25 years after investing big in biomedical sector, Singapore has tasted some success but the big league remains elusive

As Singapore nurtures homegrown startups and pushes for commercial success in biomedical sector, experts say the next leap forward hinges on global partnerships, business-savvy talent and a bold pivot towards emerging frontiers.

Several experts said that Singapore has put in place a world-class infrastructure for the biomedical industry but needs investors and collaborators from the rest of the world to take notice if it wants to take the sector to the next level. (Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

One of the few oral treatments available in the world for bone marrow cancer is a drug called Vonjo, which was created by Singaporean biotechnology company S*Bio – but few people likely know this.

The drug, which received approval from the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022, is among the few commercial successes out of Singapore's biomedical industry, which, despite a quarter century of nurturing, has yet to achieve global hub status.

When Singapore first began planting the seeds for its biomedical industry in 2000, the hope was that this new sector would eventually grow into the fourth pillar of the economy.

Fast forward to today and this ambition has yet to be fulfilled. Few innovations from biomedical and biotech companies based here have been commercialised, failing to translate science into feasible businesses that would contribute to the economy.

The ones that have made it to market, such as Vonjo, are not very well-known, which adds to the problem.

At the same time, the employment prospects for biomedical science students still seem less bright than those of their peers from other courses.

Numbers from the 2024 Joint Autonomous Universities Graduate Employment Survey, which was published on Feb 24, showed that graduates from the sciences course cluster earned a median monthly average salary of S$4,125 within six months of completing their final exams, lower than the S$4,500 average pay across all courses.

The survey also showed that these science graduates have a full-time permanent employment rate of 72.3 per cent within six months of their final exams, below the average 79.5 per cent.

As Professor Chng Wee Joo said, Singapore's biomedical sector has a “size and branding” issue.

The vice-president of biomedical sciences research at the National University of Singapore (NUS) added: “We need to have greater visibility on the capabilities of our system and sell our value proposition of a very integrated system with strong foundational infrastructure to attract more people to come and work with us in clinical trials and translation."

Indeed, several experts who spoke to CNA TODAY said that Singapore has put in place a world-class infrastructure for the biomedical industry and has a lot to be proud of – but it needs investors and collaborators from the rest of the world to take notice if it wants to take the sector to the next level.

Mr Paul Scibetta, who leads Singapore-based health tech investment firm 22Health Ventures, said in his 30 years doing business here, it is “obvious” that it has “great technology, great talent, policy and funding infrastructure” that makes the country “the best place in Asia to specialise in healthcare startups”.

However, Singapore’s biomedical startups are inexperienced in business development and need mentoring on this front, he said.

Singapore lacks globally sophisticated venture capital businesses that are based here that can mentor these startups and drive research from the very early stages to gear it towards market demands, he said, which has led to the scarcity of commercial successes.

Still, the experts said it is far from a lost cause and 25 years is a very short time in biomedical science.

Prof Chng from NUS pointed out, for example, that translating research into drugs takes on average eight to 10 years.

“We are the new kids on the block and need time to build our visibility and reputation. Compared to Boston and Palo Alto, our history is a lot shorter. In parallel, we need to grow the talent pool. This is being actively addressed but it takes time.”

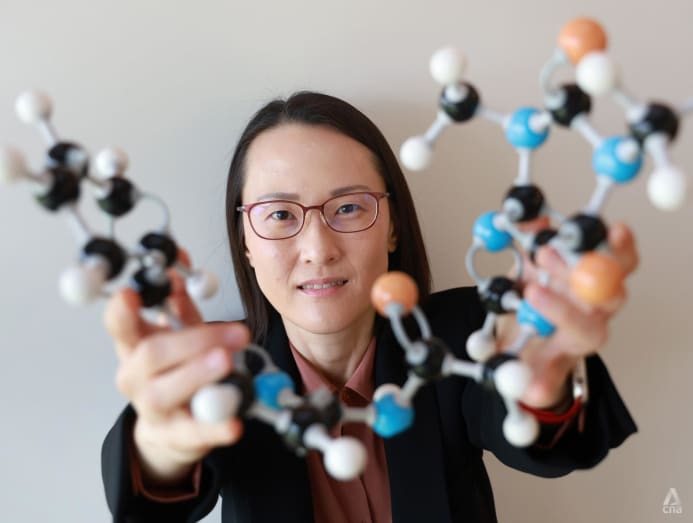

Dr Ang Hwee Ching, deputy chief executive officer of Singapore’s Experimental Drug Development Centre (EDDC), echoed this sentiment, saying that discovery and development is “really an effort that takes a village, takes an ecosystem, takes time, and we need to, over time, build up that expertise”.

