Domestic violence in childhood: What drove 2 Singaporeans, a businesswoman and a pastoral counsellor, to repair mental health

- In the third of a four-part series on childhood trauma and adverse experiences — in conjunction with World Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Day on April 23 — TODAY speaks to two women who were victims of domestic violence during their growing-up years and how they sought healing as adults

- The first part is on how abuse, parents' divorce and living with mentally unwell persons can affect a child's lifelong health and relationships

- The second addresses what health and social work professionals do to help these children

- The fourth examines how to process past hurts and practise forgiveness when you have had a difficult or traumatic childhood

- Please be advised that the articles delve into topics and accounts of trauma and abuse that may be triggering to the reader

Growing up, home was not a safe place for Singaporeans Sharon Khoo and Nanny Eliana. The women separately recalled a time when they lived in a state of tension, anxiety, stress and uncertainty, where personal security was almost non-existent in the midst of domestic upheavals.

What does a child do when the very adults meant to protect and nurture them become the source of their nightmares?

For Ms Eliana, 45, and Mrs Khoo, 39, they carried the weight of their difficult growing-up years into adulthood.

Both women later sought professional help to equip them with the skills to rebuild their mental health that had suffered due to domestic violence.

In conversations with TODAY, they bravely told of their adverse childhood experiences and how those early years shaped the course of their adult lives.

The term “adverse childhood experience” refers to a potentially traumatic situation or event that a person may face or witness while growing up.

FROM 'BEST FRIEND' TO ABUSER

The first seven years of Mrs Sharon Khoo’s childhood was filled with good memories.

She reminisced about the road trips to Malaysia with her parents, the joy of learning to ride a bicycle and playing hopscotch with her father.

“Back then, my father was like my best friend. He was always the fun guy,” she said.

Everything changed when she turned eight.

It felt like I was living with a terrorist, like he wasn’t my dad anymore... Home was like a hell hole; I was scared that I was going to die in there.

Her father could not control his emotions and the fits of anger soon took over: He hit her when she could not answer mathematics problems or did not know how to do her homework.

Looking back on his drastic behavioural change, Mrs Khoo said that it was probably due to financial strain and having to cope with the pressures of everyday living.

As time passed, domestic violence set in and became frequent.

He would beat his wife and eventually turned on their domestic worker as well.

Recalling the nights filled with shouting, screaming and sounds of things being thrown around the house, Mrs Khoo said that it always felt like she was living on the edge of a “terrible disaster”.

“It felt like I was living with a terrorist, like he wasn’t my dad anymore. I couldn’t understand why that was happening.

“I was always fearful, always on edge and tense, not knowing when the next explosion from my dad was going to happen.”

Apart from her own fears, she was worried for her younger sister who was just a two-year-old when her father started becoming abusive.

She found no answers when she turned to her mother, who was also suffering but was seen from her young eyes as unwilling to stand up to her husband or leave him.

“I cried with my mum and asked her what to do. But she told me, ‘Don’t you ever tell anyone about what's happening in our family’. I think there was a lot of shame,” Mrs Khoo added.

Not being able to tell anyone about her family situation made her feel helpless and “trapped”. She remembered crying a lot.

“No one taught me how to really take care of myself or respond to the situation. I recall being very depressed… and would just cry repeatedly.

“I was so scared to go home after school that I would cry out to God.

“Home was like a hell hole; I was scared that I was going to die in there.”

At 14, after experiencing another episode of her father’s verbal and physical abuse, something snapped.

She plucked up the courage and headed towards the police station, even though her mother had warned her not to get her father into trouble. The mother was worried that he would go to jail and they would be in financial difficulty.

“This was despite both my parents working and earning incomes. When I heard that, I told my mum that she couldn’t keep doing that and enabling the abuse,” Mrs Khoo recounted.

After telling the police officer what had happened, a personal protection order was filed against her father.

“I was very relieved and grateful to the officer who was very kind. He told me to keep (the report) and if my dad ever hit me again, to return and report it.

“That gave me the assurance that okay, someone’s still taking care of me. When I stepped out of the police station, my dad was actually standing outside.

“He was very sombre, quiet and didn’t dare talk to me or make eye contact.

“I felt really terrible because that was not what I wanted to do to my dad. I love my parents.”

That moment of courage brought her some relief, because he never used physical violence on her again.

HOW DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AFFECTED MENTAL HEALTH

By then, though, the traumatic experiences had left a profound impact on the teenager, who developed suicidal thoughts and self-harm tendencies.

Feeling helpless, “stuck and alone”, she wanted the pain to stop.

She was still living in a toxic environment because even though the physical abuse stopped, the verbal and emotional abuse continued.

