The rise of Jackson Wang and China’s quest for a global pop idol

The patriotic star from the K-pop group Got7 embodies a Chinese push for success in the west, but can C-pop emulate the soft power of K-pop? The Financial Times' Ludovic Hunter-Tilney takes a look.

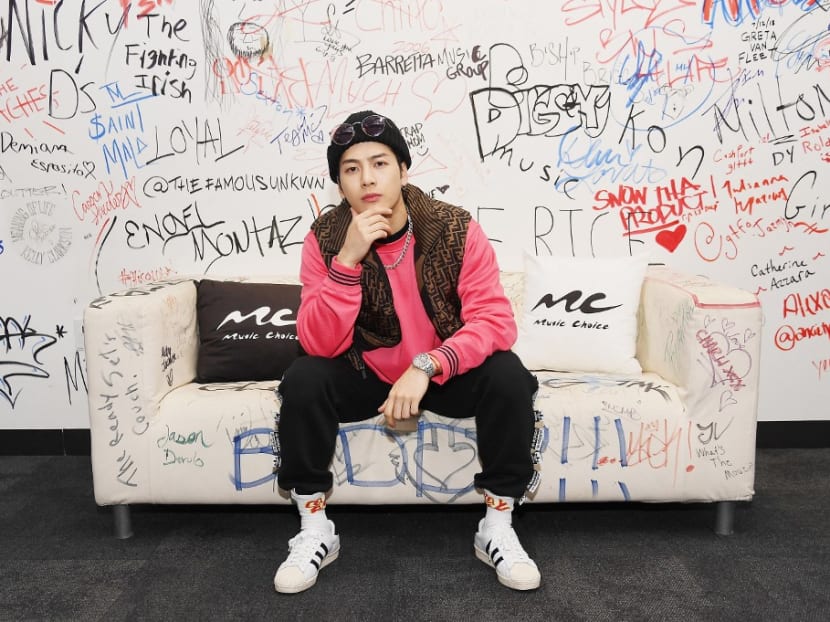

Jackson Wang in New York City in 2019. (Photo: AFP/Nicholas Hunt/Getty Images)

Can a Chinese pop star make it big in the west? Rising tensions between China and western nations suggest not. But the thousands of fans who have flocked to gigs by Jackson Wang in London and Paris this month indicate otherwise.

Wang is a singer from Hong Kong who is currently on a world tour. Last year his album Magic Man charted at No 15 in the US charts and he became the first solo Chinese act to play Coachella in California, one of the world’s biggest music festivals.

“This is the moment of history, this is Magic Man – this is Jackson Wang from China,” he grandly announced from the stage. “#JacksonWangCoachella” promptly trended on Twitter, the modern version of history’s first draft.

Due back at Coachella in April for this year’s line-up, he is actively courting western success. The slickly enjoyable pop-rock songs on Magic Man have a Harry Styles-ish quality. They are sung in English, in which Wang is fluent. He was born in 1994, when Hong Kong was a British colony. But he now projects an uncompromisingly patriotic Chinese identity. In 2019, he was criticised in Hong Kong for his pro-Beijing stance during mass protests in the city against mainland Chinese control.

During his London gig at Hammersmith Apollo last week, he delivered a diatribe about “bullshit” coverage of “my home country” in the western media. “If you travel to China one time, you’ll feel like, ‘damn, this a dope place',” the pumped-up singer declared. He was answered by a volley of screams from fans.

SOFT POWER AND NATIONAL BRANDING

My request to interview him for this small corner of the western media was refused: Wang was apparently doing no press in London or Paris. His rising profile runs in tandem with China’s increasingly prominent role in global popular culture. TikTok is the most famous example – the attention-devouring social media platform is owned by Beijing group ByteDance.

Another Chinese tech giant, Tencent, is focusing resources on selling video games internationally. Last year it embarked on a strategy to buy up western gaming companies, such as the Danish makers of mobile hit Subway Surfers.

Political scientists call this “soft power”. South Korea is held up as the quintessential modern case through its “Korean wave”, or hallyu, of state-supported creative industries. At its vanguard is K-pop, which over the past decade has become a major force worldwide with the emergence of chart supremos such as BTS and Blackpink. They are at the summit of the mountain that Wang is climbing.

“Soft power has always been an important agenda in China’s national branding,” said Anthony YH Fung, professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “But pop music is one of the areas that has not proved so successful.”

In 2011, the Chinese government partnered with a Shanghai entertainment company to launch the Earth’s Music project, a 10-year plan to create a global pop star. A singer called Ruhan Jia was recruited for the post in 2014. Classically trained – she appeared in the UK world premiere of Damon Albarn’s opera Monkey: Journey To The West in 2007 – Ruhan underwent a crash course in western pop, studiously listening to Michael Jackson and Queen. Not altogether unsurprisingly, the campaign to conquer the world’s charts with a People’s Republic-sponsored star flopped.

“That was somewhat of a borderline case,” Fung said. He pointed out that the country’s size and language barriers have impeded China from developing exportable pop music. “Chinese artists are usually only Chinese-speaking when they develop within China,” he said. “And the Chinese market is huge. If an artist becomes popular, they can make a lot of money. A concert tour of 10 Chinese cities is probably as big as if they go around the world.”

