Before actors undress for raunchy scenes, this Singapore-based intimacy coordinator sets the rules

Under the watchful eye of Ms Rayann Condy, steamy scenes don't get messy. As the only certified intimacy coordinator from Singapore, she's trained to handle on-set intimacy the right way.

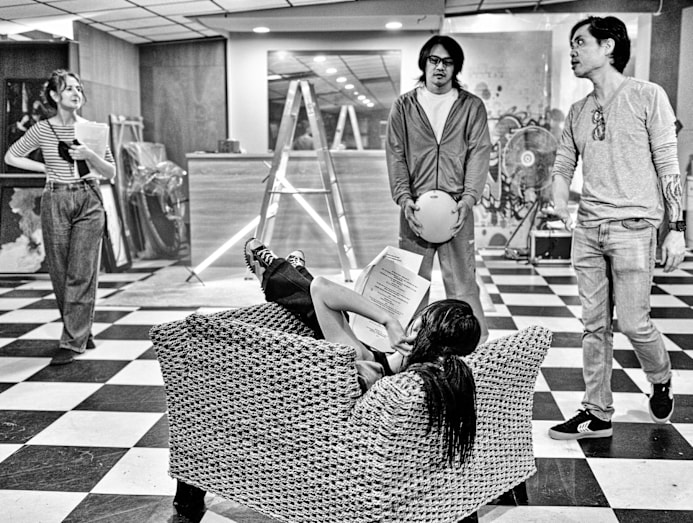

Ms Rayann Condy, a pioneering intimacy coordinator in Singapore, at The Singapore Airlines Theatre in LASALLE College of the Arts on Nov 11, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Alyssa Tan)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Most of us would probably rack up numerous human resources violations if we got into a passionate makeout session with a colleague in full view of the whole office.

Not actors, though – that would be a regular Tuesday on set.

Still, I imagine the ubiquity of intimate scenes doesn't erase the awkwardness of swapping spit with a co-worker you may have just met. Nor does it defuse the minefield of developing a shared understanding of what those instructions on intimacy actually mean.

Overlaid with the messiness of human interaction, seemingly straightforward lines can be anything but.

Take the instruction: "They kiss", for example.

A director may picture "the male actor twirling the female around and tumbling into bed", while to the actors involved, it could just mean "a peck on the cheek".

Some production sets, therefore, hire a professional to get everyone on the same page – someone trained to make those moments safe and clear for all involved.

In Singapore, that responsibility often falls to 45-year-old theatre veteran Rayann Condy.

She moved here from Australia in 2005 to pursue a bachelor of arts with honours in acting at LASALLE College of the Arts, as part of the programme's inaugural batch.

Wanting to live somewhere new, she weighed her options: London or Singapore. Though she'd spent plenty of time in the United Kingdom – her father is British – she'd never visited Singapore. But the city won her over with its sunny weather, and her alma mater, with its reputation.

Now a Singapore permanent resident, Ms Condy is the only person based here to be certified by Intimacy Directors and Coordinators, the leading global body for training and accrediting intimacy professionals.

The group is recognised by SAG-AFTRA, the United States labour union representing a range of media professionals.

There are five phases to becoming a certified intimacy professional, including three self-paced online modules, an in-person workshop and one-on-one mentorship.

Those certified also earn lifetime access to the like-minded community.

An intimacy coordinator and intimacy director since she received her certification in 2023, Ms Condy helps film, television and theatre production sets approach sensitive scenes – from romantic moments to nudity or simulated sex – with professionalism and care.

The term "intimacy coordinator" is used for screen and "intimacy director" for stage, though most people use them interchangeably.

But for Ms Condy, the title carries more than just professional weight. If she'd been granted the same safe space that she now creates for others, she believes certain experiences might have played out very differently.

"NOT LIBERAL ENOUGH"

As a young freelance actor in her early 20s, Ms Condy would convince herself she was "not being liberal enough" whenever she felt uneasy performing intimate scenes.

Back then, intimacy professionals didn't exist as a formal role.

It wasn't until the #MeToo movement went viral in 2017 that the industry began re-examining how safety, consent and personal boundaries were handled in scenes involving physical intimacy, nudity or simulated sex.

Now married without children, her memories of one stage production in Australia still resonate.

The play was centred on couples and, unsurprisingly, included moments of "what one might call pedestrian or low-key intimacy" – scenes of kissing and "flirtatious disrobing" involving partial nudity.

