Why are vending machines popping up all over Singapore?

Some businesses are turning to vending machines to cut costs and improve reach – and consumers are biting.

Singapore recorded S$116.8 million in vending machine sales in 2024. (Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

A fresh bouquet of flowers, a serving of durian and a pack of pimple patches have one thing in common.

In Singapore, you can get these items at any time of day – in the event of a looming anniversary, an insatiable craving or an acne breakout – courtesy of a vending machine.

Once seen as nothing more than an emergency pit stop for a cool drink on a sunny day, these machines have become a legitimate and increasingly sophisticated way of doing business across a variety of industries.

Take the success of the founded-in-Singapore orange juice brand iJooz, for example. While growth was somewhat slow in its initial years, the business has since expanded to around 1,500 machines around the island alone.

Its chief executive officer Bruce Zhang told CNA in January that his company was not a juice retailer but a technology company, powered by in-house software with data-crunching abilities as well as hardware that squeezes oranges to a perfect pulp.

Likewise, Aikit Pte Ltd – a company that provides cook-to-order meals through more than 90 of its InstaChef vending machines islandwide – sees itself less as a vending machine operator and more as an automated kitchen.

This is because the technology within its machines allows for various methods of cooking food upon receiving an order.

For instance, when making claypot rice, the machine is able to create a charred and crispy rice texture that is similar to what you would get from a traditional kitchen, Aikit's vice-president for business and operations Sky Goh said.

This is opposed to a more common machine that uses an internal microwave to heat pre-prepared dishes.

Food and beverages are not the only products where the use of vending machines is gaining traction here.

For instance, tastefully assembled roses and tulips have made their way out of the florist and into portable glass displays.

Mr Perry Peng, the founder of White Dew Flower, told CNA TODAY that all four of his vending machines in Singapore have built-in refrigerators set at 5°C that keep the flowers fresh for a week — though he replaces them every three days to make sure they are in top condition for sale.

The popularity of these vending machines as a new avenue for business is in line with changing consumer behaviour, with a stronger-than-ever emphasis on convenience.

