The 29-year-old who spent 12 years grappling with a hair-pulling disorder and finally shaved it all off

Since the age of 17, Ms Lynette Kua has grappled with a hair-pulling disorder. She tells CNA TODAY how it's given her a new outlook on beauty and identity.

Ms Lynette Kua (pictured) has spent over 12 years wrestling with trichotillomania, a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder centred on the act of repetitive hair-pulling. (Photo: CNA/ Ooi Boon Keong)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Standing at 1.83m, Ms Lynette Kua is impossible to miss anywhere. Seated across from me at a cafe in New Bahru near River Valley, the 29-year-old effortlessly commanded more than her fair share of attention, with her shorn scalp showing off a delicate tattoo curling faintly across her head.

After more than a decade of grappling with herself, she finally chose this hairstyle in October of 2024, for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

"I was very tired of wearing something to cover my head and constantly hiding," she said.

At first glance, her shaved head looks like a fashion statement. After all, the freelance dance instructor made a striking picture with her long, pearl, bow earrings grazing her sharp jaw and her tooth gems – tiny gemstones glued to her teeth – sparkling whenever she spoke.

In truth, her close-cropped style is the culmination of nearly 12 years of wrestling with trichotillomania, a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder centred on the act of repetitive hair-pulling.

Dr Lois Teo, head and senior principal psychologist of the psychology service at KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH), explained that a sufferer will typically pull their own hair out in stressful situations or when feeling bored.

Unlike many other mental conditions, trichotillomania has an immediate, evident effect on physical appearance. As a result, it can have a great impact on people's lives and identity, especially in Singapore where long, thick hair is often associated with attractiveness and beauty for women.

While Ms Kua's peers spent the last few years focused on high-powered jobs, next-level promotions or their next exotic travel destination, her biggest goal was uniquely simple.

"My greatest desire was just to leave the house without any head coverings," she said.

THE FIRST STRAND

My iced cold brew was sweating in the late morning sun as we commiserated on how terrible our junior college years had been for both of us.

Although we both found the academic stresses of junior college especially rough, that struggle took on a different shape for Ms Kua.

Following a "smooth-sailing" experience in secondary school, she began to experience significant academic difficulties in junior college. No matter how intensely she studied, she found herself drowning in failed tests and exams.

"It was the first time in my life where I worked very hard for something (but) couldn't achieve what I wanted," she said.

One afternoon, she was playing with her hair during another fraught study session.

"Your hands go up to your head and you're touching your hair," she said. "Suddenly, you find a strand that feels right. You hold on to it a little longer and after a while, you pull it out."

The sensation was strangely satisfying for Ms Kua. At that moment, the tension of the hair strand being pulled out from the follicle seemed to feel like a relief. So she did it again – and again.

"I didn't know that it was a problem."

Soon after, the hair-pulling happened more frequently and subconsciously. Eventually, she found herself entering a "trance-like" state whenever she was pulling her hair, where she would have no sense of time or what was happening around her.

It was only after she started seeing bald spots on her head that she realised in horror what she had done.

"I would start pulling and suddenly, one hour later, there would be a lot of hair on the floor. I didn't really know what was going on."

Ms Kua began spending a lot of time on finding elaborate ways to clip her hair to mask the growing bald patches, but this soon proved to be a poor stopgap measure.

Throughout the day, perspiration from the hot and humid weather would make her hair "shrink" and her bald spots more visible. Physical education classes, in particular, always made her extra self-conscious.

At home, her mother was finding large clumps of hair around the house despite Ms Kua's efforts to clean them up discreetly.

At the time, Ms Kua didn't understand why she was pulling her hair. Her confusion, combined with her fear of being "exposed", made it almost impossible for her to confront what was happening.

"I felt that it was very abnormal," she said. "That was why I couldn't tell people, because there were so many ways to deal with stress. Why did I pull my own hair out?"

Assuming it was stress-related shedding, Ms Kua's mother whisked her to hair-loss clinics and procured a variety of scalp tonics. She sat quietly through the root scans and bewilderment of trichologists, as well as hair and scalp specialists, who could find no physical reason to explain why she was losing her hair at such an alarming rate.

Finally, at the National Skin Centre, a psychiatrist named it: trichotillomania.

For many people, receiving a formal diagnosis can be a big relief. After all, clarity can often bring catharsis.

Not for Ms Kua, though.

"I felt like I got caught red-handed," she said. "Now the specialists know and there's nothing I can do to lie or deny it anymore."

Shortly after, she was also diagnosed with depression. Because of her condition, she was skipping school and falling even further behind on her academic work.

She was prescribed antidepressants and referred to a professional to receive counselling, but both measures seemed inadequate and unsuitable.

