As Cambodia mulls high costs, is hosting SEA Games worth the money?

Cambodia is in a race to get facilities ready for the 2023 SEA Games. (Photo: Jack Board)

PHNOM PENH: The reported news that Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen had cancelled the country’s hosting of the 2023 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games last week had sporting officials throughout the region flummoxed.

“I had so many phone calls. It was chaos,” said Vath Chamreoun, the secretary general of Cambodia’s National Olympic Committee (NOC).

A “translation error” by a local media outlet had caused the confusion, after Hun Sen had lamented the high costs of hosting the region’s premier sporting event, during a speech at a ceremony for a new bridge.

“The government is trying to save money,” the prime minister said, as quoted by the Khmer Times.

“If we want to host the SEA Games, we have to spend millions to make venues for the sports and for athletes to stay, and we’d rather put that money toward building more bridges and roads.”

Amid the flurry of international enquiries, the NOC was quick to reassure its regional neighbours – and the country itself – that the Games would go on.

But Hun Sen’s public questioning of the financial burden placed onto Cambodia’s developing economy, for the sake of sport, brought the merits of the plan into attention.

Already, Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte had threatened the same thing: Scrap the 2019 edition of the Games to redirect money towards fighting extremists in the country’s south. Hosting rights had already been thrust upon Manila after Brunei reneged on its 2019 commitment and withdrew.

"Resources shall be focused on rehabilitation and rebuilding of Marawi instead of funding the 2019 hosting of the Southeast Asian Games,” Philippine Sports Commission chair Butch Ramirez said in July, before the decision was reversed the next month.

Holding the SEA Games – and the 30 to 40 sports that come with it – requires a major investment in infrastructure and human capital. That has not stopped the region’s poorer nations, Laos and Myanmar, from playing hosts in the past decade.

For Cambodia, the bill will run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

“This is a concern, but when we have proper savings over a period of time, we don’t think that we are taking a big risk,” Chamreoun said.

“This infrastructure will be a great legacy for the next generation, for them to train and educate themselves, both mentally and physically.”

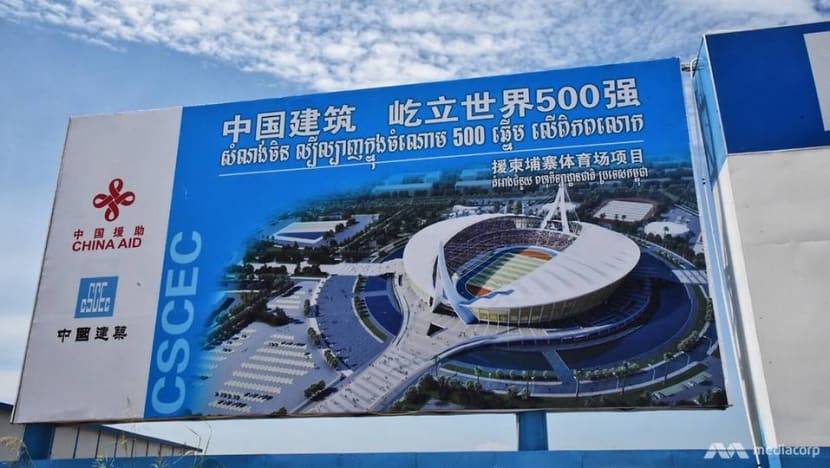

The showcase item for 2023 will be a purpose built 60,000-seat stadium, currently being built as part of the Morodok Techo National Sport Complex, 15km north of Phnom Penh.

The entire project – costing some US$160 million – is being paid for and constructed by China, as a "symbol of friendship".

Similarly, Beijing has stepped in to construct stadiums in Myanmar and Laos, part of a wider investment and soft power strategy in Southeast Asia.

China has plied Cambodia with aid packages and grants and loans worth billions of dollars in recent years. It is Cambodia’s most important trade partner with a burgeoning political friendship that has seen Phnom Penh increasingly sever ties with western partners.

“It is normal for countries who host big sporting events to get assistance from their friend countries," Chamreoun said. "We cannot be narrow-minded."

Even with a pipeline of finances seemingly assured from Beijing, the greater risks for Cambodia come if their audacious new sporting complexes become white elephants after 2023.

“There is already a lot of money – hundreds of millions – going into infrastructure here," said Stephen Higgins, managing partner of Mekong Strategic Partners. "Now if the Games weren’t happening, would that money be diverted to other infrastructure? Maybe, maybe not."

He added: “The big test is, is it creating infrastructure of value to the community in the long term? The issue is when investment goes into facilities that, once the Games are over, never get used again – and that’s just a dead loss to society."

Making proper use of a modern swimming complex and multi-thousand seat stadiums for several other indoor sports could prove unrealistic for Cambodia’s fledgling sporting sector, despite promised budget increases for sporting development in the coming years.

Chamreoun says the NOC and government have solid, commercially minded plans to ensure that does not happen after 2023.

“Our concept of building the infrastructure is a business concept because our stadium has shopping inside, has a hotel inside,” he said, adding that Cambodia would transform other remaining spaces to be commercial centres, movie theatres and exhibition spaces.

But he was also keen to stress on the less tangible benefits of hosting the Games, such as national pride. Cambodia is the only country aside from Timor Leste not to have held the competition since it began in 1959.

“The success of big sport events is success for the whole nation. It means that our nation has a good reputation. It is an event bringing unity and friendship and peace in region and in the world.”

Phnom Penh was meant to have held the Games back in 1963, at the time building its Olympic Stadium, an iconic structure that still benefits the city today.

That edition was cancelled due to unstable domestic politics. Notably, Cambodia will once again have political considerations in mind six decades later: a general election is also scheduled in 2023.

For the nation’s athletes, politics and economics are a distant thought when compared to the potential thrill of competing on home soil.

When Meun Sophea stepped into the ring in Kuala Lumpur earlier this year for his first SEA Games competition, he was nervous. For the celebrated Cambodian kickboxer, this was unfamiliar territory: He was confronted with the nuances of point-style boxing and a hostile crowd.

The 27-year-old did his nation proud though, claiming a silver medal in Muay Thai and helping elevate Cambodia’s style of combat fighting throughout the region.

“It made other countries know about our Khmer martial arts,” he said.

“They did not know what Kun Khmer is, but when we started to fight in the ring, they started to realise that Kun Khmer is also strong.”

Sophea knows he probably will have hung up his gloves by the time Cambodia’s hosting year comes around. Still, he hopes young athletes now are being inspired by the future opportunity.

“I support Cambodia to host the Sea Games in 2023. It makes people know about the value of our culture and civilization and the younger generations will be more interested in sport.”

“If I was available then, I would be very happy to fight in our home town and as a host,” he said. “I want to fight very much.”