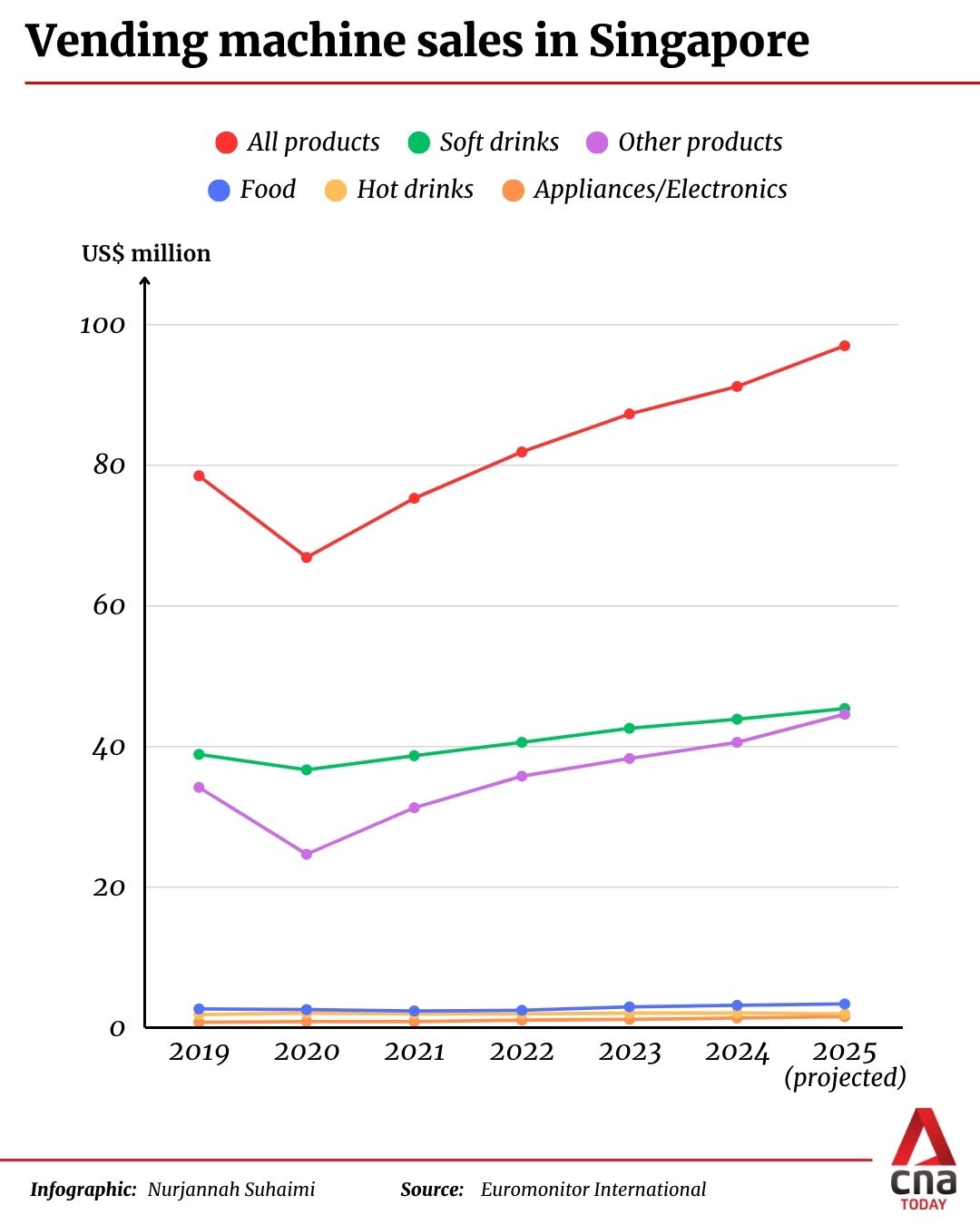

Statistics from data analytics firm Euromonitor International showed that vending machine sales in Singapore went up for four consecutive years from 2020 to 2024.

In 2019, sales stood at S$100.6 million (US$78.5 million), before the COVID-19 pandemic dragged down that figure to S$85.7 million in 2020.

Last year saw S$116.8 million in recorded vending machine sales and the figure is projected to reach S$124.3 million by end-2025.

What’s behind the increasing ubiquity of these automated machines and will this trend last?

LOWER COSTS, HIGHER GAINS

For brands such as Kaki Kaki, a Singapore durian seller that operates seven durian vending machines here, these machines offer a compelling alternative to traditional brick-and-mortar stalls because the price of rent is “significantly” more affordable.

“Singapore is quite a unique place, where even a clinic can pay S$52,000 in rent,” its representative told CNA TODAY. “I can’t sell S$52,000 worth of durians in a month.”

He was referring to the price that a healthcare firm bid for a shop space in a Tampines public housing estate earlier this month.

In contrast, the monthly cost of renting the far smaller space needed for a vending machine can range anywhere from S$300 to S$800 in shopping centres, and between S$600 and S$1,100 at bus and train stations, some operators said.

“At the end of the day, it’s about how we lower the cost and provide the same kind of quality and convenience,” the representative from Kaki Kaki said.

“The more we save, the more we are able to purchase better quality durians and pass on the savings to the consumer.”

Businesses that spoke to CNA TODAY declined to share specific figures, but most reported that demand for their vending machine products has been good.

Ms Magdalene Lim, country head for acne-care brand Dododots Singapore, said its vending machines that sell coloured hydrocolloid pimple patches typically turn a profit after three to six months.

“It provides our customers with a more convenient and instant way to get our products, while being able to save on costs involved like renovation, interior design and manpower,” she added.

OPENNESS OF CONSUMERS, LANDLORDS

At the same time, vending machine operators noted that landlords were increasingly open to leasing space to them – a trend perhaps exemplified by Kaki Kaki’s durian vending machine obtaining permission to operate at Tampines MRT Station.

Online users were initially intrigued, considering commuters are not allowed to take durians into carriages. Kaki Kaki said that its landlord, which is public transport operator SMRT, was very supportive of the idea.

Mr Justin Cai, an entrepreneur who tried his hand at running a fresh orange-juice vending machine back in 2018, said that setting up a vending machine operation was not that easy just a few years ago.