For instance, she stopped taking the medication after a while, because it left her drowsy and made coping with the demands of school even more difficult. Part of her treatment plan in therapy was to log on record every time she pulled her hair – a task that, at the time, felt too tedious.

"I wasn't in a good space to face it," she said.

THE DISCOMFORT OF DISSONANCE

Like many others who struggle with drastic hair loss, Ms Kua soon started wearing a wig.

Her first wig was synthetic and unnaturally glossy. Classmates assumed she was wearing wigs due to a "cancer thing" and avoided asking her about it; her teachers didn't mention or question it either.

For Ms Kua, the wigs were both armour and prison – a shield from the outside world, yet a constant reminder of her shame and never-ending paranoia that someone might discover the truth about her condition.

By the time she started attending university, she had learnt to source human-hair wigs that blended better and looked more natural, which brought her some comfort.

"For the first time after junior college, I felt like people were seeing me as normal again," she said. "I felt like I had a chance at a new life."

Despite her cautious hopes, she continued to struggle with trichotillomania. She found herself trapped in a vicious circle: The more stressed she got, the more she pulled her hair out, and the more she pulled her hair out, the more stressed she got.

At the same time, whatever relief the wigs brought Ms Kua was limited.

First, they did not come cheap. She paid more than S$1,000 (US$778) for a single wig.

Second, the wigs were held down to her scalp with her own hair. As the trichotillomania intensified, there was less hair with which to do this.

She also started to feel like whatever sense of normalcy the wigs offered her was often disrupted by a jarring dissonance, especially when someone complimented her on her looks.

"I was so fixated on the way I looked with the wig," she said. "I felt like I only looked pretty with long hair."

The wigs became more of a crutch. Eventually, she couldn't leave home at all without the wig properly in place, not even to make a quick visit to the shops below her housing block.

Living in Singapore's heat, wigs would be uncomfortable for anyone, let alone an avid dancer such as Ms Kua.

Having started dancing at the age of five, she had progressed to training for long hours nearly every day in her university years. Each time, her wigs would become heavy with perspiration, often tangling into unmanageable knots.

She kept three to four wigs in rotation, washing and drying them in turn on a near-daily basis.

Soon, she couldn't shake the growing discomfort and disconnect she felt whenever she wore the wigs.

"It was like this duality that I was living," Ms Kua said. "Outside, I was very cheerful and bubbly with no problems ... but back home, I was still pulling my hair."

To make matters worse, her wig would accidentally fall off occasionally.

During one incident she described as "horrifying", her wig slipped and fell to the floor in the middle of a dance performance. Burning with embarrassment, she grabbed her wig and ran off the stage.

Some time later, during an internship at a special-needs school, a child in the midst of a meltdown pulled her wig off in front of teachers and classmates. She had not previously disclosed her trichotillomania to her internship supervisors.

In a panic, she snatched the wig back and shoved it back onto her head before trying to carry on valiantly, but the damage had already been done.

"My whole world crashed," she said. "I still think that's why I didn't get (offered) the full-time job afterwards."

"IT COULD HAVE BEEN SO MUCH EASIER"

After two years of working in special-needs education, Ms Kua decided to pursue dance more seriously.

