commentary Asia

Commentary: Should we be worried about North Korea?

North Korea is unlikely to significantly change its behaviour any time soon; neither will the US likely back off or down, says Bernard Loo, associate professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Kim Jong Un is playing a dangerous war game. Under his leadership, North Korea has sped up its nuclear programme. (Photo: AFP/KIM JAE-HWAN)

SINGAPORE: In recent months, North Korea appears to be playing a game of chicken with the US. Apart from undertaking two missile tests to build up a long-range missile capability, it has also sped up its nuclear programme development.

These moves have not gone unnoticed or unanswered. Earlier last month, US President Donald Trump announced that the US Navy would deploy an “armada” led by aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson to the waters around the Korean peninsula in response. North Korea’s actions have also sparked off a flurry of shuttle diplomacy from China.

Of course, it turned out that the USS Carl Vinson had departed from Singapore and was actually headed towards the Indian Ocean to take part in exercises with the Royal Australian Navy. Eventually, the aircraft carrier deployed to the waters off the Korean peninsula, as Trump had initially claimed.

Keen observers are watching developments off the Korean peninsula with great interest, as people around the world worry about whether conflict is imminent. Some wonder, why do such military moves seem to be making things worse when they are supposed to deter North Korea? More importantly, should we be worried about North Korea’s weapons development and nuclear programme?

A FAILURE IN DETERRENCE

In itself, the deployment of the aircraft carrier battle group to the waters off the Korean peninsula, even if this happened right after Trump’s initial announcement, is nothing remarkable or unprecedented. Countries in the past have deployed military assets in response to provocative moves by another country, and especially those by a putative adversary.

Obviously, there is a range of reasons why countries deploy military assets. The military is after all a tool of foreign policy. We can be forgiven for forgetting that “war is a form of politics by other means”, as the memories of war fade from Asia.

Most of us have an idea of the totality of war, as images of complete destruction and the levelling of cities from World War II dominate our judgment of what conflict entails. But how many of us actually remember that the last outbreak of armed hostilities in Southeast Asia wasn’t actually that long ago – which includes a civil war in Indonesia that led to the breakaway of Timor-Leste in the late 1990s or a border fight between Thailand and Cambodia over the Preah Vihear just five years ago?

In the case of the deployment of the USS Carl Vinson, ostensibly the intent was not to start a full-scale invasion but to shape North Korea’s behaviour: To compel North Korea to cease its missile tests and deter it from conducting a nuclear test that Pyongyang was widely rumoured to be contemplating.

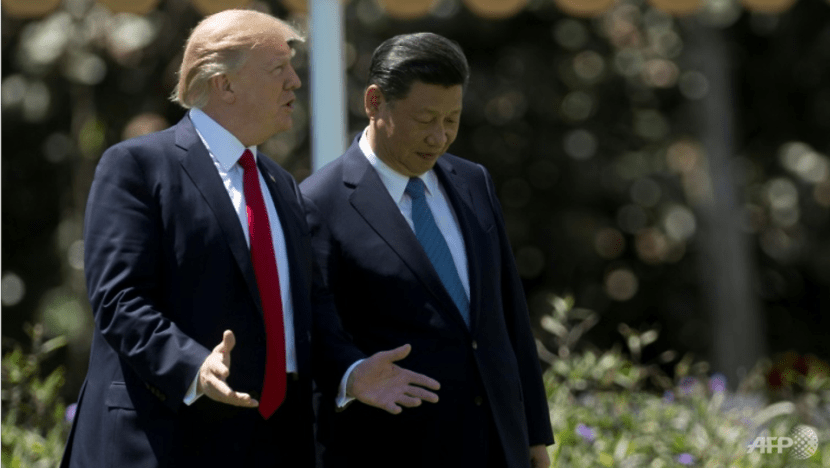

After all, surely as a shrewd businessman, Trump understands that the definition of power is the ability of one party to change the behaviour of another. The logic goes: North Korea has done some very bad things in undertaking a missile test when Trump first met with Xi. So if the US deploys an armada, it will show North Korea that the US means business and they will back off.

Except it is clear that the USS Carl Vinson failed to do precisely the first – North Korea tested an apparently new ballistic missile capable of carrying a large nuclear warhead on May 15. But in a way, the US’ move was able to, to some extent, demonstrate resolve to respond to provocation from North Korea and signal the US’ displeasure to an unfriendly moves at a critical time, when Xi and Trump were meeting for the first time.

That this move was limited in shaping North Korea’s behaviour, however, is worrying.

GLARING GAPS IN NORTH KOREA'S BALLISTIC MISSILE PROGRAMME

The problem is that North Korea’s endgame is not entirely clear; nor is it clear how its ballistic missile programme and nuclear ambitions fit with and contribute to the attainment of this putative endgame – which is regime preservation and deterrence against an attack from the US or South Korea.

What North Korea has to its advantage is the mystery that shrouds its military capabilities, which affords Kim Jong Un political space because no one can calculate the damage he can wreck upon them if he so wishes. There is much that remains unknown about North Korea and its ballistic missile and nuclear capabilities. Technical intelligence gathered from North Korea’s ballistic missile tests provide the only data – largely unverified and hence the variances – on their capabilities.

