Once considered a golden boy, this ex-scholar left medical school to 'make his 20s count'

At 28, Mr Julian Low has gone from being a medical student to filmmaker to founder of a tai chi and theatre collective.

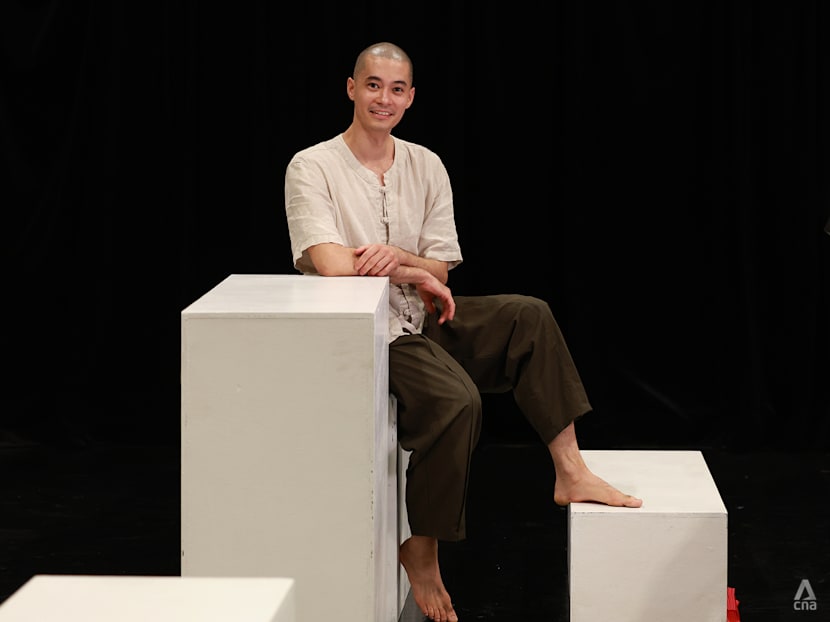

Mr Julian Low, 28, has gone from being a medical student to filmmaker to founder of a tai chi and theatre collective. (Photo: CNA/Raj Nadarajan)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

At a modest dance studio in a warehouse complex, accessed by clanking cargo lifts, Mr Julian Low was rehearsing for an upcoming performance by the theatre group that he and his wife founded.

It was a setting far removed from the days when he was training to be a doctor at the National University of Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine).

These days, the 28-year-old Singaporean trains in tai chi, a traditional Chinese martial art, and holds workshops and rehearsals for his theatre collective in this space located at the light industrial zone of Pasir Panjang.

It was in 2019 that he walked away from medical school after third year, so that he could run a video production company.

When I asked how he broke the news to his parents, his usually smiley face gave way to a grimace.

"I created a PowerPoint slide deck for them," he said.

The slides detailed why he wanted to leave:

- Being a junior doctor meant that he would have to put in very long hours at work, leaving him with little time for the entrepreneurial projects he would like to pursue while still in his 20s

- He had no interest in practising as a doctor after graduation, so if he continued and quit at the end of his studies, he would eventually have to repay the MOH Holdings a service bond in full, amounting to a high six-figure sum

Each new slide he presented deepened his parents' distress.

"They were begging me not to treat my life so flippantly," Mr Low recalled.

In Singapore, students at medical schools are bonded to serve in the public healthcare system and quitting early triggers a sizeable penalty.

In Mr Low's case, leaving then would mean having to pay back a hefty sum.

At the time, he was already involved in video production work. Since the startup he co-founded in early 2019 was doing well and he did not want to be in the medical field, he decided it was better to cut his losses there and then.

What made the decision harder for his parents to grasp was his choice to pursue video production work. For them, it was not just about the prestige of medicine but also rejecting an iron rice bowl.

His Singaporean father was an entrepreneur with mixed success and his mother was a piano teacher from Slonim, a town in the eastern European country of Belarus. The second of four children, Mr Low grew up in rented homes with his family.

When it became clear that he wouldn't budge, his relationship with his parents cooled. They lived apart, with Mr Low sleeping in a studio space he rented.