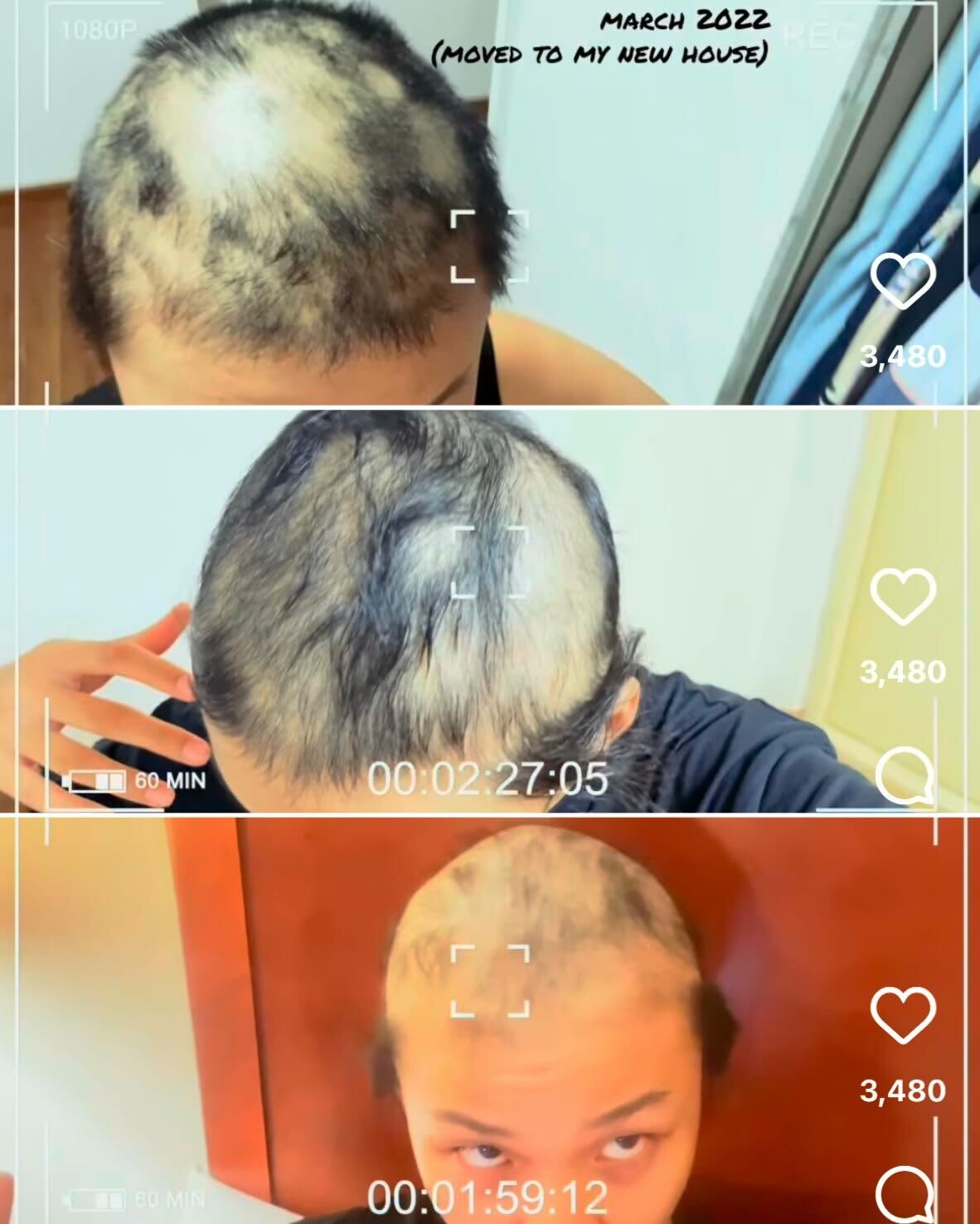

She embarked on training stints in South Korea and the United States in 2022 and 2023, but wearing wigs quickly proved to be more of a hindrance than a help.

Gripped with fear that her wig would come loose, she often found herself moving stiffly through the large, expressive movements required of her in street dance.

"The wig was restricting me," she said. "And I wanted to improve my dance so badly that it made me want to do something about (the wig)."

So one day, she tied on a bandana instead.

Underneath the cloth, her real hair was cropped unevenly, bald patches visible. She braced herself for the stares and questions, her mind racing with thoughts of how to dodge the unwanted comments.

To her surprise, none came.

"My friends just said, 'Oh, you cut your hair. Nice hairstyle'," she said with a laugh. "That's when I realised it was all in my head.

"I've been suffering for the past eight years, when it could have been so much easier."

From that moment on, bandanas became one of her primary ways to express herself. When I visited her home in July, she slid open two deep drawers crammed full with scarves of every imaginable size, shade and pattern.

Amid the variety, shades of indigo, cobalt and sky stood out most, practically spilling out of the drawer. Blue is Ms Kua's favourite colour.

Once she started wearing bandanas, she began receiving fewer compliments on her looks. Nevertheless, she felt it fulfilling to be a "more authentic version" of herself finally.

"People were seeing me and getting to know me on a real level," she said. "That was very liberating for me."

All the same, she found herself longing often for what many others take for granted.

"I was very envious of girls who could just leave the house with their natural hair," she confessed.

By 2024, after spending eight years in wigs and three more under bandanas, Ms Kua was exhausted with the endless fight to keep her head covered.

For all these years, one option had been presented to her: shaving her head entirely. She'd always resisted doing so in hopes she could recover and overcome the condition.

"To a girl, it's very scary to shave your head," Ms Kua said. "I just felt like, wah, I would be super ugly."

Last October, she bit the bullet and went to the barber to ask for a clean shave.

"At the start, I felt ugly when I looked at my reflection. It was very weird."

However, it immediately proved to be a significant relief for her trichotillomania. Having no hair to pull greatly reduced the urge to pull. Even when the urge did resurface, it could do no harm.