“As a small company, it was very difficult to get into malls and ask them for space. They felt we would be fighting (for business) against their existing fruit stalls and end up with a lose-lose situation.

“Even the malls that agreed would offer certain rental rates that are just not viable for a vending machine business,” he added.

Mr Vernon Tan, director of full-service vending operator Allied Vending, said shopping centres typically have two considerations when it comes to being receptive to vending machines: price and optics.

“If people are willing to pay more (for rent), I think they’re more open,” Mr Tan added.

“Space owners right now would also be more ready to think of where they can park machines and place them in aesthetically pleasing areas, whereas before, it was more of an afterthought.”

It also helps that customers such as 25-year-old public relations executive Brenda Chan are coming around to the idea of buying machine-dispensed products.

“For orange-juice machines, for example, I used to be slightly apprehensive because fruits can go bad quite easily,” Ms Chan said.

“But once I witnessed the worker changing out oranges and maintaining the machines, it made me trust that the products are kept in an ideal condition.”

GENERATING INTEREST FOR BRANDS AND CAUSES

Sometimes, the appeal of the vending-style model goes beyond just sales or an immediate impact on the bottom line.

Homegrown startup Ecoworks, for instance, has installed around 16 automated refill stations around Singapore.

Instead of dispensing items in single-use packaging, its machines dispense laundry detergent or dishwashing liquid alone, allowing customers to take used bottles to the machine to be filled.

Its founder Sean Lam said that its goal is to eliminate single-use plastic through what he termed “reverse vending”, where each transaction saves a bottle instead of dispensing one.

“Plenty of green initiatives here revolve around ‘recycling’, but the ‘reuse’ component is lacking. We are part of that solution. The bottle you have is still good enough for a second, third life.”

Mr Lam also said demand and interest in his machines have been strong, especially among public housing estates with Build-to-Order flats, home to many young families.

Apparel brand Ultifresh, which specialises in anti-odour and anti-bacterial sustainable clothing, also launched its first vending machine at AMK Hub in Ang Mo Kio two weeks ago.

Touting itself as a mission-driven company, its founder Frank Yap said the vending machine model was a “much faster” way than opening a storefront to achieve its objective of consumer education – wearing shirts more than once helps to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and save water.

Over in the fintech world, the finance application and neobank Revolut launched a debit card vending machine in 2024 at the National University of Singapore (NUS), where one may collect and activate the card on the spot.

Though it has recently relocated the machine to Galaxis retail and office complex in One-North, its novelty succeeded in drawing the NUS student population and ultimately, the use of its app, which aims to improve financial education in young adults.

In these cases, the machine itself served as a touchpoint, not just a transaction.

WILL THE TREND LAST?

The Singapore government has for several years been encouraging businesses to adopt automation and other productivity-enhancing technologies. And if rent and manpower costs continue to be a major hurdle for businesses setting up shop, industry players said the vending machine boom may well continue.

Euromonitor International's forecasts predicted total vending machine sales in Singapore to be on a consistent upward trajectory and that they would reach S$140.1 million in 2029.

However, operators warned against the misconception that starting and operating a vending machine is a bed of roses.

Despite the comparative amenability of landlords towards these machines today, Mr Tan of Allied Vending noted that finding a spot for them in the first place can be difficult.

“It’s not always easy to secure locations. Singapore land is very scarce … As more people get into the space, location fees may start going up and that eats into your business case.”

Mr Peng of White Dew Flower said this was the main challenge he faced in growing his business, where sales performance differs from location to location.

“There is a lack of available space for flower vending machines in shopping malls. Most malls already have a flower shop and those without one do not have designated spaces for vending machines.”

Ms Rohini Wahi, Asia-Pacific senior strategist at consumer trend forecasting firm WGSN, said vending machines had key advantages.

Ultimately, as affordability remains a priority for shoppers amid socioeconomic instability, these machines will bring retail offerings to time-poor and cost-conscious consumers that help them save time and money, she added.

In order to counter the oversaturation that comes with the growing number of vending machines offering similar products, brands need to go beyond convenience by embracing playful, creative designs and customising their offerings to each location in order to stay relevant, she proposed.

As long as operators continue innovating and engaging consumers meaningfully, the trend is set to endure – not as a novelty, but as a staple of modern retail.