As a measles epidemic rolls through the Philippines, blame falls on bungled vaccination programme

The Dengvaxia program was rolled out to nearly one million people, mostly children, despite side effect concerns. (Illustration: Kenneth Choy)

MANILA: Six months into this measles epidemic and the doctors and nurses of San Lazaro Hospital are exhausted. For months they have been on the frontline of a national crisis.

On this day in the paediatric ward there are nine young children, some of them small babies, being treated for the highly infectious disease. Covered in a thick rash, they squirm and scream in discomfort, their mothers emotional and stressed.

Measles can be deadly, with pneumonia a common complication. And it strikes fear in the families who bring their little ones here.

“Most of them are very worried. They don’t know what to expect,” said Ailyn Adao, a senior nurse at the hospital.

“They’re hoping that after the treatment they’ll go home happy, but of course not all of them do. Some of them go home with heartbreak.”

The statistics paint a grim picture of the magnitude of the Philippines’ measles troubles. The number of cases has exploded in 2019. So far this year, there have been more than 35,000 recorded cases and close to 500 deaths, a 600 per cent increase compared with same time last year.

READ: Measles outbreak declared in Metro Manila: Report

At its height, 600 cases were emerging on a daily basis. Even last month, that number was 60, according to the Department of Health (DOH). This in a country with ambitions to have no measles cases on the back of an expansive public health outreach programme.

San Lazaro Hospital has been the epicentre of this epidemic. It is the national referral centre for infectious diseases, and at the peak of the outbreak in February, waves of infected children - hundreds of cases at a time - were overwhelming its three paediatric units.

“There were three children in each hospital bed. Parents were sleeping under the bed. Tents were set up outside. We were a boat, and we were filled up,” said the hospital’s spokesperson, Dr Francis de Guzman.

Crucially, most of the children at the hospital had never been vaccinated against measles, an entirely preventable disease. The situation is most complicated for the youngest children.

“We were alarmed. We were seeing children less than 6 months old developing measles. It means the mothers did not have immunisation either,” de Guzman said.

“We could have prevented these deaths.”

Part of the blame for the epidemic lies with the DOH, which admits to having let immunisation levels “drop dramatically” over the preceding years. Undersecretary Dr Rolando Enrique Domingo says complacency had gripped the department and its efforts were not penetrating effectively at the local level.

“We relaxed a little. Maybe the effort wasn’t there. Maybe the health department wasn’t exactly in tip top shape. It was very fragmented. There were problems in the system and there were problems with people getting complacent,” he said.

READ: Measles threat looms in Philippines as trust in vaccines declines: Health officials

But there were bigger forces at play, which have dramatically undermined the public’s confidence in all vaccinations. As many countries around the world grapple with vaccine hesitancy and the influence of the ‘anti-vaxx’ movement, the Philippines itself opened the door to widespread skepticism and fear.

It came on the back of an entirely different vaccination the department started rolling out in 2016. It was a seemingly breakthrough solution to the mosquito-borne virus dengue - sometimes referred to as “breakbone fever” for the agony it can inflict upon its victims.

The dark clouds had been rolling in for three years. This measles outbreak - and its deaths and pain - was the storm hitting.

INJECTING THE NEEDLE

The story of Dengvaxia is encircled by political point scoring and contentious science.

Speak the word Dengvaxia among parents of school-aged children in the Philippines and the anger and confusion about this vaccination becomes clear. The dengue vaccine is the sole reason for many that their children have not been immunised against any disease since its rollout.

For the Philippine public, however, this vaccine was meant to be a solution: A world’s first answer to a dangerous and deadly virus. On April 4, 2016, it was unveiled by the government as such.

A schoolgirl in Marikina City was one of its first beneficiaries. The young girl, surrounded by health officials with news cameras rolling, winced as her left arm was injected with Dengvaxia by the nation’s health secretary at that time, Janette Garin.

"It is painful to admit there are people who get sick and die. The government can't close its eyes. We can't turn our backs on you when you need us,” Garin said then.

