Gen Zen: Can virtual reality therapy help with our phobias and mental health problems?

(Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

SINGAPORE — A devious cockroach the size of a KitKat chocolate bar shuffled along the contours of my hand that morning, its antennae and hairy legs wriggling furiously as if to mock me.

I let out several expletives while trying to compose my tense body, to which my concerned therapist asked if I wanted him to push the button that would banish the revolting, virtual creature from existence.

I had been curious but sceptical of the effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) — a form of therapy where one is gradually exposed to the things, situations and activities one fears in order to overcome them.

While I didn't doubt that exposure begets familiarity, surely the knowledge that none of what I was seeing or hearing was real would prevent me from feeling fearful or anxious.

However, two sessions of experiencing multiple nightmare scenarios through a virtual reality headset changed that perception.

Mental health experts said that this practice is gaining recognition and popularity in various parts of the world including Singapore, although a brief search online for such services returned only two clinics where I could book an appointment for VRET.

Mr Sam Roberts, the founder of the Olive Branch Psychology and Counselling clinic where I underwent this therapy, said that several of his clients had benefited from VRET because it provides “a safe and controlled setting” for people to become accustomed to the object of their fear.

For instance, one woman who suffered from an intense fear of flying went through VRET to replicate being in an airport, boarding a plane and experiencing turbulence, takeoff and landing.

She initially had panic attacks even in a virtual setting, but Mr Roberts said that she eventually regained the confidence and ability to travel by air without overwhelming fear after about six sessions.

Concurring with the benefits and effectiveness of VRET, principal psychotherapist of Range counselling services Priscilla Shin said that its engaging nature and its “potential to transfer gains to real-life situations” make it an appealing therapeutic tool.

Can virtual reality really help us overcome our mental health problems? What are some of the limitations to the practice?

BENEFITS, EFFECTIVENESS AND SUITABILITY

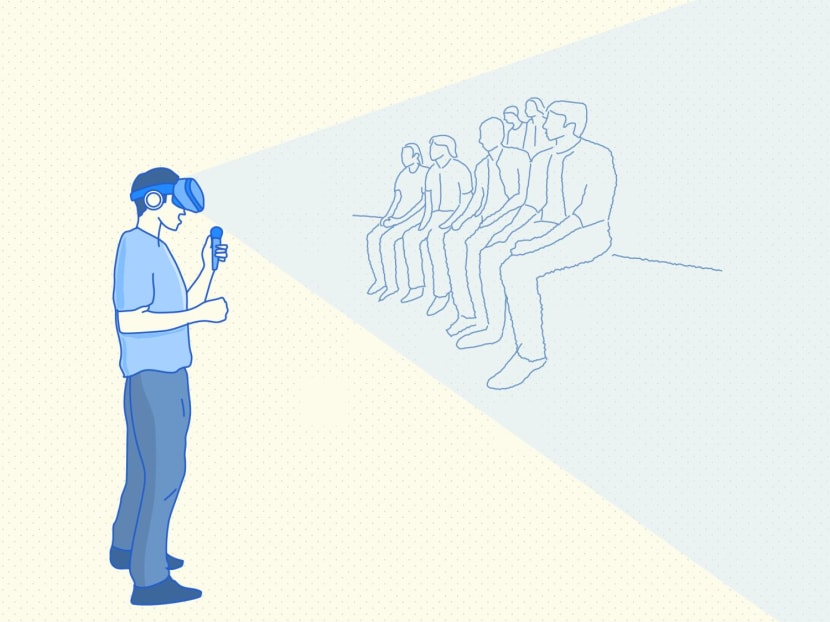

In addition to making “physical” contact with a cockroach during my therapy session, I also gave a speech to a hall full of strangers in hopes of reducing my fear of public speaking.

My therapist was able to adjust and control various elements in the virtual environment, such as where I was in the auditorium, the number of people present, and getting people to leave midway through my speech — all the while checking with me on my anxiety and stress levels.

This feature of customising the programme in accordance with a patient’s fears is one of VRET’s key strengths as it addresses an individual’s specific triggers, both Mr Roberts and Ms Shin said.

That is why VRET shines in treating specific phobias from fear of heights and specific animals to fear of enclosed spaces and public speaking.

It is also well-suited to tackling social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The accessibility of VRET provides another advantage. For one thing, although exposure therapy can be done without the use of virtual reality technology, this can be difficult to achieve for specific types of phobias.

It would be hard for those who fear flying to charter planes for such a purpose, for example, and those who fear wild animals might put themselves in danger if they try to interact with them.

For people with physical disabilities who have trouble getting to appointments, VRET could also be done at home provided the patients have the necessary equipment and access to their therapists.

Exposure therapy aside, the level of immersion that a virtual reality environment provides has also been proven by global studies to reduce levels of physical pain and anxiety.

One such study in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine — which put recovering burn victims in an icy, virtual world where their task was to throw snowballs at penguins — found that burn patients experienced 35 to 50 per cent less pain when undergoing medical procedures while immersed in virtual reality, compared with treatment with standard medications alone.

Indeed, I realised during my own VRET session that although the graphics did not come close to reflecting how real life looked, being placed in the situation itself was undoubtedly immersive — manifesting within me the same emotions that would surface if it were real.

LIMITATIONS AND PITFALLS

However, VRET is far from a one-size-fits-all solution, experts said.

I personally found the virtual environments immersive, for example, but others may not.

“If the virtual environment lacks realism or the technology fails to create a convincing simulation, it could diminish the immersive experience for the client. Poor graphics or technical glitches may hinder the therapeutic process, reducing the effectiveness of exposure,” Ms Shin said.

She added that some clients may not find the virtual scenarios as anxiety-inducing or realistic as real-world situations, limiting its therapeutic impact.

The virtual experience might also be uncomfortable or distressing for individuals with sensory sensitivities such as motion sickness, in which case the potential benefits of exposure therapy would be outweighed.

Mr Roberts said that although VRET provides an element of customisability, virtual environments are commonly pre-designed and may not precisely align with an individual's specific triggers or fears.

“The absence of complete personalisation could restrict the precision of exposure therapy in addressing personalised concerns.”

Other limitations include the type of mental health conditions that can be treated with VRET.

Mr Roberts said that VRET should not be the first choice for individuals with severe mental health conditions such as severe depression, psychosis or certain personality disorders.

For conditions that rely heavily on cognitive restructuring, or a deep exploration of underlying emotions such as complex trauma or certain types of mood disorders, VRET might not provide the nuanced therapeutic approach needed either, Ms Shin said.

“Additionally, clients with severe psychotic disorders or certain cognitive impairments may struggle to differentiate between the virtual and real world, potentially causing distress.”

IS VR THERAPY WORTH A SHOT?

Undergoing exposure therapy with the aid of virtual reality was appealing to me in many ways.

Even as I grew increasingly anxious with the deafening silence of a hundred people staring into my soul for my fear of public speaking, and became unwittingly nauseous with a cockroach making my hand its playground, I knew that I could simply take my headset off if it all became too overwhelming.

Not having to source for an actual roach or an auditorium full of people to attempt to conquer my fears was pretty neat, too.

Yet, virtual reality exposure therapy is ultimately that — a form of therapy.

A professional being by my side checking on me and asking questions that dug deeper into why I felt those fears in the first place gave me comfort and insight into my mental dispositions, and that was as important a part of the experience as immersing in virtual reality itself.

My fears of pesky insects and talking to crowds have not been debilitating to the point where my life and work are severely affected, but the evidence of VRET’s effectiveness sure makes it an appealing option if it ever gets to that point.