At 22, she got married to Mr Joshua Khoo and they had their first child a few years later when she was 25.

Up to the time she got pregnant, she was still wrestling with dark thoughts and persistent low moods.

“When I found out that I was pregnant, I cried and told myself that no matter what, I’m determined not to let my daughter suffer the way that I did. It is her existence in my life that led me to go see a psychiatrist.”

After her consultations, she was diagnosed with clinical depression and complex traumatic stress disorder.

People who have this form of traumatic stress disorder usually have experienced long-term trauma.

It develops over months or years rather than over a single event, where there were repeated occasions where the victims had little control and were unable to escape their situation.

Supported by a Christian counsellor, a psychiatrist and a psychologist who kickstarted her healing process, Mrs Khoo underwent a combination of therapy and medications.

She was also supported by her husband, church mates and her faith, which eventually lifted the fog.

During this period, when her daughter turned one year old in 2010, the family of three moved to Thailand, drawn by a shared desire to do missionary work.

Her firstborn is now 14 years old and her younger daughter is aged 10.

The Khoo family continues to call Thailand home, returning to Singapore once a year for social visits.

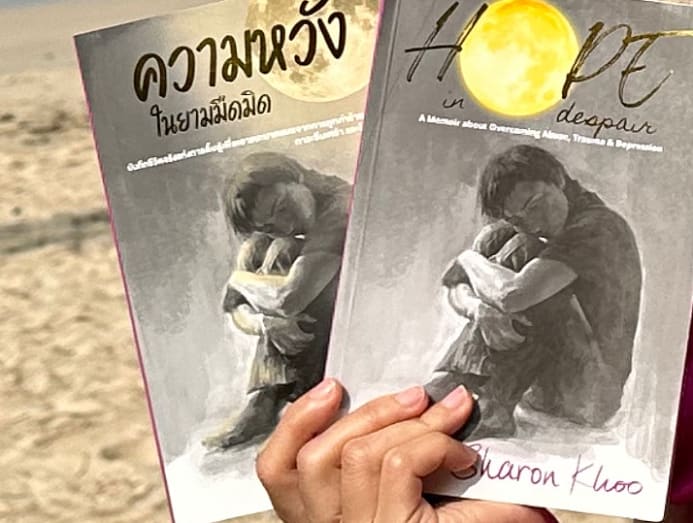

As part of her healing journey, Mrs Khoo wrote a book about the childhood experiences that her mother had told her to keep to herself.

Titled Hope in Despair, it chronicles her journey in overcoming clinical depression, complex traumatic stress disorder and the deep emotional wounds she sustained from domestic abuse.

Despite her initial hesitation of “putting myself out there”, hearing news of people dying by suicide spurred her to tell her story. She hopes that it would help others going through similar adversities.

Mrs Khoo said that she has forgiven both her parents, but still has some ways to go in reconciling with her father.

“I love my parents and have no animosity with them. There were so many times I felt so bad for them, and so saddened and ashamed of what had happened to our family.”

When asked what was her parents’ reaction to her book, Mrs Khoo said that they did not object to it. Her mother had told her that she felt ashamed and guilty for what had happened.

Her father had also apologised to her after the birth of her firstborn, but reconciliation has not been easy. She requested that he sought professional help, but he declined.

There were occasions when he was verbally abusive in front of her daughter, such that Mrs Khoo and her husband had to draw boundaries and not meet him in person to maintain their family’s safety.

For example, they would not meet both her parents together because that tended to trigger fighting and disagreements.

“I learned that forgiving him is one thing but reconciling is another,” she added.

“Just because you forgive, it doesn't mean you will have an okay relationship with the person who hurt you.

“If the person doesn’t know how to change or won’t actively seek professional help to change, he or she will just fall back on old habits and patterns.”

Her psychiatrist had commented that her father seemed to display symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder and borderline personality disorder.

Narcissistic personality disorder leads to egoistical behaviour and lack of empathy, while borderline personality disorder affects one’s ability to manage emotions.

Both personality disorders may involve dramatic, overly emotional or unpredictable thinking or behaviours, and interfere with how they relate to other people.

“But it was also definitely his unwillingness to be responsible for his own stress and frustration, and just letting it run free and wild in the house,” Mrs Khoo added.

My husband and children had to bear with me during the early years and watch me come out of the pain. But once I managed to do that, we could finally have a functional, healthy and normal family life.

Mr and Mrs Khoo serve in The Acts Church of Chiang Mai in Thailand and have also ministered in other countries including Australia, Brunei and Cambodia.

As a certified pastoral counsellor now, Mrs Khoo supports others being battered by their own storms.

Learning to overcome childhood trauma has shaped her perspective on her family life, and she is immensely grateful to experience what it is like to have a loving family.