SMALL BUT SIGNIFICANT SUCCESSES OVER TIME

The Biomedical Sciences Initiative, which the government launched in 2000, developed roots by growing research capabilities and attracting top global scientists here.

The initiative was steered by public sector agencies including the Economic Development Board (EDB), the former National Science and Technology Board, which is now the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (A*STAR), and JTC Corporation. It focused on raising human capital, intellectual capital and industrial capital for the nascent sector.

Research and development hub Biopolis emerged in 2003, sprouting an ecosystem of public and private companies to collaborate on projects. The government poured billions of dollars into the sector, creating new institutions and agencies, and biopharmaceutical companies bloomed.

Even as Singapore’s biomedical sector remains under the radar, it has chalked up notable successes in recent years.

One milestone was when EDDC earned a global licensing agreement in 2022, enabling German pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim to obtain exclusive worldwide rights to research, develop and commericalise products based on tumour-specific antibodies from A*STAR.

Dr Ang from EDDC said: “I think if you look at it, it was only possible because the government, more than a decade ago, recognised the importance of understanding gastric cancer, which is more prevalent in Asia.”

Separately, Japanese firm Chugai Pharmabody Research worked on a joint research project with A*STAR to create an anti-dengue virus antibody called AID351. In January this year, Chugai signed a deal with biopharmaceutical company GSK’s Global Health Unit, allowing the latter to evaluate potential funding to launch clinical studies of the treatment.

Arising from Singapore’s efforts, a handful of drugs developed here have been approved by the US FDA. Aside from Vonjo, there is an antibody treatment called Crovalimab, developed in Singapore by Chugai to target a rare and life-threatening blood disorder.

This gained US FDA approval last year, marking a key achievement for Singapore’s biologics innovation ecosystem.

Output from biomedical manufacturing and medical technology is growing from strength to strength, too. EDB said there are more than 60 biopharma manufacturing facilities here that produced S$18.7 billion worth of products in 2023, doubling the sector's output over the last two decades.

The medical technology sector has also tripled over the past decade, hiring more than 16,900 employees across more than 400 global and domestic enterprises, EDB said.

Separately, the number of Singapore-based biotech startups has risen from fewer than 10 in 2012 to 65 in 2023 and this number is expected to rise by more than 60 per cent between 2022 and 2032, EDB added.

SINGAPORE'S BIOMEDICAL INDUSTRY IN NUMBERS

-

The biomedical industry, comprising the biopharmaceutical and medtech sectors, accounted for 2.6 per cent of Singapore's gross domestic product in 2023

-

More than 80 of the world’s leading biomedical companies have their regional headquarters here

-

Almost S$38 billion worth of products were manufactured for the global market in 2023

-

The sector employs 26,481 people as of 2023

-

Since 2003, 712 patents related to drug discovery have been granted to A*STAR, of which 463 are active and in force

-

Between 1990 and 2018, the number of research scientists and engineers grew from about 4,000 to more than 36,000

PROGRESS IN COMMERCIALISATION

Mr Philip Yeo, former chairman of EDB who spearheaded Singapore's push to develop the biomedical industry, noted in a lecture on Mar 27 at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) that Singapore has been good at discovering new scientific innovations, but not as successful at bringing them to market.

That is not for want of trying and there has been some progress on this front.

He started Bio*One Capital in the early 2000s, a biomedical sciences venture capital firm dedicated to investing in homegrown companies and overseas ones that wanted to expand in Asia, though it has since ceased operations.

On top of that, to try to push the sector from focusing only on research towards delivering real outcomes, A*STAR created EDDC in 2019 to more effectively translate innovative biomedical discoveries in Singapore into new treatments. Its first commercial milestone was achieved with the licensing deal with Boehringer Ingelheim.

At the same time, a few Singaporean biotech startups have managed to attract venture capital funds, including Hummingbird Bioscience, which develops precision therapeutics for cancer and autoimmune diseases.

It is one of at least seven Singapore biotech companies that have managed to raise S$100 million or more since 2020.

Before 2020, only one Singaporean biotech company, TauRx Pharmaceuticals, had managed to attract more than S$100 million in a fundraising effort.

