commentary Asia

Commentary: Inequality looms beneath the shiny facade of Southeast Asia's growth

Income inequality in Southeast Asia remain stubbornly high, despite strong regional growth but addressing this issue and its causes, especially the rural-urban divide, can create a more sustainable development pathway for ASEAN countries.

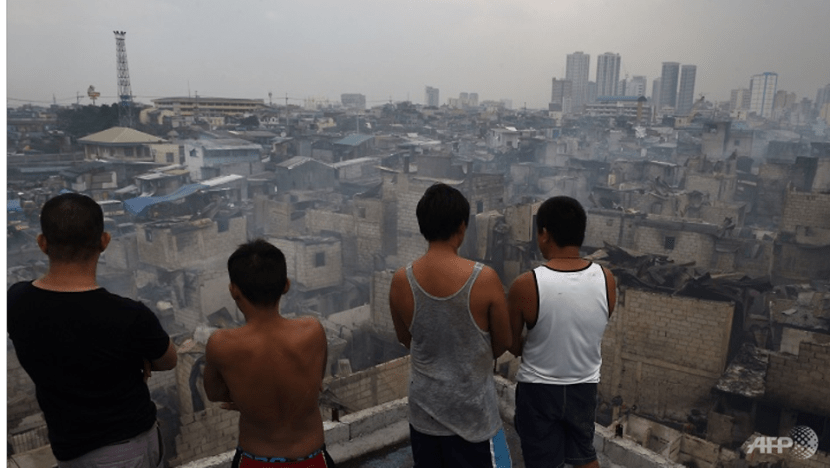

Residents watch as smoke billows from houses gutted by a fire overnight in an informal settlers area, near the south harbour port in Manila on February 8, 2017. (Photo: AFP)

Singapore is the 20th century’s most remarkable economic development story, and regional peers are hungry for equally transformational growth. So it comes as no surprise that Southeast Asia has produced remarkable growth in recent years. ASEAN’s GDP doubled between 2001 and 2013, outpacing the United States, EU, and all Asian countries besides China.

Projected 4.8 per cent growth for 2017 is indicative of continued optimism. ASEAN’s economic diversity, commitment to growth, and expanding workforce will provide a crucial advantage in the coming decades.

However, inequality remains stubbornly high. Governments may be imperiling economic and social progress by overlooking this challenge, in particular, the gap between rural and urban areas. While the strategy to compete in global manufacturing markets has compelled governments to focus on urban industrial infrastructure, rural development is becoming a political and economic necessity.

INEQUALITY IS UNEVEN ACROSS SOUTHEAST ASIA

In a 2016 address, Ong Keng Yong of Singapore’s Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) argued that ASEAN countries have made strides in eradicating poverty and hunger, improving healthcare, and protecting vulnerable groups. Asian Development Bank (ADB) statistics for the Asia-Pacific bear this out. Between 1990 and 2010, extreme poverty – commonly defined by an earnings threshold of US$1.25 per day – in this region fell by more than 30 percentage points. Furthermore, income growth for the bottom 40 per cent outpaced that of the population as a whole.

However, raising this earnings threshold to more realistically measure poverty in developed countries paints a less encouraging picture. At US$1.51, below which ADB declares a person “extremely” poor, poverty in ASEAN is high. It stands above 30 per cent in Laos, above 25 per cent in Indonesia and the Philippines, and above 20 per cent in Cambodia and Vietnam.

The GINI coefficient, a more comprehensive gauge of economic inequality, indicates a similar trend: ASEAN’s is 42 (40.5 adjusted for population size). Countries with high scores which signal high inequality include Thailand (48.4, in 2011), Singapore (46.4, 2014), and Malaysia (46.2, 2009). ASEAN’s inequality is lower than China’s (46.9) but higher than India’s (33.6).

While poverty is typically measured in monetary terms, other indicators reveal the hardships facing ASEAN’s disadvantaged populations: Health, education, gender disparities in labour markets, and access to services such as water, sanitation, and electricity. These challenges require a variety of policy levers beyond basic income redistribution; at the strategic level they necessitate a more robust commitment to narrowing ASEAN’s rural-urban development gap.

