is that forensic pathologists are often shown analysing the collected evidence. “You may have seen on TV that the character who collects the blood or DNA from the body is the same one who puts it into a machine for the test results. I don’t perform toxicology analysis. Instead, the samples are sent to a specialised lab and the results take about a day.”

The public may think of forensic pathologists as heartless or have no feelings. Perhaps they think that we can somehow detach ourselves emotionally while performing an autopsy.

Also, forensic pathologists don’t stay holed up in the autopsy room all day. “The day is very varied,” said Dr Lee, who starts work at 8am. “Usually, I’ll review the cases from the previous day. After consulting with the coroner, we would proceed with the autopsy or not, depending on the coroner’s decision.”

Post-mortems typically end past noon but his day is far from being over. There are reports to write, and clarifications on previous cases to look into. “I’ll go for interviews with lawyers as well as attend court. On and off, I will also attend to death scenes if I’m called upon. Depending on what I have to do, 5pm or 6pm is usually the time I end.”

So, no late nights and spooky encounters then? “I can’t say I have any personally,” he said with a chuckle. “And I haven’t heard from my staff either. But I believe the mortuary is the last place for spirits to haunt; more likely for them to be found at the scene of death, don’t you think?”

Now, surely, there must be a docuseries or movie that best depicts his profession? “I don’t really want to pick one,” said Dr Lee. “But I will tell you the one I like the most: CSI Miami. It’s not just Horatio Caine who looks very cool with his sunglasses on that show but everybody else as well. It’s like watching a super-hero movie; you want to see a cool-looking hero.”

GETTING INTO THE PROFESSION

Although forensic pathologists deal with the dead, they are medically trained doctors. “One must complete housemanship, and the seamless post-graduate training programme in forensic pathology while passing the requisite professional exams set by the Royal College of Pathologists in either the United Kingdom or Australia,” he said.

Dr Lee himself was on the path to becoming a surgeon when he had a change of heart. “When I was a medical student and even as a young doctor, I was very interested in surgery. But after three, four years into my training, I realised surgery was something that wasn’t suitable for me.”

At that time, he did an elective in forensic pathology as he’d wanted to “see more anatomy and perform dissections”. “It was then that the seed of interest was planted,” he said. “There are similarities between surgery and forensic pathology. Both areas are very much hands-on and secondly, both involve operating or dissecting to diagnose conditions.”

What else does it take to be a forensic pathologist? “I’m not sure if a strong stomach is what it takes but if I have to name one, it’s to have a strong sense of curiosity. One of my colleagues puts it this way: Be kaypoh.”

As for any strong emotions Dr Lee might have when performing his very first post-mortem, well, there weren’t. “The first time I performed an autopsy was as a medical student and it was done as a demonstration for other students,” he recalled. “I had already been taught how to perform it. It was exciting because I had wanted to do it.”

If I have to name one, it’s to have a strong sense of curiosity. One of my colleagues puts it this way: Be kaypoh.

To date, there was “never ever any feeling of repulsion or anxiety” when he is dissecting a body; neither has there been a case that had adversely affected him. “But there are cases that I approach with a sense of dread. Besides paediatric deaths, the other category would be road traffic accidents,” he said. “I recall early in my training, I would get anxious and imagine the worst whenever it was raining heavily and my wife had not returned as expected.”

FAMILY, FRIENDS AND LIFE

So far, he has not have to perform an autopsy on someone he knows. “My wife and I are both born in Malaysia, so that’s probably why I have not. If it does come up, I would avoid taking on the case because of the conflict of interest. I’d pass it to my colleagues.” As for his family’s reactions (including his parents and in-laws) to his unique job, Dr Lee shared that they have been very supportive.

“My family and friends think of my work as being very righteous and helpful to people and society. Perhaps it’s because I have been feeding them the right information.” In fact, when he was notified to leave for Surabaya to assist in disaster victim identification after the AirAsia air crash, “my two older kids ran around the house, screaming ‘daddy is going to go help people in Indonesia’,” he said.

However, he acknowledges that not everyone can accept the morbid nature of forensic pathology. “One of the things we tell potential trainees and hires is, you have to clear this with your family first. You need to ask them whether it’s okay or not. It was one of the things I’d also done. I didn’t have children back then but I had to ask my in-laws and my parents just in case someone has something against what I wanted to do.”

How has encountering death daily at work shaped his take on life? “I feel that life is a very quick thing. Having interacted with the deceased’s next of kin, I’ve come to know that it’s important to cherish the people you have while they’re alive. I’ve seen a lot of regrets, a lot of people who wished they had more time.

“I don’t know if that can completely answer the question but I hope it gives an idea how I feel at this moment about life based on what I’ve seen in my job. It has evolved and I’m not sure how it’s going to go,” he said.

You’ve seen them in shows like CSI and Criminal Minds – but have you ever wondered what a forensic pathologist does in real life? We talked to Dr Lee Chin Thye, who was involved in investigating the Gardens by the Bay murder case in 2016.