Dr Guy Heathers, a Singapore-based biotech entrepreneur and chief business officer of Albatroz Therapeutics, a biotech company developing tumour treatments, said: “When we have success stories, then we get more investors coming in and taking a look. It sort of feeds on itself. There’s nothing quite like success to create confidence and more success. And I think that’s key, to have more success to talk about.”

That is also why Mr Scibetta started 22Health Ventures, which helps to connect Singaporean startups with the biggest healthcare market in the world, the US, worth US$4.3 trillion a year, he said.

“I am using the US market as a commercialisation opportunity so that Singapore can prove it can produce globally competitive startups.”

Mr Scibetta said that his investment firm has a partnership with Enterprise Singapore. He also said the agency and EDB are some of the “most proactive, successful government partners any country has for a private business”.

Enterprise Singapore supports the country's growth as a hub for global trading and startups, and it is also the national standards and accreditation body.

Mr Scibetta added: “Mentoring of venture capital businesses is crucial and Enterprise Singapore is making sure that inexperienced founders get developed under many programmes in ways that give me confidence about Singapore’s startup ecosystem.”

EDB said that startups in the biotech, medtech and digital health space closed more than 30 deals in 2023, with a cumulative value of more than US$600 million.

These included funds raised from global investors, as well as licensing deals and development partnerships with leading biopharmaceutical and medtech multinational corporations.

For example, Johnson and Johnson JLABS supports early-stage companies with a base in Singapore to help accelerate their discoveries into innovative medicines, medical technologies and healthcare solutions.

FROM CAMPUS TO THE WORKING WORLD

Another bugbear that Singapore's biomedical industry has had to deal with is the lack of good jobs for Singapore students, a problem that seems to be persisting based on the lacklustre figures reflected in the 2024 Joint Autonomous Universities Graduate Employment Survey.

In the early 2000s, when the first few cohorts of biomedical science students graduated, many found themselves ending up in junior research positions or manufacturing and sales jobs that did not require a life sciences degree, while some gave up on finding good jobs in the industry and found careers in other sectors.

In 2002, Mr Yeo famously told life science undergraduates that they would only be qualified to wash test tubes with a basic bachelor's degree, because researchers needed a PhD.

Ms Christine Wang, 43, was one of these students who did not have an ideal start when she graduated with a degree in cell and molecular biology from NUS back in 2004.

She recalled that her salary in her first full-time role was only S$1,760, which was much lower than what her peers with other degrees were earning in their first jobs.

Although she felt that there were jobs available back then, there were also too many students graduating from biomedical sciences, so the positions did not pay well.

“There was a lot of promise that biology or science would be the next big thing in Singapore, so our parents were super supportive. And I remember our cohort was the largest – we had to split into two so that everyone could take the required modules,” she said.

Over the years, though, the 43-year-old has since carved out a successful career for herself in the biomedical sector, being a business development manager at clinical research company Thermo Fisher Scientific.

“There are more opportunities as there are more biotech industries and large pharmaceutical companies here compared to 2000. The biomedical research scene has also developed with more public institutions doing biomedical research, along with more startups,” he added.

That being said, the experiences of more recent graduates still seem mixed. Ms Lee Hui Jie, 24, graduated in 2024 from NUS with a degree in life sciences.

She managed to land a job as a medical technologist at a cancer diagnostics laboratory less than two months after graduation. She said she was "lucky" because the company reached out to her after she applied and she had to attend just two interviews before clinching the job.

However, during her brief job search, she sensed that the market was “very saturated” because every job listing had more than 100 applicants within just a few hours of being published.

She also noticed that some of her coursemates failed to land a job even a year after graduation. Some of them decided to pursue careers in other fields such as becoming financial advisers.

In response to queries from CNA TODAY, EDB said, though, that employment in the biomedical sciences industry has grown by more than 64 per cent in the last decade.

It pointed out that the sciences course cluster in the graduate employment survey may not be representative of the employment profile of the biomedical sciences industry, because the sector hires graduates from across different disciplines as well, not just life sciences.

"The entry-level roles in the biomedical sciences industry, depending on the functions, could be filled by polytechnic and university graduates from a diversity of courses," it said.

"For example, biopharma manufacturing plants would hire from a variety of engineering and science diploma and degree courses."

It added that other factors may have contributed to lower full-time employment rates, such as graduates taking a gap year or choosing to further their studies instead of starting work immediately, so it is hard to verify if the numbers truly point to a poor hiring landscape in the industry.

