Perfectionism can lead to inefficiency and strained relationships, say experts

Counsellors said that perfectionism makes people afraid of failure and prevents them from looking at the big picture, hindering personal growth.

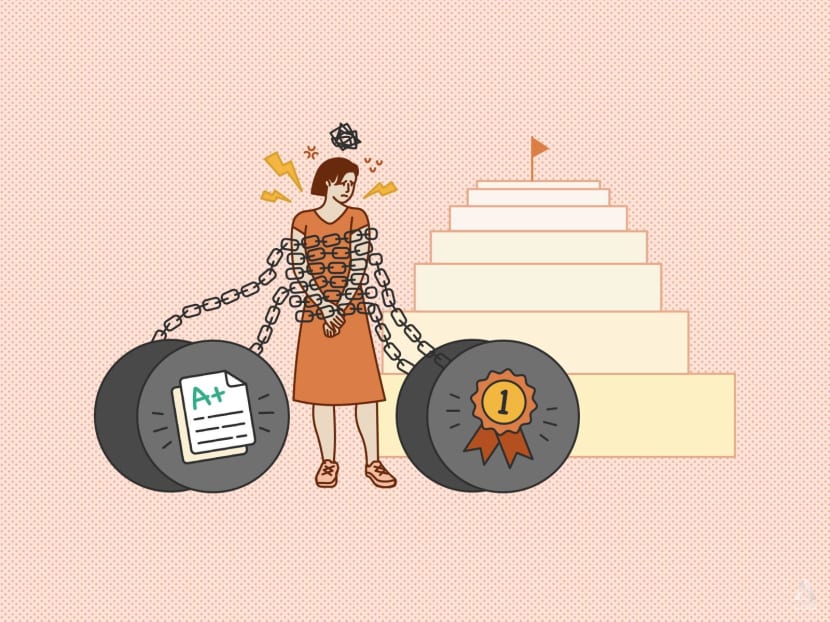

Perfectionism was a trait CNA TODAY journalist Eunice Sng struggled with during her school years. (Ilustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

During my schooling years, I struggled with perfectionism. For example, I was so obsessed with trying to get all the mathematics homework questions correct that I resorted to copying from friends or finding solutions online.

I hated the sight of red crosses and did not want my paper "stained" with corrections.

So rather than encouraging me to do my best, this perfectionism was an invisible chain that held me back from dealing with reality.

One time, I even sought out a counsellor because I scored a few Bs and wanted to repeat Secondary 2 for the chance to get straight As instead.

Eventually, the counsellor dissuaded me from doing that, but I still felt uncomfortable moving on to Secondary 3.

The tipping point came in junior college. As I was a student in the arts stream, many of my subjects required essays. But I was not always prepared to take the examinations as I did not have enough time to study.

So, during the examinations, I would leave entire papers blank instead of attempting to write down whatever little I remembered from lessons. I might have passed if I did the latter, but it felt so unnatural to write anything at all if I knew that I could not deliver a “perfect” essay.

This folly came at a cost – I failed almost every subject at the end of my first year and was promoted to the next academic year only by a hair’s breadth.

I knew I could not continue like this. I forced myself to pen down a few paragraphs even though I knew that the essays were not of spectacular quality. After that, I surprised myself by starting to score a few As and eventually did well for my A-Levels.

Looking back, I now see how self-destructive my perfectionism was. Instead of making progress to realise my true potential, it paralysed me into a state of inaction.

Mental health experts I interviewed helped me to better understand what drove this perfectionism in myself.

They told me that I was hardly alone and that the pressure-cooker environment in Singapore society is a breeding ground for perfectionism.

THE CULTURE WE LIVE IN

Singapore’s emphasis on academic excellence and meritocracy can make people feel like they are falling behind all the time, the experts said.

Mr Jasper Loy, counsellor from private practice The Healing Cove, said: “We live in a society that values perfection and makes it appear easily attainable, but perfectionism ignores the fact that we are human and prone to making mistakes.”

Ms Tong Hui Wen, a counsellor at mental health clinic Intellect, said that the constant comparison especially during family gatherings – whether over grades, rankings or career milestones – can make people feel like they are only as good as their last achievement.

“I’ve seen a lot of young adults who tie their entire self-worth to their academic or professional success, which can be incredibly damaging to their sense of unworthiness,” she said.

She added that in many families here, there is a strong emphasis on maintaining a positive reputation in order not to embarrass the family, which can lead to an immense fear of failure.

Ms Tong has worked with clients who felt great pressure to meet their parents’ expectations, whether it was getting into a top school or landing a prestigious job.

“This can create a cycle where perfectionism is passed down through generations, as parents who were once pressured themselves may unintentionally impose the same standards on their children,” she added.

In careers, Ms Tong observed that it could be an employee working late every night, unable to delegate tasks because they fear others would not meet their standards.

Perfectionism can even manifest itself in relationships, when people constantly seek approval or fear rejection if they are not the “perfect” partners or friends, she said.

STRIVING FOR EXCELLENCE VERSUS PERFECTIONISM

The mental health experts said that chasing high standards is not necessarily a bad thing, and can even be helpful for growth when managed in a healthy way.