"There was a period of silence, where we contacted each other only every now and then," Mr Low said, lowering his gaze.

In the meantime, leaving medical school meant that he needed to find a way to pay the penalty.

THE GOLDEN BOY

Until then, Mr Low was – by conventional metrics – the golden boy of the family. Motivated by the idea of supporting those around him, he was a leader from a young age in various co-curricular activities in school, culminating in his becoming student council president at National Junior College.

"I'd say I had a bit of a saviour complex," Mr Low laughingly recalled. "I've always wanted to help everybody."

It was this spirit that led him, after guidance from his parents and those around him, to settle on medicine as a career initially.

"It's a noble profession," Mr Low said. "I liked the idea very much of helping people who are sick."

After gaining admission into NUS Medicine, he was awarded the NUS Merit Scholarship upon beginning his studies in 2016. The scholarship fully paid for his university tuition, although it did not exempt him from the five-year bond with Singapore's public healthcare sector.

He excelled in his academic pursuits while taking on extracurricular activities such as leading his team to victory at innovation competitions. He became the president of the Asian Medical Students' Association Singapore, representing all Singapore medical school students at home and internationally.

It was while he was in the thick of these activities that he began to question a future in medicine.

As with most medical students, he had a general idea of how demanding it is to be a doctor. However, experiencing it firsthand was a different beast.

THE TURNING POINT

In their third year of studies, NUS medicine students begin their clinical rotations. Mr Low was attached to a family medicine doctor at a private clinic in Sengkang.

"It was very strict," he said, remembering a particularly difficult day when the supervising doctor told him that "your clinical acumen is not there yet".

It dawned on Mr Low that in juggling all his external commitments with his medical studies, he lacked focus. The arduous path of a junior doctor meant that being a multitasker would no longer be possible.

"You must let go of all of your ambitions and focus on the job that you're doing, which is making sure patients don't die."

That reality, once abstract, was becoming harder to ignore.

Before making a final decision, Mr Low took a gap year – a break from studies – in 2018.

Having worked on a few video production projects on the side, he pounced on an idea: "Why can't we film doctors teaching about how they examine patients more often? Instead of just observing at the bedside, students can watch these videos to supplement their learning on how a doctor diagnoses a patient."

With friends from junior college, he co-founded a video production company in early 2019, creating educational videos for Duke-NUS Medical School and an anatomy professor, alongside corporate and influencer projects.

In the span of a single year, Mr Low felt that he had accomplished more than he had imagined possible. The experience made him confront what it would mean to spend more years in medical school.

"I was so pulled by other things," he reflected. "Why must I have the degree when, maybe, I don't need it?"

His mentor, a former junior college vice-principal, put it to him plainly: He could do whatever he chose, but if he closed the door to becoming a doctor, it would close forever.

The mentor also said: "You will buy something in exchange, which is the time of a young man in his mid-20s. Make it count."

Mr Low decided he would take a leap of faith and see how far he could go in the next few years.

Cases of students who break their bonds are not taken lightly and each appeal has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis by the authorities.

To pay back the penalty for quitting after three years of studies, he and MOH came to an agreement: He would become a video producer for NUS Medicine for a few years, creating educational videos for the medical students.

Mr Low said he is fully aware that his was an exceptional case where he was allowed to pay off his bond in this manner.

Juggling his full-time role at NUS Medicine with building his video production company, he gradually brought his business to a sustainable state.

However, the transition was not as liberating as he had imagined, as the stress began to wear on him.

"I got my freedom in terms of no longer being bonded to the school. I was my own boss. I could choose what I wanted to do," he said.

"But I was dying (inside)."

He coped by turning to alcohol and junk food.

Then, in 2022, he was invited to film a physical theatre warm-up by Ms Ranice Tay, a theatre practitioner and a friend he had met at a theatre workshop.

He remembered standing behind the camera, transfixed as the performers contorted their bodies in ways he could not fathom.

After the performance, he approached Ms Tay to ask about the principles behind their practice – a conversation that sparked his journey into theatre and tai chi.