Ms Wang from Thermo Fisher observed that what has not changed since the early 2000s is that better credentials – such as obtaining a PhD – matter, especially for research roles.

“After a couple of years, many bioscience graduates realise that it’s difficult to progress if you just have a bachelor’s degree. If you want to do research, you definitely need a PhD,” she said.

“Without that, the furthest you can go is to become a laboratory manager, and probably nobody will sponsor you in terms of funding as well.”

However, Prof Chng from NUS remarked that, as compared to the 2000s, there are now more students pursuing biomedical science PhDs who then go on to work in industry or help lead startups arising from their PhD work.

To develop Singapore's pipeline of biomedical science talent, EDB said that it works closely with companies and Singapore's institutes of higher education to equip the resident workforce with industry-relevant capabilities.

For instance, Republic Polytechnic launched a new Talent Advancement Programme this year in partnership with 16 biopharmaceutical companies, providing a 36-week internship for about 360 students.

EDB also supports the Industrial Postgraduate Programme that NUS and NTU offer, allowing university graduates to further their studies. Under this programme, the postgraduate students would spend half of their time working on a research project in their sponsor company.

The government has been supporting mid-career Singaporeans in their career transitions as well. The Workforce Advancement Federation has a career conversion programme that helps mid-career hires reskill and make a transition into the biopharmaceutical manufacturing industry.

THE NEXT CHALLENGE TO OVERCOME

Experts interviewed by CNA TODAY noted that Singapore needs more late-stage clinical development of drugs, and it needs to cultivate its business networks in order to mature as a biomedical hub, enabling the sector to play a bigger role in the economy.

Ms Selena Ling, chief economist at OCBC bank, said that as a contributor to Singapore’s gross development product growth, the biomedical cluster is still relatively modest compared to finance, technology and trade.

“The sector is also concentrated by a few global players. And while the research infrastructure and ecosystem could be first-world, commercialisation could still be improved. The constraints may be a small domestic market and long timelines," she added.

She suggested that there could be greater support for regional export strategies and regulatory harmony to open up new markets.

This is on top of deeper public-private partnerships to accelerate product translation and more targeted incentives to scale up manufacturing and conduct more late-stage clinical trials.

Dr Heathers from Albatroz Therapeutics agreed, saying that as a small island, Singapore needs to be more “outward-looking” and partner with venture capital firms overseas.

“I think the challenge is to really reach out to overseas investors, overseas companies, overseas markets, to sort of leverage the technology base that we have in Singapore.”

When he first came here in 2000, he noticed the country’s inexperience in the biotech business model. Singapore was not used to growing an industry driven by innovation and relying on intellectual properties back then, he said.

For many years, Dr Heathers added, Singapore had a hot real estate market that dominated investor interest and funds. Waiting for a decade to develop a drug that would generate investment returns did not seem as attractive in comparison.

What ended up happening was that early startups propelled by government funding mostly focused on scientific research, and then faded away.

Prof Chng agreed, saying that in comparison with other successful biomedical hubs in the world, Singapore has a lower concentration of innovation and investors, and that investors here seem to have a lower risk appetite than elsewhere.

“We therefore need to have the stamina to persist if we want to see real made-in-Singapore successes, especially in the space of drug development,” he added.

Mr Scibetta from 22Health Venture raised the example of a country that Singapore could do well to learn from: Israel, which is now considered a startup nation.

He said that Israel started in a similar position to Singapore, being a small nation with a highly educated workforce and leading academic institutions. For a time, it also struggled with growing successful startups.

“The inflexion point was when it created a government programme in 1993 called Yozma, which induced venture capital businesses to base themselves in Israel." Today, Yozma's funds form the foundations of the Israeli venture capital market.

The programme transformed the country's landscape of private equity investments, establishing 10 funds and pouring money into startups. This became the start of a professionally managed venture capital market there.

“Look at what happened with the investment by venture capital into startups, which correlates with the successful startups in Israel. I am advocating that Singapore do something similar,” Mr Scibetta said.

Mr Yeo said in his IPS lecture that Singapore's scientists themselves need to become more business-savvy as well.

“One of the challenges is how to get our scientists to be more entrepreneurial. As scientists, they are passionate about research discovery, but how do you bring it to the market? You also need to encourage them to think business-wise.”