Speaking of her husband and children, she said: “They are my greatest gift and achievement. With them, my family life is so different from the one I previously knew with my family of origin.

“My husband and children had to bear with me during the early years and watch me come out of the pain. But once I managed to do that, we could finally have a functional, healthy and normal family life.”

To others struggling with adversity and trauma, she wants to tell them that they are “worthy of care, love and all the right things in life”.

“No matter how out of control your situation may be or how you feel now, you have the free will and power to choose how you want to respond to adversity.

“No one, no abuser, bully or toxic situation can ever take away that power from you,” she asserted.

As a childhood abuse survivor, Mrs Khoo understands the importance of self-love in healing wounds of the past. Rewriting a life story begins from within.

“The most powerful, positive change is when you choose to love yourself, then you’ll do the right things for yourself and turn your life around.”

CRACKS IN ADOPTED AND BIOLOGICAL FAMILIES

Poised and articulate, Ms Nanny Eliana helms a medical and healthcare communications agency, which has offices in Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.

The Singaporean businesswoman also holds the position of chairperson of the Katong-Joo Chiat Business Association, which is a volunteer-led organisation that champions and supports the interests and welfare of business owners in the Katong and Joo Chiat area.

Deep beneath her confident exterior, though, is a girl who never felt like she belonged anywhere.

I always felt like no one could support me and I had to be prepared to move or for things to change.

Born in 1979 as the youngest of three daughters, she was given up for adoption at two weeks old to a Singaporean couple when her family had financial difficulties.

The early years of her childhood with her adoptive parents were relatively comfortable. Though strict, they provided material comforts and a stable family life.

When Ms Eliana was nine years old, her adoptive mother who was a homemaker died from cancer.

Her adoptive father, a civil servant, remarried about two years later.

After her adoptive mother died, he became stricter. Spending her pre-adolescent and teenage years under her adoptive father’s harsh disciplinarian ways was rough. His explosive temper and rigid curfews created a tense atmosphere at home.

“As a teenager at the time, it was impossible to have a conversation with him,” she recalled.

“He was not able to regulate his emotions and would fly off the handle easily, throw things around the house, ground me.

“He locked me out of the house several times.”

Ms Eliana had some suspicion that she was adopted because she did not look like her adoptive family members.

She never confirmed it until her adoptive father revealed the truth during a heated argument and told her to return to her biological family.

She was 18 then.

“Thrown back” to her biological family, the teenager had no choice but to start living with two older sisters, mother and father. Her father was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

Ms Eliana recalled that she could not really adapt to her new life, having lived in the comfort of her adoptive family’s five-room flat in a public housing block where she had her own bedroom.

The shift to the cramped quarters of her biological family’s three-room flat meant that she had to share a bedroom with her adult older sisters.

The lack of material comforts did not bother her as much as the lack of emotional connection and sense of safety.

Her mentally ill biological father thought that she was returned to the family to murder him.

Schizophrenia is a major psychotic illness where the sufferer is unable to tell what is real or unreal sometimes. The most common form is paranoid schizophrenia, where the patient has an altered perception of reality.

Patients have to take medication for symptoms of hallucinations that may include hearing voices, or of paranoia where they believe they are being followed or controlled, among other delusions.

Ms Eliana’s father did not consistently take his medication, which would then lead to episodes of abnormal behaviour and violence.

Recounting the times when her father punched her, she said: “I was caught unaware because he may be sitting quietly and suddenly, he would lunge at me.

“Back then, he used to wear rings with big stones on them. And he would punch me till the stones dropped off the ring, and the metal part of the ring cut into the skin under my eye.”

There were also times when he would charge at her with a knife. When that happens, she would lock herself in the bedroom.

“My sisters will berate him, telling him that it’s wrong to do that. But the thing is, he had no control over it.”

She added: “All I was thinking at the time was I needed to get out of there.”

Despite their blood ties, Ms Eliana did not feel a close bond with her older siblings. There were also moments when she felt that she was not welcomed or wanted.

“My sisters grew up together in hardship, so they were very close-knit. When I came into the picture, maybe they saw me as the ‘brat’, the third child who grew up in comfort, given the opportunity to go to university while they had to work to support the family.”

I was able to undo the belief that I couldn’t rely on anyone’s support. No matter how independent you are, how self-sufficient you are, we all need other people.

The painful and isolating experiences at home notwithstanding, Ms Eliana graduated from university, with her school fees funded by her adoptive father through the national social security savings scheme that is the Central Provident Fund.

Eager to build her career, she started work as a writer, only to realise that her working environment at the time caused her unnecessary stress.

About a year after graduating from university, Ms Eliana began freelancing.