These acts required both sensitivity and care, yet for most of rehearsals the director gave only verbal instructions until the scenes were first run.

"This is where the kiss will happen. This is where you'll do this huge make-out. It'll be so sexy and you'll take your shirt off," she recalled him saying.

When she and her male co-star eventually approached the scene in the final week of rehearsals, they were simply told to get on with it – and so they did.

Some two decades later, Ms Condy still remembers it "being very awkward" and that the other actor used his tongue during the scene which made her "very uncomfortable", she said.

"I was also supposed to appear naked from behind … while facing upstage towards my scene partner," she added. "But there had been no conversation about (my) coverage from the front. I struggled to hold my top up in front, while taking it down at the back."

In the end, she faced her fellow actor topless.

The idea that an actor is allowed to have boundaries wasn’t part of my vocabulary.

But the moment that stayed with her more vividly happened backstage, when she overheard him and another male actor bantering about their female co-stars.

"(My partner) said: 'Well, I get actual breasts'," she recalled of his blunt description of their scene together. "I was mortified. I was so embarrassed that he would talk about that and say that so flippantly."

The other actor then joked that he felt cheated because his scene partner wore a stick-on bra, she added.

Up till that point, Ms Condy never realised that protecting her modesty was an option. The other actress, who was more seasoned than her, hadn't thought to share that they didn't need to be naked, either.

Although Ms Condy was taken aback, she later reasoned that it shouldn't have been another actress' job to inform her.

"Nobody had had that conversation because the ideology of actor training was very much: 'You must say yes to everything, you must give your body to the craft.' The idea that an actor is allowed to have boundaries wasn't part of my vocabulary."

BEING A SAFE SPACE FOR OTHERS

Meeting Ms Condy for the first time in late October, it was hard to believe she ever felt powerless.

Throughout our hour-long conversation at Dewgather cafe in The Star Vista, it was clear that she is incredibly assured in her role – but it wasn't just her measured speech or clear-eyed way of addressing the scepticism surrounding intimacy work.

She's also self-possessed in a way that puts others at ease. Our conversation felt less like an interview, and more like a catch-up with an old friend.

Admittedly, this disposition could be because she's also been a lecturer at LASALLE since 2010, a couple of years after her own graduation.

She teaches in the bachelor of arts in acting, bachelor of arts in musical theatre and diploma in performance programmes.

Her responsibilities include an acting for camera module that incorporates intimacy skills, giving students the "vocabulary" to start conversations with their scene partners.

She also covers viewpoints, a module on improvisation techniques that has "historically been kind of a physical free-for-all", she said. So she's begun to introduce "scaffolding": Safe words and check-ins around consent and comfort.

After all, should students eventually pursue an acting career, they would realise not every production has an intimacy professional.

Fifteen years in the classroom has reinforced to her the importance of helping newcomers feel safe enough to speak up, be it about their fears or the pressure to appear fine with intimacy while anxiety quietly builds.

From the get-go, she seeks to understand both the director's vision and actors' boundaries, after first combing through the script herself.

To fine-tune the details of a kissing scene, she may ask the director: Is it meant to be a steamy make-out session? Is the female actor's back facing the audience? Should there be a sense that she's naked?

Actors, meanwhile, are encouraged to be just as precise about their own limits.

Some may agree to lip-to-lip kissing but draw the line at French kissing, while others may be fine baring their back, if they can cover their breasts with nipple tape, a stick-on bra or a crop top.

What's key is these conversations with actors happen privately and "outside the power dynamic of worrying about pleasing the director and producer, and even pressure from co-actors", she emphasised.

She remains empathetic to actors, even though she's stopped acting in favour of behind-the-scenes work. Her last role – as a minor character in a friend's short film – was in 2015.

She had realised around two years into her time in LASALLE as a student that the spotlight wasn't for her in the long term.

Moreover, she volunteers with the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE), facilitating its sexual assault first responder training.

The experience has made her more alert to how power plays out on set.

"Harm from good industry players is sometimes more prevalent," she said.

"With a director you love and respect, (the desire to) do the right thing and give them what they want is probably higher than with somebody you clearly don't like and probably don't want to work with again."

She recalled a male actor who winced at the request to shave his chest hair off to play a vain character and yet obliged. Thankfully, she caught his discomfort in time and raised it with the director, who readily agreed to find another solution.