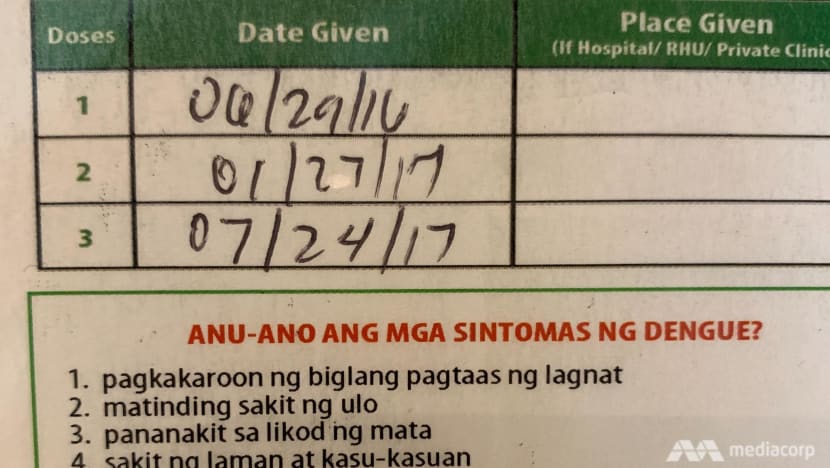

Over the next 18 months, nearly one million people - mostly children - would receive the same jab. The plan was for recipients to receive three injections over a 12-month period, to help safeguard against the endemic virus.

But from the start, the strategy was questionable, the preparation sparse and the cost astronomical.

THE WARNING SIGNS

Dengvaxia is a product of French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi Pasteur, which had spent the best part of two decades trying to develop an effective and marketable vaccine. Philippine health officials had been closely watching the development of the drug for years.

In October 2015, the company made a formal application to the Philippine government under the helm of President Benigno Aquino, who was coming to the end of his term. Indeed, election season would soon be underway across the country and Aquino’s Liberal Party was pushing hard for the victory of its presidential candidate Mar Roxas.

Sanofi wanted Dengvaxia included in the Philippine National Drug Formulary, a list of approved essential drugs. Janette Garin put the programme on a fast track. Just ten days after concurrently becoming the head of the Food and Drug Administration, the body that could rubber stamp its use across the country, she would accept Sanofi’s invitation to view its facilities in France and allegedly discuss the price of a huge order for the drug.

By the end of the year, a budget of about US$75 million had been approved to spend on Dengvaxia and the orders placed.

This amount was more than the combined budget for the country’s entire vaccination programme, including for measles, despite dengue not being one of the top ten fatal diseases in the Philippines.

The initiative did not receive congressional approval and the procurement of the vaccines circumvented the DOH, and was instead left to a Manila children’s hospital to expedite the purchase.

At this time, the vaccine was still in clinical trials. And there were concerns about its efficacy and safety. Still, the Philippine government was about to administer the vaccine to nearly one million children.

Medical experts, including epidemiologist Dr Antonio Dans, penned a letter to Garin to raise “significant issues” before the programme began. The vaccine showed “signals of harm”, and “systemic side effects”, he said in the letter co-signed with eight others.

The vaccine “may cause public furor, especially if any children die," it added.

The World Health Organisation issued its own warnings, saying Dengvaxia could prove ineffective or harmful to those who had never been exposed to the dengue virus before. It did, however, give a conditional green light to the vaccine later in 2016.

There were concerns that if children were exposed to a strain of dengue in the year after their first shot and before the course was completed, the original vaccination could act as a primer, making the second infection far more dangerous. This is due to the nature of the dengue virus, where a second incidence can be much worse than the first.

Still, the project gathered speed. A preparation, public awareness and training process that could normally be expected to take one or two years was done in 26 days.

The premise for the fast implementation was an imminent dengue emergency, but some have claimed the looming election was also a factor, with the initiative seen as a potential vote winner.

Three regions were handpicked for the project, all key battleground - and typically poor - areas that candidate Roxas hoped to win. Important political figures like governors, election candidates and even the president himself were on hand as Dengvaxia was dished out to students in yellow shirts, the colour of the Liberal Party.

“It was electioneering,” said Dengvaxia project manager-turned-whistleblower Dr Clarito Cairo, who was parachuted into the role from a different section of the DOH.

He claims none of the potential warnings or side effects were communicated to parents of the hundreds of thousands of children lined up in their schools for vaccination – partially because some people involved in the programme were unaware of them.

“We never told the implementers about the four adverse effects. Because it was not written. It was not known. That was another red flag,” he said.

“If we’d known there were adverse effects, we should have relayed that to the patients or the parents of the children. But there was no instruction whatsoever. So the preparation was not good enough.”

In November 2017, Sanofi issued new advice on the use of Dengvaxia which would deliver a death blow to the entire scheme in the Philippines.

"For those not previously infected by dengue virus ... the analysis found that in the longer term, more cases of severe disease could occur following vaccination upon a subsequent dengue infection," it said.

"For individuals who have not been previously infected by dengue virus, vaccination should not be recommended.”

Within a week, the entire project had been suspended by the DOH. But the admission by Sanofi had sparked concern in the community and started a widespread suspicion of all vaccines and the health system itself. It lingers to this day.