But when the goal is to make everything perfect and apply this approach to every aspect of life, it becomes harmful because an individual may focus too much on getting all the details right, as was the case with my essays in junior college.

Ms Lilian Ong, a counsellor from private practice Wellness Journey, said that being focused on making everything perfect causes them to lose sight of the big picture, become less efficient, tire themselves out and strain relationships when they expect others to follow their high expectations as well.

Ms Tong from Intellect cited an example of a client she worked with who spent hours rewriting emails because they had to be “just right”. This left the person exhausted and unable to focus on more important tasks which they then beat themselves up over, creating a vicious circle of self-flagellation.

Ms Tong also used the analogy of climbing a mountain. She explained that those who strive for excellence enjoy the journey, celebrate small wins, and adjust their path as needed when they encounter obstacles.

Perfectionism, on the other hand, is like scaling the same mountain but constantly looking down and being terrified of slipping, she said.

“The key difference lies in mindset. Pushing for excellence is driven by growth and curiosity, while perfectionism is fuelled by fear and self-criticism.

"Perfectionists often think in black-and-white terms – something is either perfect or a failure – hence, they often struggle to accept the shades of grey in life.”

Perfectionism also keeps people within a “safe zone” where failure is unlikely. Ms Tong once worked with a talented artist who refused to showcase her work because she felt it was not good enough. This fear of imperfection stifles creativity and personal growth.

Ms Ong from Wellness Journey said that the perfectionist wants to be absolutely sure of the outcome before making a decision or embarking on something new. So they may take a long time to consider multiple factors or decide they cannot risk the uncertainty.

This might mean missing opportunities for new experiences.

“When we see people procrastinating, we may think it is due to laziness or lack of motivation, but it could also be due to perfectionism and the fear of failure (which means) that they decide it is better not to try," Ms Ong added.

Such people may have the mindset that “if I can’t do it perfectly, I might as well not do it”, she added.

Another reason perfectionism may lead to inaction is that because it takes so much effort to get things perfect, it becomes so daunting that the person just decides to give up, she said.

HOW TO OVERCOME PERFECTIONISM

Ms Fion Liew, a lead counsellor from Awaken Counselling Centre, said that the first step towards unlearning perfectionism is to recognise the toll that it takes on one’s well-being. This provides the motivation needed to explore healthier patterns.

But changing takes time and intentional effort. To begin altering how someone perceives their self-worth, Ms Liew said they can try to adopt a “good enough” philosophy.

“Learn to feel comfortable with outcomes that are sufficient, which can save time and reduce unnecessary stress,” she said.

Ms Ong suggested that perfectionists can identify some “lower stakes” situations to start practising letting go of their usual standards.

For instance, they can allow themselves to wear mismatched socks, shirts with creases not ironed out, send out a text message without correcting grammatical mistakes or leave the dirty dishes undone for a day.

“It will be uncomfortable at first, but you also gradually realise nothing disastrous happens when things are not perfect, and you witness how liberating it is to stop chasing perfection,” said Ms Ong.

She also advised people to change the words they use in their self-talk.

Instead of thinking in absolute terms such as “it must”, “I should” or “they have to”, perfectionists can instead practise phrases such as “it would be nice if”, “I would prefer”, or “it would be good to”, creating more openness to different possibilities.

Ms Liew added that they can also shift their mindset from “I can’t do this” to “I can’t do this yet”. This simple reframing emphasises learning and growth rather than perceived failure.

She also encouraged perfectionists to focus on the process, not just the outcome. “Pay attention to the effort and intent behind your actions. For example, when writing an email, concentrate on clear communication rather than striving for perfection in phrasing.”

Overall, the counsellors agreed that embracing imperfection fosters resilience and psychological flexibility.

Ms Liew said that this approach empowers individuals to approach setbacks with grace, learn from their experiences and persevere through difficulties with a sense of purpose.

Ms Ong advised: “Instead of wasting energy wishing that things were perfect, we can channel our resources to deal with the challenges more effectively.”

However, external forces also play a huge role. For instance, a person's social circle, educational environment and societal norms significantly shape how they view themselves and their work Ms Tong said.

Ms Ong encouraged parents and educators to tell adolescents to simply “give their best”, instead of expecting them to “be the best”. This teaches them to value the process and effort rather than perceiving themselves as not good enough if they fall short of expected outcomes.

Mr Loy suggested that parents may create opportunities for their children to engage in challenging activities where perfection is not possible, such as trying a new sport of tackling complex puzzles.

“The goal is to help them develop comfort with the discomfort of not being immediately good at something,” he said.

After hearing all of these tips, it struck me how I used to equate my self-worth with validation from those around me. I thought that if I pursued flawlessness, I would be seen as successful by my friends, parents and teachers.

But the toxic fixation on inadequacies left me feeling stuck and miserable all the time.

My resilience and determination to improve after every mistake mean more to me now than how many marks I scored in an examination a decade ago.

I am imperfect. And these imperfections are precisely what make me human.