From phones to face masks: Why some everyday products aren’t designed for women

From cars and gadgets to life-saving medicine, products and services default to male specs, leaving women cold. CNA Women digs into how it’s still a man’s world – and how it's time to say goodbye to "pink it and shrink it" stereotypes when it comes to products for women.

Have you ever wondered why you need to hold your smartphone with both hands? It’s because mobile phones are made with men’s larger hands in mind. (Photo: iStock/oatawa)

Soul legend James Brown sure wasn’t kidding when he crooned that this is a man’s world.

Despite companies pouring more money into product research and development than advertising these days – a Harvard Business Review report puts the ratio at 10 to one – it still feels as though many goods and inventions are simply not made with women in mind.

Take smartphones for instance. Because women’s hands are typically smaller than men’s by about 2.5cm or so, phones over 12.5cm are difficult, if not impossible, to use with one hand without fumbling or dropping. Yet phones are getting ever bigger, with the largest current models nearly 17.5cm in size.

This male-leaning tendency was noted in a 2010 expert paper on the gender dimensions of product design, prepared by a group of Danish researchers for the United Nations.

The paper concluded that there is a male gender bias in many tech products, and that differences in male and female preferences need to be considered in order to create products that cater for women, too.

Many of the most popular health trackers, like Fitbit and Nike, did not have a period tracking function in their initial models. Neither did Apple’s in-phone Health app when it was first released in 2014, although it covered everything else from calorie count and respiratory rate to sodium intake.

In her 2016 study, data scientist and sociolinguist Dr Rachael Tatman found there was a 70 per cent chance that Google’s speech recognition software would register male speech more accurately than female.

Not that such disparity is limited to the field of technology.

Think about power tools which are unwieldy and heavy for women to use, work chairs that are not ergonomic, food jars and can or bottle openers that aren’t friendly to female hand sizes and strength, and face masks that don’t fit well on women’s faces.

RELATED

More alarming still are the health and safety consequences.

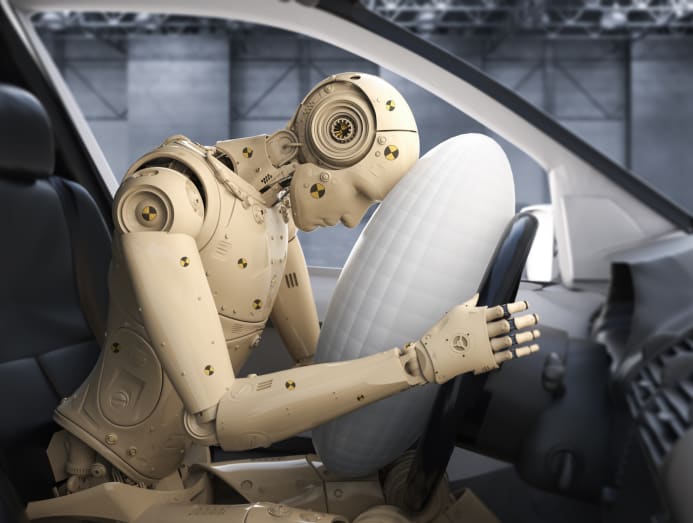

Since the 1970s, car safety tests have been using crash dummies based on the 50th percentile male body, which is considerably taller and heavier than the average woman. But despite various research showing that this puts women at far higher risk of injury than men, the first female crash dummy wasn’t developed until 2012 and is still not mandatory in tests now.

It’s a similar story in medicine. In Singapore, CPR dummies with a female physique only officially came into use this year.

Heart attack symptoms are based on male experiences, resulting in doctors possibly missing the condition in women because they display “atypical” signs.

And historically, medical research and drug trials have either excluded women because their shifting hormones complicate results, or don’t separate the findings by gender. Instead, it is simply assumed that what works for men works for women, too.

MINDING THE GENDER GAP

It’s been said that women are the most powerful consumers in the world today and the stats more than back this up.