He suggested that Singapore could learn from the University of California San Diego, where doctors and scientists do a part-time Executive Masters of Business Administration (MBA) for 21 months at the American university's Rady School of Management.

“Maybe we have to think along this way, maybe NUS and NTU have to think of how to re-educate our scientists. A bachelor's of business administration is useless. I’d rather have a guy with an MBA who is also a doctor or scientist,” he said.

Indeed, Dr Heathers observed that, in his experience, when a biomedical startup receives funding, 80 to 90 per cent of the money goes towards research, while the remainder goes into the business development side.

“It’s a big R, small D sort of thing. I think that’s because most people in the ecosystem, local investors and government people who are tasked with developing a biotech industry, don’t quite understand that you need a 50-50 balance, like in the US, which is the leading country for this,” he said.

This gap manifests in the form of startups starting off with great research, demonstrating potential, but then “literally freezing” because they do not have any business or product development funding, so everything stops there, he added.

Mr Scibetta emphasised that this is why Singapore needs more venture capital businesses that can mentor startups on the business side of things and think about commercialisation, sometimes even before the company exists.

He said: “Singapore needs globally sophisticated venture capital that is based here, that started in this market. When the markets go down, they protect the Singapore startups, not recoil back to Boston or whatever overseas market, stop investing in your company and cause it to go bankrupt.”

An example of a fiasco was when one of Singapore's most promising biotech companies, Tessa Therapeutics, abruptly dissolved in 2023 after a market downturn hampered efforts to secure more funding and find a buyer.

The company, which was developing treatment for cancer cells, raised more than S$200 million in funding and was primarily supported by US-based healthcare investor Polaris Partners before it shuttered.

HOW TO CARVE A NICHE

As Singapore looks ahead to the next phase of its biomedical sector development, it would also do well to focus on emerging areas where it could carve out a niche, experts said.

Singapore is already responding to global healthcare shifts by investing in data-driven research, Mr Yeo noted in his IPS lecture.

For instance, the National Precision Medicine Programme aims to capture the complete genome of 450,000 Singaporeans of different ethnic groups. This would be used to gain deep insights for future proactive and preventive treatment of patients.

Mr Yeo also said that Singapore could share its data with neighbouring ASEAN countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam and collaborate with them, or even consider doing clinical trials in those countries.

This might also attract their scientists to come to Singapore to work, acting as a bridge to these nations.

Singapore should also do more to foster collaborations between smaller companies that discover and develop compound drugs and big international pharmaceuticals that can then run clinical trials, manufacture and distribute these drugs at scale, Mr Yeo added.

Several biomedical institutions here are also investing in new modalities such as nucleic acid therapeutics and cell therapies, he noted, which could possibly emerge as niche areas for the country.

Prof Chng from NUS said that Singapore will continue to be strong in biomanufacturing – producing medicine developed by multinational companies such as Novartis and Sanofi that have operations here.

At the same time, though, the country should consider developing new frontiers in the industry.

“With our scale and size, we must always be looking at what we can uniquely contribute and what our competitive advantage is. In a way, I feel it is better for us to lead from the front than try to overtake from behind,” he added.

For example, Singapore should develop a cutting-edge approach for the regulatory approval of products, especially in cell and gene therapies created here.

This is so that Singapore does not always have to follow regulatory frameworks or conduct trials in the US and Europe, enabling it to become "a leader, rather than a follower".

All in all, these efforts culminate in creating products and medicines that make people’s lives better.

Prof Chng said: “As a clinician, what I really hope is that our biomedical sciences industry will eventually produce outcomes that will have a real impact on the practice of medicine, patients and humanity.

"The short-term output of publications, patents and startups are great, but it is the impact on the patients and health of the population that should be our purpose.”

Novartis’ Singapore country president Poh Hwee Tee agreed, saying that she finds her work purposeful, because she is part of the process of creating medicine that helps not just patients but also their families.

Her own mother was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2017 and she went through the journey of being a caregiver until her mother went into remission. She is grateful that her mother is still alive, thanks to scientific advancements.

She recalled conversations with people who had loved ones die from certain conditions, for which treatments became available only a few years later.“You wish that if that drug had been made available five years earlier, your loved one would have been alive. If the person got the drug, maybe he or she could have lived two or five years more.”

Ms Poh emphasised: “So why are we doing so much to manufacture and commercialise? I’m very aware of the impact we have on patients. It’s not just the economy. We often think about the financials, how we benefit, but the biggest benefit is the end-user."