Authoritative estimates suggest that the recently tested Hwasong-7 short-range ballistic missile has a range of 800 to 1,000 km; whereas the inter-continental range Taepodong-2 missile tested in 2012 has a range of 4,000 to 15,000 km. The KN-14 inter-continental range missile currently under development is estimated to have a potential range between 8,000 and 10,000 km.

While this may seem to some as if North Korea has working missiles that can reach Australia, India and even New York, these ranges are ascribed to these missiles based on extrapolations from the technical intelligence gleaned from ballistic missile tests, and should therefore be treated with at least some scepticism.

Moreover, the tests that North Korea conducted were not actual inter-continental ballistic missile tests, which involve testing whether the missile can carry their weapons into the atmosphere, manage re-entry and detonate upon reaching a specific target.

Furthermore there are three glaring intelligence gaps concerning North Korea’s ballistic missiles which impedes our ability to assess if they can credibly launch a successful strike.

One gap is the throw-weight, which relates to the size of the warhead that these missiles possess and determines how much destruction each can cause. North Korea’s May 15 missile test may be able to carry a nuclear warhead. However, that further presupposes that North Korea has been able to weaponise its nuclear programme, to transform crude nuclear devices into warheads small enough to be deployed by missiles. There are no signs of this as yet.

The second gap is the accuracy of these missile guidance systems, typically measured in CEP, or circle of equal probability. As an example, the US Navy deploys the Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile that has an estimated range of 12,000km, carries up to 12 warheads, and can land each warhead within 90m of its intended target. But there is simply no data on the accuracy of North Korea’s missiles.

A third gap is whether North Korea has access to high-grade material for the missile body, which is needed to ensure that missiles do not burn up when exiting and re-entering the atmosphere. Such material has been a key object in most UN sanctions.

Apart from missile technology, there is also little known about North Korea’s conventional military capabilities, except that its military is about 5 million strong and North Korea pours most of its government budget into defence – which amounts to about US$6 billion (S$8.4 billion), according to some estimates.

There have been suggestions of a North Korea link in the recent global cyberattacks. This is plausible because developing offensive cyber capabilities may give North Korea an asymmetrical advantage with the potential for disruption and intelligence gathering. For North Korea, the overwhelmingly antiquated nature of its conventional military capabilities also means that such asymmetric capabilities are pretty much all it has as strategic levers.

LIMITS TO CHANGING NORTH KOREA’S BEHAVIOUR

Any effective military strategy necessarily requires an accurate understanding of the adversary’s intentions. By failing to understand the adversary – in this case, North Korea’s endgame – any strategy will fail to leverage the basic motivations of the adversary.

The effectiveness of a military strategy is predicated on three factors: capability, credibility and communication. The Carl Vinson battle group clearly possessed significant military capability. However, the credibility of the US’ threat, despite evidence of President Trump’s muscular foreign policy evident in the Apr 4 strikes against Syrian military targets, was debatable at best, for any military action against North Korea can only be conducted with at least the tacit approval of Beijing. But why Beijing would agree to weakening an ally at its doorstep that provides useful buffer and poses a distraction to countries like the US is unclear.

Finally, the fiasco surrounding the deployment of USS Carl Vinson demonstrated a failure to communicate clearly to the targeted state of North Korea that the US was going to do something that would hurt North Korea’s interests.

PROBABILITY OF IRRATIONALITY CANNOT BE ELIMINATED

There is a seldom-discussed fourth factor: The susceptibility of the target state to being compelled or deterred. There are at least two schools of thought on understanding North Korean foreign policy behaviour.

On one end, encapsulated by US senator John McCain, who famously described Kim Jong Un as a “crazy fat kid”, North Korea is regarded as an irrational actor. The country has a historical habit of assassinating political detractors and enemies of the state. Past attempts include efforts to assassinate South Korean presidents and even the reportedly successful attempt on Kim’s brother Kim Jong Nam.

North Korea has also undertaken dubious military attacks that do not appear to have any benefit apart from testing how South Korea would respond. Recent incidents include the 2010 sinking of the South Korean naval vessel Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong island, killing two South Korean marines that same year.

On the other end, North Korea may not be as irrational as the first school thinks it is. Proponents of this school argue that Kim Jong Un and his father Kim Jong Il deliberately cultivated a reputation for irrational behaviour as a way by which to maximise North Korea’s limited leverage in international politics.

If policy makers hold to the “North Korea as irrational” school of thought, this then provides very little incentive to attempt to understand North Korea and decipher its endgame. A crazy North Korea means the international community has little, if any indeed, leverage through which to compel the former to cease its missile tests and deter it from conducting another nuclear test in the not-too-distant future.

However, even an accurate understanding of North Korea will not necessarily result in strategic success; simply because the probability of Kim Jong Un truly behaving irrationally cannot be eliminated. The element of chance means that any strategy – however well-thought through – holds within it the prospect of failure.

Finally, the deployment of military assets to the vicinity, whether for deterrence or compellance purposes, introduces an element of risk of miscalculation leading to a serious crisis. If not properly managed, such actions may result in armed conflict, an outcome which both sides would have wanted to avoid.

North Korea is unlikely to significantly change its behaviour any time soon; neither will the US likely back off or down.

So we can expect further provocation from North Korea and reactions from the US and other countries.

But we shouldn’t expect these reactions to produce measures that work unless these involve China or South Korea – the countries that hold bargaining chips that North Korea may be interested in.

Bernard Loo is associate professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.