C-POP, CANTOPOP, MANDOPOP…

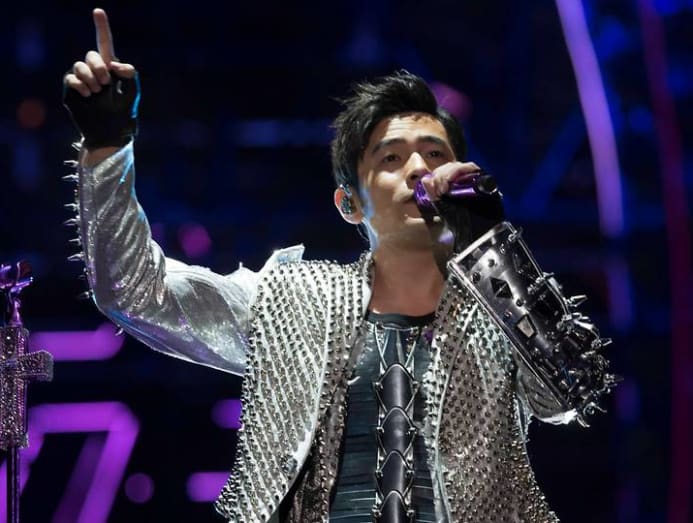

C-pop is the umbrella term for all types of Chinese popular music. It encompasses numerous genres, including Cantopop and Mandopop. The former is sung in Cantonese and originated in Hong Kong. Its popularity has faded since the 1990s, although there are signs of a resurgence. Meanwhile, Mandopop uses China’s official language, Mandarin Chinese, which is also spoken in Taiwan. One of China’s best-selling stars is the Taiwanese Mandopop singer Jay Chou.

“When Hong Kong singers want to be successful in the China market, they have to change language,” Fung said. “That’s why Hong Kong remains relatively different and autonomous from the main Chinese market. Taiwanese artists can move to China more easily. They don’t have the language barrier. But now there are political problems. If they want to do concerts and sell albums in China, they have to declare their loyalty.”

Cantopop’s decline in importance parallels Hong Kong’s dethronement by Seoul as the region’s leading entertainment centre. Jackson Wang epitomises the shift. His background lies in neither Cantopop nor Mandopop. In 2011, aged 17, he moved from Hong Kong to Seoul to train as a K-pop artiste. Following an apprenticeship in Korean reality television programmes and talent shows, he joined the boy band Got7 in 2014.

Got7’s other members are US-Taiwanese and Thai as well as South Korean. The multinational, multilingual mix is typical of K-pop’s recruitment policy for its “idols”, as stars are known. The aim is to appeal to audiences throughout Asia and its diaspora.

“At least 66 artists of Chinese descent have become K-pop idols,” said Sun Meicheng of Beijing Language and Culture University, a specialist in the close but prickly association between K-pop and China. She traces the first Chinese idol to a Mandopop singer called Han Geng who joined the Korean boy band Super Junior in 2005.

K-POP AND CHINA

The world’s most populous nation is a critical market for K-pop, despite episodes of friction. In 2016, the Chinese state banned Korean acts from touring in retaliation for South Korea’s installation of a US missile defence system. Chinese K-pop performers were exempted from the prohibition. So was Hong Kong, which was allowed to continue hosting Korean concerts. K-pop is too big to outlaw entirely in China.

“The popularity of K-pop in China has remained similar since the so-called ‘Korean ban’,” Sun says. “K-pop albums have been released on Chinese music-streaming platforms and local small-scale K-pop-related events have been held by fans. However, no large-scale K-pop concerts have been staged in China since 2016.”

Other Chinese acts hoping to match Wang’s western success share his K-pop background, such as Lexie Liu, a singer and rapper who partly performs in English and is signed to American record label 88rising. Another is Ningning, a member of the chart-topping girl group Aespa, who has released anglophone solo songs. They are products of the South Korean music industry.

Meanwhile, Chinese entertainment companies have their own rosters of boy bands, girl groups, rappers and solo singers. K-pop’s promotional methods and production values are mimicked – but its usefulness as a model only goes so far.

“Say, for example, a Korean artist tries to become more androgynous, with make-up – these kinds of things are not acceptable to the Chinese authorities,” Fung said. (In 2021, an official edict fulminated against “sissy idols” and “effeminate men”.)

“Nowadays, Chinese entertainment companies don’t want to copy too much, otherwise they might be banned by the authorities. They try to keep a certain distance from Korean pop, even though they know that this is among the most popular styles in the world.”

K-pop’s Chinese idols have not escaped the mounting ill-feeling. Last year, Wang Yiren of girl group Everglow was abused online for using Chinese etiquette to greet fans in Seoul rather than kneeling like her Korean bandmates. (Kneeling is considered subservient in China.) “Go back to China,” she was told by nationalist Korean netizens.

Wang’s adamant expression of pride in China at his London gig was like a flag planted on new territory. But it also disguised the not-so-straightforwardly Chinese aspects of his success. “Only Chinese people trained outside the mainland could represent this kind of Chinese-ness to sell to the rest of the world,” Fung said. “If they were trained within China, they could not have this style of Korean performance aesthetics. They simply don’t have that personality.”

Jackson Wang is a pioneering Chinese pop star. But despite his patriotic protestations, he owes more to South Korea for his western success than to China. That has been his gateway to the west, and so it is likely to prove for any successors who follow in his sharply choreographed footsteps.

Ludovic Hunter-Tilney © 2023 The Financial Times