VACCINES AS ‘WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION’

The DOH estimates that 10 to 15 per cent of those who received the vaccine might never have been exposed to dengue before - approximately 100,000 individuals. But with no reliable rapid test to determine who had or had not been infected with dengue before, this meant many people were suddenly on edge. The DOH, part of the architecture of the Dengvaxia project, found itself under siege. “When they announced the possible risks of dengue, it was taken out of context and suddenly included so many other diseases,’ said Undersecretary Dr Rolando Enrique Domingo.

“This was weaponised against vaccines. The vaccines were being shown as weapons of mass destruction in memes. Can you imagine if you were an anti-vaxxer and then this happened? It’s like a dream come true.”

The saga was splashed across the country’s newspapers and social media timelines. Public faith in vaccines plummeted, from 93 per cent who would “strongly agree” that they were important in 2015 to just 32 per cent in 2018, according to a study by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

READ: Takeda dengue vaccine meets main goal of trial

READ: Undeterred by Sanofi's stumble, Takeda takes similar path with dengue shot

“It is rarely one incident alone which can fuel such a dramatic drop in confidence. What is different is how far and how quickly messages can spread around the world with new social media,” said the study’s author and director of The Vaccine Confidence Project, Prof Heidi Larson.

Suddenly public vaccinations ground to a halt in schools and community health centres. Fear gripped communities and health workers were demonised.

A 16-month-old baby at San Lazaro suffering from measles was, for example, never protected because her grandmother actively hid her from routine vaccination drives out of fear of Dengvaxia.

“There were people who went from house to house, but I hid my grandchildren and youngest child out of fear. I was afraid that they might get vaccinated. It was for measles. But I regret now not letting them get the shots,” the woman told CNA from the hospital ward.

It’s a story echoed by hospital spokesperson de Guzman. “With the house-to-house nurses, they would shut the doors in their faces,” he said.

“They would let the dogs loose on the nurses. It was traumatic for them.”

‘A LONG TIME’ BEFORE HEALTH DEPARTMENT LIVES THIS DOWN

As the DOH attempts to restore its credibility, it has been forced to concede that the department made mistakes in the way it implemented the Dengvaxia project. “It’s really disappointing, it’s sad and it makes you angry that maybe we should have considered it a little more before we did this,” Domingo told CNA.

“This department will always be the Dengvaxia department. It will take a long time before the Department of Health lives this down. The trouble is when you lose trust in the Department of Health, the whole system falls apart.

“It was very painful for the health workers who helped give out the vaccines. They changed from the most loved members of the community to the most hated and persecuted.”

The reason for that hatred is because in the wake of the initial rollout of the Dengvaxia programme, allegations were made linking it to illnesses and death.

Such claims have been strenuously rejected, with the DOH and Sanofi denying any responsibility. Any illnesses or deaths were coincidental they say – a position that has been made at various enquiries and investigations already.

“These are a million kids, and when you have a million children, at every age, you lose some to natural causes,” Domingo said. “Some are going to have leukemia, some kids are going to have heart disease and some kids are going to die from brain tumours or pneumonia. When all of this blew up everyone started blaming the vaccine. There was some irrational thinking.”

Still, the issue has been kept in the headlines, with the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) vocal in contesting the position of the DOH and Sanofi. The PAO, which provides legal assistance to those who cannot afford a lawyer, has been pursuing a link between unexpected deaths and illnesses and the drug.

The PAO says completed autopsies on alleged Dengvaxia victims point to a pattern in a number of deaths among children who received the vaccine, with evidence of enlarged organs and significant internal bleeding - common symptoms of dengue. The PAO suggests this is a strong causal link to the vaccine.

Domingo says he has empathy for those who have been affected by the immunisation programme, but the scientific evidence does not support such claims.

“It’s so sad. I try to keep a scientific mind, but when I see the mothers it’s easy to get angry. The fear is genuine. These were a million kids and a million mums. Not all of them are going to forget it after one year,’ he said.

Of 154 recorded deaths among children who received Dengvaxia, the DOH says 19 of them died from dengue, and the others were unrelated causes.

Still, the controversy continues. Elvie Ligeralde says she never gave permission for her two children to receive Dengvaxia. They were injected anyway and within days, she says, her daughter had a fever and was later admitted to hospital.

“I rushed her to the ER because she could not eat, she was so pale and she could not taste her food. The worst thing that really scared me was that she couldn’t stand; her knees didn't have strength,” Ligeralde said.

Dr Cairo, while working on the project, says it was not uncommon for children to be included in the vaccination sweeps, even if their parents had not approved it beforehand, or been given sufficient information about the drug.

While Ligeralde’s children have recovered, she has been driven to support others going through a fearful and confusing period.

“We are urging the Philippine government and Sanofi Pasteur that it’s about time. Have mercy on our children. Our children are not lab rats,” she said.

Together with her group, United Parents Against Dengvaxia, Ligeralde is continuing a push for more information about the vaccine. And they want to unlock funds - returned to the Philippine government by Sanofi to refund the cost of unused vaccines - for Dengvaxia recipients. The funds remain stalled in the national Senate and Congress.

‘THIS CAN ONLY HAPPEN IN THE PHILIPPINES’

The debate, discussion and doubts about Dengvaxia more than 18 months after the programme was suspended have resulted in heightened, long-term concerns about vaccinations.

The potential wider negative impact is something acknowledged by the United Parents. While they are still campaigning on the Dengvaxia issue, they have made it clear that they do not have a wider anti-vaccination agenda.

Indeed, as the measles epidemic took hold, the United Parents say they began accompanying nurses and health officials to ease concerns as they administered measles vaccines in the community.

Ligeralde says the ripple effects of what happened with Dengvaxia are unfortunate. “We want to try to ease the worries of the public and convince them to trust the measles vaccine. It will take some time before trust can be built again between the public and the DOH,” she said.

“The only thing we want to do is to save the children.”

While Sanofi did not respond to an interview request, the company has consistently said that it has always been transparent with its drug and its possible side effects. It denies it concealed any risks from the public.

Dengaxia continues to have defenders in the Philippine community, with some lamenting the damage the “name calling” and “witch hunting” has caused to public health, particularly when it comes to confidence in other vaccines.

Dr Raymundo Lo, a pathologist and former deputy executive director of Philippines Children’s Medical Centre - the very same hospital that originally procured Dengvaxia - says he would like to see it brought back to the Philippines.

“Anything that can control a serious epidemic is definitely welcome. By all the parameters, Dengvaxia satisfies that,” he told CNA.

Dengvaxia is now licensed and available in a range of countries, including the United States. It is only to be administered to those who have had exposure to the dengue virus before, a precaution not afforded to the children in the Philippines during the mass-vaccination programme. And it is a strictly prescribed medicine, not part of a mass vaccination initiative.

A MEASLES MESS

Irrespective of the situation in other countries, the Philippines is still counting the cost of what happened, especially in terms of people deciding they cannot trust vaccinations.

The DOH says it has thrown more than double its normal resources directly at the measles epidemic this year, even at the expense of other health initiatives. The World Health Organisation has stepped in to build capacity, but concedes the response is simply a “fire fighting approach”.

Meantime, as Dengvaxia continues to hog the headlines with ongoing legal cases and senate enquiries, Domingo is worried that the recent progress made with measles immunisations is a temporary success. “We dropped everything and just focused on vaccinations,” he said.

“When this dies down we don’t want a hard time getting them back again. It has to be reinforced. The fear is working for us now but you need the same energy every year,” he said.

The Philippines has been far from alone in contending with a serious measles outbreak this year. The disease has reared its head across the world - the number of cases globally in 2019 four times higher compared to last year. Regionally, parts of Thailand and Malaysia have also been severely impacted.

Misinformation has played a major role, but so too have health systems failing to maintain necessary standards.

It was easy to predict in the Philippines, according to Dr Gundo Weiler, the representative of WHO Philippines, and it could have been easily controlled. “We’ve seen consistently low coverage of routine immunisation programmes. Basically, the epidemic didn't come as a surprise,” he said.

READ: Sanofi wins FDA approval to sell dengue shot in parts of US

To ensure herd immunity for measles, coverage rates in the community should be 95 per cent. The Philippines was operating at 70-80 per cent for years.

With the controversy over Dengvaxia, the system was further punished for its years of complacency and ineffective programmes. Domingo describes the situation like “building this mound of dry leaves and all of a sudden it becomes this gigantic mound”.

“We just do the best we can to save the dying ones. But it’s not in our hands, especially with the severe cases,” said Ailyn Adao, the senior nurse at San Lazaro Hospital.

“The parents need to be equipped with enough knowledge. They don’t need to be scared. Without the vaccines, you see the outcome is not good.”

While the current measles situation is close to being under control, the next challenge is brewing: The country is now bracing for dengue season.

The fallout may just fuel the vaccination debate and the fear that swirls around it in the Philippines even further. The nurses at San Lazaro are standing by for whatever comes their way.