As such, she watches closely for signs that an actor isn't being completely candid.

With a kissing scene, they may only disclose that this is their first stage or screen kiss, leaving her to sense their "apprehensive body language".

"I might – if it's appropriate and without breaching their confidentiality – mention to the director that I have a sense this (scene) is on the border of this actor's boundaries and we might need to be ready to change plans," she said.

"(Because) if I'm clear about what the director wants to achieve in storytelling and what they want the audience to feel, there are a hundred different ways to get to that point."

LEAVING ROOM FOR CHANGE

Occasionally, however, an actor's boundaries only become clear during "blocking" – the choreography of movements and positions in rehearsal.

For instance, they'll work out which parts of their co-star’s body they're comfortable touching. Some are fine with hands on their face but not the nape of their neck. They'll also decide which way to tilt their head during a kiss and how long that kiss should last.

And this shift from talking about the act to actually making physical contact is "very slow and gradual" by design, Ms Condy said.

"There’s a lot of time built into this for the actor to go, 'Oh, in my mind, it was okay when you put your hands here, but now in real life, it's not okay anymore.'

"The process should allow us to catch (this discomfort) before somebody is pushed into panic or freeze mode or a damaging bodily response."

Trickier still is that consent can change at any time and she added that "that is okay".

She was once brought onto a set in the fourth week of filming, when tensions between an actor and the director were already running high and what the actor initially agreed to no longer held.

The change wasn't a reflection of the actor’s boundaries "in a neutral state", but about a loss of trust, she realised. And it could've been avoided with an intimacy professional to mediate before things soured.

In an ideal world, Ms Condy pointed out, an intimacy coordinator would be brought in early, rather than after the first table read or when problems have already surfaced.

While she gives guidance for scenes involving nudity or simulated sex, she is also hired to oversee other intimate scenes that are just as crucial, though often overlooked.

There are also scenes where a character bathes another or soldiers press on a comrade's wounds in battle – and all involve "incredibly intimate contact".

One example of "unconventional" intimacy is a 2024 short film A Witch Trial, which she worked on for Biome Entertainment in Singapore.

While there wasn't any physical intimacy, it involved implied psychological violence in its language and imagery.

"That was potentially quite traumatic acting," she said, adding that there are more productions which are beginning to recognise that intimacy encompasses more than just physical sexual contact.

TACKLING MISCONCEPTIONS

To date, she has worked on more than 20 screen and stage productions in Singapore and across Southeast Asia – from Wild Rice’s recently-concluded The Serangoon Gardens Techno Party Of 1993 to Shakespeare In The Park: Macbeth by Singapore Repertory Theatre in April.

But despite growing awareness of intimacy work, she still finds herself reassuring people that she's not there to "usurp a director's relationship with an actor".

That is perhaps one of the biggest misconceptions about her still-new profession.

It doesn't help that some major Hollywood actors, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Anniston and Sean Bean, have suggested that intimacy coordinators stifle creativity.

Earlier this month, Jennifer Lawrence became the latest celebrity to echo that sentiment. While promoting her movie Die My Love on a podcast, she revealed that she declined the help because she felt "safe" with her co-star Robert Pattinson.

Ms Condy, of course, doesn't dispute that trust among everyone on set is key.

But her job, if she does it right at least, should prove that safety and creative freedom aren't mutually exclusive.

I'm not an actor myself, but I do see how the boundaries of safety can allow for greater creativity in collaborative spaces. When everyone feels secure, they can relax – not stay on guard, constantly fearful of crossing someone's lines.

In fact, a lack of clear guidelines can even prove counterproductive. Ms Condy explained: "The storytelling gets lost when the actors are busy thinking, 'God, what do I do?', rather than about the story."

Nowhere was this risk more evident in recent memory than on the set of It Ends With Us. The 2024 film reportedly lacked an intimacy coordinator – a decision that came under fire after Blake Lively accused co-star and director Justin Baldoni of sexual harassment.

Yet, such moments only reaffirm why Ms Condy's work matters in the first place, as do the conversations she insists on having.

"Ultimately, one of the things that people don't realise with hiring an intimacy or care professional is that it actually sets the tone for the whole production," she said.

"It says to the entire team: We care. Safety is important to us, because boundaries are important to us. We're creating a culture of respect."