"After shaving my hair, I couldn't hide behind the way I looked anymore," Ms Kua said. "I had to face myself more truthfully and work to redefine what is beautiful to me."

However, years of pulling her hair out had effectively killed off many of the follicles on her scalp, meaning it was tough for hair to regrow at all.

That same month, she underwent scalp micropigmentation, a cosmetic tattooing procedure that creates the illusion of follicles on one's head. The procedure typically takes several sessions over weeks or months, depending on how much microblading is needed.

Since then, she has shaved her head weekly.

However, while this solution seemed much more promising, it brought new difficulties.

While her father admires her scalp tattoos and thinks her shaved look is "cool", her mother has found the change much harder to accept.

For Madam Hoe, who declined to have her full name published, bearing witness to her daughter's hair-loss struggle has been a source of much despair over the past several years.

"When I see Lynette suffering and in pain, I am also in pain," Mdm Hoe said. "If I could take over her pain, I would."

Even after Ms Kua found new relief in shaving her head entirely, Mdm Hoe still longed for her daughter to look, as she once put it, "pretty and gorgeous".

It has caused moments of friction between mother and daughter. For instance, Ms Kua adamantly refuse to take new photos of herself wearing wigs.

"I didn't want to any more," she said. "I told my mum I only want pictures of myself as I am now."

Smoothing over the tension remains a work in progress, she added. Yet, small gestures suggest a softening: While at the market, her mother will sometimes pick up a scarf for her daughter, so she can have more choices for her bandanas.

Ultimately, Mdm Hoe's dearest hopes for her daughter are beyond skin deep.

"If she is happy, on the right path and can eke out a living for herself ... I would be most proud," her mother said.

"I COULD MAKE OTHERS FEEL LESS ALONE"

In December 2024, Ms Kua travelled to Thailand to explore living and working as a digital nomad.

With a friend's encouragement, she began conducting filmed interviews in a spot often frequented by university students.

She would ask them questions about their views on hair and how much it matters in their estimation of a person's beauty and attractiveness. Finally, she would whip off her bandana to reveal her bald head and watch for their reactions.

She expected awkwardness, pity, even ridicule. Instead, she received empathy from most of her interview subjects.

Some complimented her style, saying she looked like a model. Upon hearing her describe her experience with trichotillomania, one man confessed that he had bipolar disorder.

Her biggest takeaway from the experience? "I learnt that there's a lot of kindness in the world," she said.

"A lot of times, no one is judging you. You are just judging yourself."

Encouraged, she began posting videos about her experience with trichotillomania on TikTok and Instagram. The response was overwhelming.

Comments of solidarity poured in. Many expressed relief and comfort at Ms Kua's openness in her sharing, as they had always thought they were the only ones grappling with this unique condition.

Parents of children with the disorder reached out for advice. Inspired by her example, some followers even shaved their own heads and sent her their photos.

"I know how alienating it is, having gone through it for the past 12 years," she said. "And (knowing that) I could make someone feel less alone, that feels very important."

All the same, Ms Kua isn't under any illusions about completely eradicating her struggles with hair-pulling.

Trichotillomania is widely acknowledged to be an incurable condition. However, it is treatable, Dr Teo from KKH said.

Such treatment often starts with early recognition and evidence-based interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and habit reversal training.

That being said, relapse is always possible, Dr Teo added.

Ms Kua said: "There will be good seasons where you don't pull for five years or even 10. But maybe one day, you could have a very bad episode and start pulling again.

"You won't (ever) be fully healed."

For now, Ms Kua is keeping her head closely shaved to give herself time to "kick this addiction".

"I don't think I'm ready to (grow my hair out) yet because I'm not confident that I won't pull it," she said.

Reflecting on over a decade of dealing with trichotillomania, she also felt that the real work was never really about stopping herself from pulling her hair.

Rather, it was about making peace with herself by letting go of the narrow definitions of beauty she once clung to and embracing a new understanding that beauty is "not even about physical qualities".

"Especially after shaving, I realised that hair is not a big deal, because I can always grow mine out anytime," she said with a shrug. "It's not necessary to make you feel beautiful."

Her wig now sits in a corner of her room, gathering dust. Once both a comfort and an encumbrance to her, it's now a relic of a life she no longer needs to live.

"I'm quite comfortable with the way I look," she said, describing it as her own style. "I want to look like this. It's not because I have a hair condition."

As the saying goes, what goes on in the inside shows on the outside.

"When I went back to dance, people around me were like, 'Wah, Lynette, there's this glow to you now. What happened to you?'," she said, smiling ear to ear. "I feel good about myself now, and it shows in my movement and the way I carry myself.

"I'm very much at peace with who I am now."