In the United States, women influence 85 per cent of buying decisions and drive 70 to 80 per cent of consumer spending. A Global Times report puts the female consumer market in China in excess of 10 trillion yuan (S$2.08 trillion) in 2020, with women contributing 75 per cent of total household consumption and buying half of male-targeted products.

And on a global level, market research firm Frost & Sullivan found that the female economy is set to outpace some of the biggest nations’ economies in the next five years.

So then, why is the male gender still the default standard for product design while women’s needs are not captured?

For an explanation to that, we probably have to look at where the gender imbalance starts – the universities, design companies and engineering firms.

According to statistics from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), fewer than 20 per cent of students enrolled in engineering and architecture in Singapore are females.

The picture looks better when you zoom out, with the Ministry of Education reporting that women accounted for 41 per cent of university students pursuing degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in 2019. Even so, only 30 per cent of local researchers and engineers are women.

Over in the UK, a 2018 study by the Design Council found that 78 per cent of its design workforce is male; this rises to a whopping 95 per cent in the sub-sector of product and industrial design.

Trechelle Lyn Ras, a learning designer at digital creative business school Hyper Island, who also teaches design and innovation modules, called this lopsidedness “the design debt that’s been generated by years of male-dominated industries”.

She added that achieving equal representation and inclusive design would require many things to fall into place. “Education, the availability of talent, the design principles of companies, business opportunities, the technology that makes production possible, to name just a few. It’s a whole system at play,” she said.

For now, many companies simply fall back on the “pink it and shrink it” game plan, where products are made smaller, cuter and in a range of pretty hues without understanding what women actually want them to do. What good is a toy-sized drill or hairdryer or laptop with swirly floral patterns if it’s underpowered and can’t get the job done?

It goes to the heart of the problem: A failure to grasp that gender – both the designer’s and the user’s – affects design.

“Often, designers forget they are designing for others and that they carry biases and views which can colour the products they create. This takes a lot of awareness and courage to admit and many designers are just not yet equipped with this level of introspection.

“They don’t realise the responsibility they have to the creations they put out and the potential impact on users,” said Ras.

LEVELLING THE DESIGN FIELD

While all this may seem rather depressing, there are promising signs that things are, slowly but surely, looking up.

Associate Professor Yang Hui Ying, who specialises in engineering product development at SUTD, said that although there are certain gaps between males and females in terms of income, education, and employment, the situation on the whole has been improving for women over the past decades, especially in developed countries.

“Women now have the same capabilities and opportunities to perform and excel in jobs and activities that used to be done by men. Therefore, to rethink many of the ordinary items that we use in our daily life and design products with less gender bias is a very important task with huge potential market,” she said.

She cited gender-neutral bicycles, which come in a wider fit range, with smaller incremental changes between sizes, enabling them to suit all riders. Household products like vacuum cleaners that used to be considered housewife items have also evolved, taking a more genderless form, such as cleaning robots.

Ras attributes the recognition of design’s gender bias to the rise of feminist movements. “In the last few years, movements like Me Too, Women’s March and manels (all-male panels) have been pivotal in renewing interest in women’s rights and shedding light on the plight of women living in a world dominated by men,” she said.

With this growing awareness also comes an understanding that the problem goes back to the beginning of the design process, where there is a lack of female representation in both the classroom and boardroom.

“I think it would be better if more female designers can join the engineering and technological industries so the opinions of female designers can be heard, as there are still some disconnects between female consumer demands and the number of female designers at the table,” said Associate Professor Yang.

Echoing this view, Ras sees education as a powerful tool for bringing about change, not only by increasing sensitivity towards the issue but also by shaping the lenses that people take with them into the roles they play.

“Inclusive design starts with inclusive teams. That is why at Hyper Island, we instil the importance of human-centred, collaborative teams. Sharing a wide range of disparate views is critical to creating a complete picture of a problem or need, and developing solutions that meet the needs of the many versus the few,” she said.

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg.