Singapore should have minimum wage, says economist Lim Chong Yah

The former National Wages Council chairman goes "On The Record" about what led to his thinking on income inequality and his arguments for why the Government should still consider implementing a minimum wage.

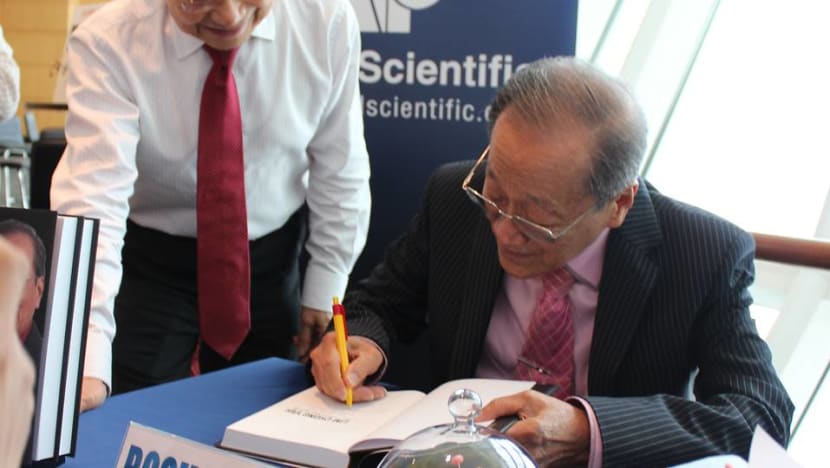

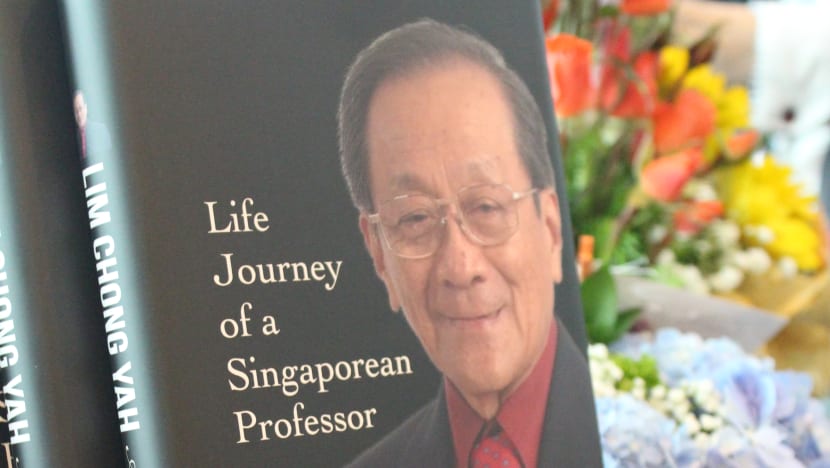

Former chairman of the National Wages Council Lim Chong Yah. (Photo: World Scientific Publishing)

SINGAPORE: Eminent economist and academic Lim Chong Yah is perhaps best known for serving as chairman of the National Wages Council (NWC) for almost three decades.

In 2012, he made headlines for suggesting what has been dubbed “wage shock therapy” - hiking the pay of the lowest-paid workers by 50 per cent over a period of three years and a voluntary freeze, for three years, on further pay increases for those earning more than S$1 million per year.

His proposals were met with mixed responses.

Five years on, he stands by them, and maintains that the Government should consider implementing a minimum wage.

Lim recently crystallised his thoughts in the book Lim Chong Yah: An Autobiography, Life Journey of a Singaporean Professor. In it, he also describes his childhood and the seeds of what led to his thinking on income inequality.

He went On the Record with Bharati Jagdish, and spoke first about growing up in Malacca, where his father was a shopkeeper, and what it meant to grow up without his mother.

Lim Chong Yah: In my childhood years, my mother passed away suddenly when I was eight years old. So, I had a tough time having to look after myself without the benefit of a mother. That could have affected my attitude to life later on. Life then was very tough, particularly during the Japanese Occupation of Malaya. During the occupation, we could not export our rubber, our tin or other products, neither could we import, because there was the allied blockade of Malaya.

There was a food shortage, a shortage of everything, and it may have contributed to make life very, very tough for all of us during that period of our own local history.

Bharati Jagdish: I understand you had to farm rice, tapioca and vegetables to help your family earn an income.

Lim: Yes, I learnt farming, or what you call today, “horticulture”. I learnt to survive. I used to call it the “university of hard knocks” that I was thrown into, without having applied to join.

Bharati: Would you say you are better for it?

Lim: I think so. I’m steeled by it. I thought I later became a stronger person, hopefully, a better person.

Bharati: To what extent is this the factor that led you to talk about issues such as income inequality?

Lim: It must have. It must have. I saw a lot of people along the streets of Malacca, and often because of the lack of food, they developed paunchy stomachs. A few days later, I could see them one by one dropping dead. Dead. That gave me - a little boy - a very, very tough impression. Why should we human beings establish ourselves a world where people have to starve to death? Was there a way out? It kept bothering me throughout my life. And when I studied economics, that became uppermost in my mind.

Bharati: I understand you had the potential of getting a cabinet post in the Malaysian government, but you chose instead to go down this path of academia. Why?

Lim: When Tun Abdul Razak was the prime minister, and Tun Tan Siew Sin was the minister for finance, they invited me to return to Kuala Lumpur with the view to become a cabinet minister, a minister for land and land settlements, which meant new villages. I was very apprehensive. I know my lack of ability to be a politician.

Bharati: What specific abilities did you think you lacked?

Lim: I thought you need people who are made of stronger and sterner stuff to be in political leadership, particularly at that time. I thought I did not qualify. So I disqualified myself from that very thoughtful invitation.

Bharati: Do you regret that at all?

Lim: I always thought that I might stand a chance to be an educator, a writer, and maybe, maybe a minor professor to change the world slowly that way.

IMPROVING THE CPF SYSTEM

Bharati: You’ve tried to do this in some ways through your work. In 1986, you set up a study group on the Central Provident Fund (CPF) and you did a report to analyse the CPF withdrawal age. That was a result of the adverse public reaction to the Government's suggestion in 1984 to increase the age of CPF withdrawal from 55 to 60. In your report, you said the withdrawal age should remain at 55. You also said that there ought to be an insurance policy for catastrophic illnesses - we are seeing that to some extent today - and you also had a section on the implementation on the minimum sum scheme.

Some Singaporeans still question the CPF scheme though. It’s for retirement funding, but those who have financial problems in the here and now often say they want access to these funds. In fact, some of our listeners say there’s no point thinking about funding their retirement when they can’t make ends meet today.

Lim: That is not the purpose of the CPF. When the CPF started off, the objective was for retirement. It was a kind of Singapore pension fund. Of course we need to have old age funds. Which developed countries do not have that? Even developing countries have old age funds. There are problems with pension funds in some countries however. It might sound good, but may not really be.

Maybe I should mention the Chinese pension fund for academics. I am told by one of my colleagues who retired here. He said that in China, they have to retire at a certain age. But when they retire, the academic would get the same pay, their last-drawn pay, throughout their lives. That's interesting and shocking news. That means your current pay would be kept purposely low. It's a rather unusual arrangement. That’s why I am in favour of our system. Improve our system. Keep our system, but improve it.

Bharati: What improvements can you suggest at this stage?

Lim: In my view, it may not be that satisfactory as a real pension programme because the sum for quite a lot of people would be still very, very minuscule; very, very small to take care of their old age. That is the snag in that report. Look into the adequacy of the minimum sum for those who could not contribute large sums of money so they can get higher annuities.

Bharati: How do you think this can be achieved?

Lim: You need another study group to look into this.

Bharati: Don’t you have any ideas?

Lim: I have my own ideas, which if I have the opportunity, I would develop.

Bharati: What are your ideas?

Lim: For the time being, I would rather keep it under discussion between myself and some of my colleagues.

Bharati: Why don’t you want to disclose your ideas at this point?

Lim: It's still too early. I am still contemplating, studying the best possible option, being quite unhappy that the annuities are still very, very low for a large number of people. They can be just quite meaningless.

FAITH IN GOOD GOVERNMENT

Bharati: Some analysts have commented that there is too much of a strain on CPF funds. The money can be used for housing, for education, which some see as a good thing, but others see that as a reason for the funds dwindling and hence not being sufficient for retirement. What is your standpoint on this?

Lim: Housing is a great asset, a great development for us. I think that is one of our greatest achievements - public housing. A huge number of people, a large percentage, probably about 80 to 90 per cent of our population are living in public housing, subsidised public housing. And the Government in the past 10 or 20 years or so, has put in more and more money, rightly so, to upgrade the environment, and to upgrade the public housing programme. So much so that it's difficult to differentiate between public housing and expensive private condos - and CPF has played a very major critical role in raising money for such a development to take place.

Bharati: You say housing is a great asset, but today the Government has pointed out that at the end of the 99-year lease, the homes may just have to be returned to the State and that as flats near the end of their lease periods, naturally, their prices will come down correspondingly.

Lim: Yes. I don't think the authorities would just take back in that kind of ruthless and uncaring manner. I doubt very, very much so. I think there is no need to worry about that.

Bharati: Why are you so confident that this is the way it would pan out?

Lim: There are no indications to the contrary.

Bharati: You have that much faith?

Lim: Yes, that much faith in good government. We have a good Government, and we have to ensure we have good and responsible government.

ROOM FOR RESPONSIBLE DIFFERENCES OF VIEWS

Bharati: You’ve had your own run-ins with the Government though. And when you declined to elaborate further on your ideas to improve CPF earlier, I was reminded of something you mentioned in your book. You talked about the problems you had in publishing the CPF Study Group report in the 1980s.

Lim: Yes, I couldn't understand it myself. Why one minister rung me up and said it's better not to publish the report. I couldn't understand.

Bharati: You wondered what could have caused them to be sensitive about it. But you took matters into your own hands and you published it anyway.

Lim: Yes, because one minister passed the buck to another minister, another minister passed the buck to another minister. I decided just to publish it, as a special volume of the Singapore Economic Review publication, because I was the editor and it was a publication of the Economic Society of Singapore.

I was the president so I decided to use that vehicle to publish the book, partly because a lot of the book had already been published in The Straits Times. One very resourceful journalist somehow got hold of a copy of the report. We didn't even know. We in the university didn't even know how she got it. Then it appeared in the front page of The Straits Times almost daily. Partly because of that, we took the initiative to publish on our own.

Bharati: Now that you look back, why do you think the Government took objection to publishing it first?

Lim: It's an enigma! I do not know. A complete misunderstanding, or maybe ultra-sensitivity? I am not so sure.

Bharati: This was not the only time something like this happened to you. There was another book you wrote with a few others, Policy Options for the Singapore Economy. The Education Ministry was against your publishing that book as well.

Lim: That book, when it was written, was sent to many ministries. I thought that maybe I should show different chapters relevant to different ministries. Some of the civil servants would reply in writing. Sometimes just by telephone and say: “Congratulations, it's a good chapter. We have no amendments to suggest.” But there was a call from MOE suggesting that we should not publish. Up to today, I do not know the reason, nobody told us the reason. I suspected there were things on which they didn't agree with me.

Bharati: Such as?

Lim: I was proposing a compulsory education system. At that time we didn't have compulsory education.

Bharati: Today we do.

Lim: It came from the book. Actually, the then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong invited me to the Istana for lunch and he said congratulations, we have agreed to introduce your idea of a compulsory education system. So he gave me a very simple yong tau foo lunch. I still remember that. So it was good enough to invite me to lunch. But that was a lapse of about 20 years from the publication.

Bharati: You have said that you were not expecting consensus for your suggestions and you believe differences in views are normal. But doesn’t it seem as if in saying, don't publish this book, they were afraid of the ideas being discussed openly. How did it feel to have your ideas suppressed and to only be thanked for some of them 20 years later?

Lim: I don't know. I am an academic living in a democratic society. In a democratic society, I strongly believe that we should have some room for responsible differences of view, responsible discussions on subjects that the country faces.

So I just exercised my responsibility by publishing anyway. It doesn't mean that whatever you say, whatever you wish, should become policy. I think that is fallacious thinking. You express your views. That doesn't necessarily mean that that must be the view by the Government.

Bharati: But the fact that there were attempts to ensure that your ideas were not made public ... the publisher in this case was McGraw-Hill, and you had signed a contract, but even they wanted to pull out. In your autobiography, you said that your purpose in bringing out the problems you faced in getting your books published is not to show that you had been proven right when the Government accepted some of your suggestions, but to highlight how sensitive it was to make public policy suggestions.

But it’s concerning that there were attempts to suppress the views.

Lim: At times, probably with hindsight, there was a lot of excessive sensitivity on differences of views on important matters. I was concerned, but we have evolved, we have changed, there is much less Government trying to tell us what not to think about, what not to say. Very much less. We have improved with the years.

Bharati: There might be much less of that today, but some feel it's still not good enough. To what extent do you believe there still is a culture of fear of being shut down by the Government?

Lim: I hope the fear would disappear with time.

Bharati: It can only disappear if the Government sets the tone for it. What do you think needs to happen for the Government to realise it needs to engage more openly with academics and activists in society and to be open to ideas that oppose its own, that these ideas could actually have some merit?

Lim: It really depends on your concept of democratic society. There is no doubt we have an electoral democracy. Except we should also, in my view, allow enough room for interchange of views. They may not be the same views, but in the last five to 10 years, I feel that the Government goes out to seek views. In a very controlled manner, but still, having said that, there are certain issues we should not deal too much with.

I agree completely with the Government on matters of religion, matters of race - we should be much, much more careful.

Bharati: Careful sure, but if we are too careful, if we don't talk more openly about such issues, how can we truly resolve the underlying problems?

Lim: But it can go out of control. It might contribute to destabilise our society and create disharmony.

Bharati: But why not work towards discussing differences, even on those subjects, responsibly, rather than avoiding deeper discussions on those subjects?

Lim: Such issues, very sensitive issues, can go out of control. If there is discussion, they should be done in a much more discreet manner, and contribute to racial and religious harmony and understanding, tolerance and stability.

Bharati: Of course, hate speech should be arrested immediately. But if there is no honesty in discussion, which is the risk if you control the discussion too much, what is the point?

Lim: We can, in a very controlled way, among certain responsible sections of the population. They can discuss, bring up those issues among themselves. They can talk and discuss, but for a public discussion on religion, I do not think we have reached that level where we can talk freely without…

Bharati: You don't trust Singaporeans to be able to do this?

Lim: I trust all Singaporeans but freedom has a limit, and the uppermost concern is for the public good. If we talk far too freely, we might say bad things about another person's religion, and we might end up having inter-religious problems in the country.

Bharati: As I mentioned earlier, of course hate speech should not be allowed, but why assume that's the way it is going to go?

Lim: It's a preventive, preemptive measure; a precaution.

Bharati: Some activists have said that too much of that may not serve us well in the long run in terms of creating a deeper understanding.

Lim: I am not quite sure. I still think with racially, religiously sensitive issues, there must be limits but a topic like minimum wage, I think it should be and it is discussed quite freely and openly.

Bharati: Beyond race and religion, you mentioned how the Government has been making an effort to do more public consultations and dialogue sessions, but some still feel that all this is like a "wayang", paying lip service, and that their ideas are not taken seriously. What do you think?

Lim: I really believe that it’s fallacious to think that whatever people say should become public policy. People should reconsider that expectation. It reminds me of a story of people praying to God. They say: "You know I pray to God for this and for that, but that is never granted." If God were to grant the wishes of everybody, there would be pandemonium. Some people may say: “Dear God, could you remove the eye of my neighbour. He is nasty, he is very cruel.”

STANDING BY WAGE 'SHOCK THERAPY' AND MINIMUM WAGE

Bharati: You have made suggestions over the years that have not been taken up yet, even though they made headlines. In 2012, you suggested hiking the pay of the lowest-paid workers earning less than S$1,000 per month by 50 per cent over a period of three years. You also suggested voluntary restraint, for three years, on further pay increases for those earning more than S$1 million per year.

Lim: My intention is to have growth with equity, which is to have inclusive growth. In technical terms, the Gini coefficient, which is used to measure income inequality, should not be allowed to deteriorate too much. So at that point in time, when I raised that issue, it was deteriorating to a fairly uncomfortable level.

Having said that, the Government has taken quite a lot of measures to transfer income, a large number of measures - in one form or another - to help the lower-income groups, so much so that our Gini coefficient has improved a lot.

Bharati: In fact, the Gini coefficient went down from 0.463 in 2015 to 0.458 in 2016 - Singapore's lowest score in 10 years. So do we still need those measures?

Lim: But there is much to be desired. It is still high if you look at the Gini coefficient without the Government interfering through taxation and through transfers.

Bharati: The figures I’ve given you don’t take into account Government transfers and taxes. The numbers are 0.409 in 2015 and 0.402 in 2016 after accounting for transfers and taxes.

Lim: We should not ignore the numbers before taking transfers and taxes into account. Because if the gap between two is wide, it means two things: People depend on the Government for transfers and for support. Secondly, you have to increase taxes and find other sources of revenue, which can be very burdensome to society as a whole and will make our economy uncompetitive. My suggestion is - approach it direct.

Bharati: This year, the NWC recommended an increase of S$45 to S$60 for low-wage workers earning a basic monthly pay of up to S$1,200.

Lim: NWC does not (and wisely so) use the term Gini coefficient because it's difficult for the general public to understand, but the objective is the same. They try to raise the incomes of the lowest-income groups, and in a very flexible wage guideline system.

Bharati: But is it too flexible? Will companies really comply unless they are unionised companies or public sector entities?

Lim: That is the problem. The problem of implementation. The compliance rate is very low. That's why I came up with the minimum wage proposal.

Bharati: Which the Government is against.

Lim: I hope the Government would change its mind. I still think we should have it.

Bharati: But things have changed since you called for a minimum wage here. We now have schemes like the Progressive Wage Model which applies to the security, cleaning, and landscaping industries. What do you think of this model?

Lim: As long as it is not very rigidly implemented. We should still leave a lot of room to management to manage the payment system. If you do it too rigidly, it might not be as preferable than to have a much more flexible way.

Bharati: But you just agreed that if any scheme were too flexible, there would be a problem with compliance.

Lim: Minimum wage is different from the compulsory payment of wages when people acquire certain qualifications. Are they relevant? Do they raise the productivity of the company? If they do, so be it. If they don't, do you still want to give them wage increases by law? So there needs to be some flexibility in such schemes as the Progressive Wage Model.

Bharati: Why do you stand by minimum wage considering these other models that have been introduced and the arguments against minimum wage have been spelled out several times by the Singapore Government? That it could increase the cost of production, could negatively impact the economy, it might actually result in a lower rate of employment because companies may fire some workers and divert their wages towards funding the minimum wage for the remaining workers. And it could cause companies to have reduced profits or even go bankrupt?

Although several studies have shown that none of this has happened in several countries that have implemented the minimum wage, the Government here maintains there are better options than minimum wage.

Lim: One can discuss the minimum wage issue until kingdom come. There are pros and there are cons. Most nations in the world, developed countries in particular, have introduced the minimum wage system. There were studies showing that with the introduction of the minimum wage, it would not damage the economy, provided the minimum wage level is linked to the national productivity level. In other words, it cannot be too high, neither should it be too low that it becomes irrelevant.

In our case, we are very blessed that we have the NWC that can study whether we are going too far in having the minimum wage.

If it's say, S$1,000, how many people would be affected? Preferably, the minimum wage should be implemented at a time when there is a booming economy than when there is fear of a slowdown or recession. The timing is important. The quantum, too, is important.

Bharati: You say it ought to happen at a time when the economy is good, but what happens if the economy turns bad? The minimum wage may not be sustainable anymore.

Lim: That’s why one mustn't put the minimum wage too high. That can create unemployment. These things have to be discussed.

Bharati: How do you guard against wage stagnation?

Lim: The NWC needs to study this regularly. We are a command economy after all, and the firms in the public sector and in unionised companies in the private sector will follow the guidelines even if it’s not legislated. The other companies have to consider that they would lose their workers, if all the other companies, or most of the other companies, raise pay and reward their workers for good work.

Bharati: But if you believe that market forces would determine fairness in wages, why even suggest a minimum wage?

Lim: Because there needs to be a fair starting point. Beyond that, we have to remember we are a market-oriented economy.

Bharati: Do you still stand by your suggestion of a moratorium for three years on further pay increases for those earning more than S$1 million per year?

Lim: Yes. There is this concern that if you leave market forces to handle top executive pay, you may, in the long run, end up in a spiralling effect on the economy, making ourselves uncompetitive. One leads to the other. If the top executive pay is so much, S$3 million, he finds it difficult not to pay his number 2, number 3, and there is that escalation tendency that might lead the economy in the long run, to go into the region of being uncompetitive, like in many developed countries. My first preoccupation is we must have the ability to compete in the global economy.

Bharati: Some might say that having a moratorium on pay increases would make us uncompetitive. Talent may not want to stay here.

Lim: I think it's a sensible moderate recommendation. I find that a few top employers (I don't think I would name them) even say that "my pay would stop at S$1 million and I don't want to have more". There were a few! If not, to address income inequality, taxes may have to go up. That will make us uncompetitive and make them not want to stay here.

Bharati: You said it should be voluntary, but really, do you think people would do this voluntarily?

Lim: You don't need to legislate this. The whole thing is based on the market mechanism. You only need moral suasion. If the NWC were to recommend it, and Government were to endorse it, it could work. We have a highly responsible and responsive society. It can work in Singapore, because we have a unique tripartite system.

Bharati: But again, you said earlier that NWC guidelines aren’t always implemented which is why you suggested a minimum wage.

Lim: Yes, but these are very small groups of people in the country. If Government says: "Have this moratorium", can you imagine any one of them would not follow? I doubt very much.

Bharati: You have a lot of faith in humanity.

Lim: I have a lot of faith in Singapore.

SHOULD NWC HAVE MORE TEETH?

Bharati: You have said that the NWC should indeed only issue guidelines rather than legislation, but you also bemoaned the fact that companies may not implement the guidelines and recommendations if they are not legislated.

Lim: Yes, because if you have a law it can be very rigid. Right from the word “go”, we did not believe in regulating wages by law because we are running a market-oriented economy. There must be a lot of flexibility in implementation. If companies are stubborn, and if workers find that their pay is so low relative to the pay of the other comparable companies, they would move there - provided we make sure there are job opportunities all the time. They would move. The companies would be forced to shut down because they won’t have good workers.

Bharati: You said minimum wage is a different kettle of fish. There must be a fair starting point. But beyond that, some might say why then even issue other wage guidelines, or suggest increases to the pay of low-income earners and a temporary freeze on the pay of high-income earners? Why not trust that market forces will determine salaries for both low- and high-income workers? You seem to believe in the effectiveness of that.

Lim: It’s again about the foundation. Firms in the public sector and in unionised companies in the private sector will follow the guidelines. Moral suasion may not always work that well with other firms in the private sector. But we have to have a balance between recommending measures and allowing the command economy to work.

Bharati: You are a proponent of maximum employment even if it means lower pay. During one recession, you suggested employers’ CPF contribution rate for older workers be decreased so that jobs would not be lost.

Lim: Yes, that is to ensure we continue to have maximum employment, full employment, to make sure we remain a very competitive economy.

Bharati: While we have seen a partial restoration of CPF cuts, some wonder if there’ll ever be a full restoration, especially for older workers who will need their funds for medical care and for retirement.

Lim: Yes, that is why at one point, I also called for a restoration. This is something that needs to be calibrated every few years. After all, we are in a command economy and to ensure employment, if during a recession, we need to reduce CPF contributions to increase workers’ chances of employment, to prevent them from losing their jobs, it has to be done. But we also need to restore the cuts in better economic times.

DO WE NEED REDUNDANCY INSURANCE?

Bharati: Lately, we have been seeing rising redundancies and some have suggested redundancy insurance. What do you think of that?

Lim: I don't think so. I am not very sure whether they should pay for insurance policies to take care of redundancies. But we have this system, which other countries may not have, which is a flexible wage system. It's flexible in the sense that when the economy is doing well, when the companies are doing well, they can pay workers more. But when the whole world economy is doing badly, when we have recessionary pressures, the companies can cut their pay. The variable component can go down.

Bharati: Why are you against redundancy insurance?

Lim: I am not against redundancy insurance. I am against making it compulsory. I am not so sure that is a good concept.

Bharati: Why do you have misgivings about it at this stage?

Lim: My fear is what I see in the Western countries. I have been trying to fathom why is it that a lot of them have an unemployment rate of 10 per cent or above. I think it is the rigidity of the wage system, and the rigidity of the hiring and firing system. When you hire a worker in some of these countries, you cannot fire them. It’s extremely difficult to fire a worker. So they have become very, very cautious in hiring people. So they always employ part-time people. So in implementing anything, you have think about whether it would have an unintended effect.

We are human beings. We always try to go for a better system, but in our search for a better system, we have also to take precautions that we are not opting for a less superior system.

POLICY OPTIONS FOR TODAY'S SINGAPORE ECONOMY

Bharati: Earlier, we mentioned a book you wrote many years ago, Policy Options for the Singapore Economy. What might you include in a similar publication if you were looking at the country's economy today, considering that we are in a world where technology is taking over functions that humans performed previously and jobs are being lost and businesses affected?

Lim: It's a very interesting and insightful question. Capital taking over from labour has concerned the minds of thinkers for a long, long time. You create technological unemployment.

By the way, when we restructured the economy in 1979 to 1981, we tried to change the economy from a highly labour-intensive to a knowledge-intensive new economy, in a very, very short period of three years. And the method, the modus operandi, was substitution of capital for labour. That means we mechanised, computerised.

Bharati: It's not new.

Lim: Completely not new. We succeeded. The GDP was not affected. The employment level was not affected at that time. It's interesting to know.

Bharati: But considering we are at a very different stage in our development, surely that can’t happen today.

Lim: Today our GDP per capita income is very, very much higher. So today, in terms of the substitution of capital for labour, what has to be done, has been done. The room for that kind of substitution is much, much more limited, much more difficult to carry out that kind of restructuring in the circumstances of that time.

Bharati: So considering these limitations, what do you think the approach should be today?

Lim: We should still try to raise our productivity through the substitution of capital for labour. You can include digitisation and better organisation. These are the perennial concepts. They are there always. We will always try to have better organisation, better arrangements, and the production process and more substitution where it's necessary.

You would not get into trouble if there are more and more investments taking place. But if you have an inadequacy of investment, your unemployment level goes up. You get into trouble. You get into a high-level equilibrium trap very quickly. It's stuck there. You have to make sure that people, foreign companies still find Singapore a good place to invest.

Our own companies, Singaporeans too, would want to start new firms, new factories, new methods of productions and expand their own production process.