SOMETHING MUST BE DONE TO ADDRESS INEQUALITY

Economic inequality can hamper policy efforts to eradicate poverty, and limit the availability of capital for individuals to develop skills and nurture enterprises. In a way, inequality is “institutionalised”, perpetuated in part by insufficient social protection, regressive economic policies, and geographic favoritism in development. Inequality also restricts the emergence of a middle class that could boost consumer demand.

Global competition to attract manufacturing production is forcing newly developing countries to focus on low-wage manufacturing, luring low-skill workers away from agriculture. Yet, the chase to the bottom of the labour-cost continuum is exacerbating inequality. Furthermore, vulnerability to market fluctuations in certain sectors (consumer goods for instance) is compromising the development of a stable economic base, making growth “fragile”.

Addressing inequality ASEAN-wide is challenging due to varying levels of development across and within countries. In rapidly industrialising economies like Vietnam and Thailand, skilled workers are abandoning rural agrarian livelihoods and migrating to urban industrial centers. In more developed countries, wealth amassed through global financial and commercial activities is captured by urban economic and political elites, while rural areas fall further behind.

For these challenges, there is no universal policy prescription aside from high-level commitments to corrective resource allocation.

RECHARTING THE DEVELOPMENT PATH

The 2025 vision for the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) reveals how economic inequality may evolve in the coming decades. The AEC concept embraces regional integration to enhance global economic competitiveness, with ASEAN countries drawing on an effectively borderless market for factors of production like materials and labor.

This theory sounds very appealing but might not bear out practically. While enabling worker mobility broadens access to economic opportunities, many of ASEAN’s lowest-income workers remain immobile due to relocation costs, vulnerability to uncertainty, and reliance on place-based community or family ties. Those who live in rural areas are also geographically isolated from higher-value-added manufacturing jobs that accumulate in urban areas.

Aside from economic risks, the widening rural-urban development gap could threaten political stability. Ignoring the plight of the rural poor comes at a political risk, particularly in countries with largely unified rural voting blocs like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. The economic struggle of rural low-income and working class citizens can foment destabilising political movements like those recently seen in the Philippines, Europe, and the United States.

The bottom line is while the AEC vision commendably prioritises inclusive growth, only domestic political will within ASEAN countries will determine whether all citizens benefit.

Initiatives to improve education, services, and living conditions require not only a strategic vision that complements broader development goals, but also consistency of commitment across political and business cycles. Longer-term programs should target rural development, including the promotion of sustainable farming practices and the application of leading-edge technologies to improve crop yield and improve food security.

Notwithstanding the environmental and social risks of agricultural industrialisation, technology-based productivity enhancement should also be prioritised. Many such innovations already target “smart city” programs, but an ASEAN-specific “smart farms” initiative may be needed.

START WITH THE UNIT OF THE HOUSEHOLD

Singapore’s early poverty alleviation program provides instructive examples in visionary leadership. For example, public housing was a social and economic building block throughout the country’s decades of rapid development, improving public health and providing a vehicle for household-level investment. It also enabled a coordinated land use regime that became a cornerstone of sustainability.

However, like many global cities Singapore continues to struggle with inequality as incomes among the wealthy continue to rise – and with them the cost of living. Singapore’s inequality challenges are those of a highly developed city-state, whereas the rest of ASEAN confronts inequality as manifest in part through the rural-urban development gap.

While the two cases are not perfectly comparable, Singapore’s multi-faceted and visionary strategy is worthy of emulation when refining the ASEAN development template to address the root causes of inequality.

ASEAN’s 21st century call-to-action should be the pursuit of higher development standards and their normalisation across rural and urban areas – on issues like personal security, health, education, housing, and basic services. A robustly financed commitment to these issues can advance the cause of inclusive growth and social progress.

ASEAN must not forfeit the latent potential of its citizens by ignoring inequality.

Kris Hartley is a Lecturer at Cornell University and a non-resident fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.