She spent her waking hours outside home, writing at fast-food restaurants, meeting interviewees in their offices for fear that her mentally ill father would attack her.

Tragedy struck again when her biological mother died in 2005 from a sudden illness.

“She was literally the glue that held me to the family. So with her gone, the next thing I did was to move out,” Ms Eliana said.

The following year, she got married. Around the same time, she was offered a small space in a shophouse in the Boat Quay area for S$200 a month that she turned into her office.

She decided to build her own communications agency Bridges M&C, armed with a laptop bought with half a year’s worth of savings, a wall phone and dial-up internet.

Her marriage did not work out and they divorced after she met someone else, her current husband.

Ms Eliana admitted that a sense of safety and stability often eluded her.

“I always felt like no one could support me and I had to be prepared to move or for things to change.”

Her marriage to her second husband, who worked in corporate training at the time, had a tumultuous start.

During the global financial recession in 2008, he lost all of his clients. Ms Eliana was still building her business then.

She often found herself “feeling paralysed”. At the lowest point in her life, in 2011, she decided to get professional help.

“By then, my life felt like a reset button, starting over again repeatedly. It felt like the choices I made often led me to dead ends.”

Seeing a trauma therapist was the right move and Ms Eliana has kept up her appointments for the past 13 years.

When asked if there was a turning point in her life, she did not remember any particular huge breakthroughs in her healing journey, saying that she is “still a work-in-progress”.

“The ‘breaking free’ was incremental. It’s the little things like waking up and not feeling paralysed, and even when things happen, you are not overwhelmed by frustration or anger, such that you don’t make decisions in a way that doesn’t benefit you,” she added.

“I was able to undo the belief that I couldn’t rely on anyone’s support. No matter how independent you are, how self-sufficient you are, we all need other people.”

She did not get the support she needed from her adoptive or biological families, but Ms Eliana built her own network of support through her husband, friends and her long-time therapist.

Even within her own business, she set the tone for a supportive environment so that her staff members have psychological safety.

“People can say what they feel without being shot down and are not made to feel like they are disregarded.”

The media and communications industry has its shares of high turnovers, but most of her employees have stuck around. One of them is celebrating his 10-year work anniversary this month.

Ms Eliana has continued to keep in touch with her adoptive family, but lost touch with her biological family after they moved out of their old flat. “They have not reached out to me,” she said.

CRUSH THE CORROSIVE MEMORIES OR BE CRUSHED

Ms Eliana is hoping that her experience will help people with mental health troubles feel less alone in their struggles.

She has also contributed to a literary anthology (a collection of literary works) called Letter to My Mother, where she wrote about how living with a father who has paranoid schizophrenia affected her family.

“Being human is complex but there are ways for you to process your emotions if you get help.

“I think people don’t realise that others might have also gone through the same experiences until they hear someone else talking about it.”

Having benefited from therapy, she wants to encourage people to seek professional help.

To her, it is important to continue “feeling”, even the difficult emotions, and learn the skills to process them in a healthy manner.

“I’m able to experience more of the good stuff, like joy. I mean, how are you going to feel joy when you are wrapped up in anxiety, hurt and despair because that’s what you’re used to?” she asked.

The constant and unhealthy hark-back to past wounds can become a stumbling block to healing.

“Say, if my team decides to throw a birthday celebration for me, but in my head, all I'm thinking about is how I was hurt 10, 20 years ago, then I won’t be able to experience the support from the people around me.”

Ms Eliana said that people like her who have gone through traumatic experiences often store in their minds what has happened long after the incidents.

“There are people who may be 70 years old but their brains are still subconsciously stuck in pockets of trauma. I think therapy has helped me to process mine.

“My experiences taught me that the only way out is to process the trauma. You have to work through it,” she advised.

- To find the book Hope in Despair, go online here.

- Letter to My Mother is sold at leading bookstores.

WHERE TO GET HELP

- Youth centres under the Singapore Children’s Society

- RoundBox@Children's Society (Toa Payoh): 6259 3735 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

- Vox@Children's Society (Chai Chee): 6443 4139 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

- JYC@Children's Society (Jurong): 6566 6989 (Mon, Wed and Fri, 8.45am to 5.45pm)

- The Fort@Children's Society (Radin Mas): 6276 5077 (Mon to Fri, 8.30am to 5.30pm)

- Fei Yue's Online Counselling Service: eC2.sg website (Mon to Fri, 10am to 12pm, 2pm to 5pm)

- Institute of Mental Health's Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

- Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444 (24 hours) / 1-767 (24 hours)

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

- Silver Ribbon Singapore: 6386-1928 / 6509-0271 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

- Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788 (Mon to Fri, 2.30pm to 5pm)

- Touchline (Counselling): 1800-377-2252 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)