THEATRE AND TAI CHI

On a Friday evening in June, I was part of a an audience of 100 or so at Stamford Arts Centre watching Mr Low's performance in I Am Finally In Love With The World, the debut production of Wushiren Theatre, the tai chi theatre group that he and Ms Tay, now his wife, founded in 2024.

The 75-minute performance centred on a young woman who returned to her late grandmother's house after a funeral wake. It then unfolded in a series of fragmented scenes, from a subdued puppet sequence to an intense wushu bout.

Experimental theatre often drifts into abstraction, but this performance maintained a central theme of grappling with grief and learning to come to terms with loss.

Watching Mr Low perform, his physicality stood out. He lowered his sinewy body to the floor with measured control, then rose in a single fluid motion.

He told me he draws inspiration from Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski, who saw the body as a vessel for expression. Mr Low sees tai chi as pushing this idea further.

Tai chi training, he said, empowers performers to hold a moment longer, build tension or shift the energy in the room without speaking.

His deep dive into tai chi began in 2023 under Ms Tay's guidance. By then, she had been practising for three years.

After quitting his video production company, Mr Low committed to a daily training routine he described as the hardest thing he has ever attempted.

Mornings began with hours of tai chi, which is a form of wushu, and afternoons were dedicated to theatre exercises.

When I asked about his shaved head, he laughed and said it was by choice.

"Six months in (with all the training), I was struggling. I wanted a fresh look to remind myself I chose this path seriously."

The symbolic gesture helped anchor his commitment. He credited his training with helping him to stave off his vices and three months ago, he was selected for the Singapore Traditional Wushu Elite Team which represents the nation in competitions.

Last year, he and Ms Tay formalised Wushiren – which means "I am human" in classical Chinese – as a theatre collective.

With their training sessions attracting attention from the arts community, establishing a formal structure helped them to run workshops, apply for grants and secure performance spaces.

When asked if launching a theatre collective felt risky, he replied: "Singapore is one of the best places to start anything."

He listed examples of the support available for the arts: the Art Resource Hub that supports freelance and self-employed artists, grants from the National Arts Council and informal artist networks.

He also attributed his openness to trying – and failing – as something he learnt from his youth. His mother had left her home in western Belarus decades ago, leaving behind a town she thought she would never see again.

"She knew how big the world was and she tried to inspire this thinking in us," he said. "You just need to have the bravery and the guts, the belief that you can make it because the world is big enough."

Grinning, he asked me: "How much money do you need to start a business?"

I hesitated and said: "Maybe S$50,000?"

"I think you don't need anything," he replied. "You can start from scratch. Ask for help, bootstrap with what you have. Singapore is a hub for entrepreneurship with much government support. You don't need your parents to be rich. You can do it."

LOOKING BACK TO LOOK FORWARD

As Mr Low's work in theatre deepened, so did his desire to understand his family background. He asked his parents about their stories, their roots and, for his mother, life under Soviet rule.

The more he learned, the more he recognised patterns in himself.

For example, he linked his lifelong desire to be a leader with what he called "the communist hangover" – where the top-down, resource-scarce environment cultivated a cultural reverence toward authority and a quickness to help others at the expense of one's well-being.

"In studying the past, you understand yourself better," he said, adding that such an understanding was vital in not letting history repeat itself.

This process also helped him to reconnect with his parents following four years of tension after leaving medical school. They bonded with him anew when they saw that he found fulfilment in his artistic work.

Looking ahead, Mr Low would like to see Wushiren growing both as an artistic collective and as a platform to help people do some self-reflection via their workshops and performances.

Occasionally, he still produces videos for medical education, but his heart now lies in theatre.

Asked whether he regrets the years he spent in medical school, he shook his head.

"The notion that three years were wasted is wrong. It was three tremendously good years," he said, pointing to the friendships he made, the doctors with whom he remained in close contact and the enjoyable course content he learnt.

"Looking back, I still believe the decision was right for me."

He elaborated that, even today, his medical school background still pays dividends.

He continues to make educational videos for NUS Medicine. Recently, the dean of the medical school wrote a recommendation that enabled him to pursue a master's degree in arts pedagogy at LASALLE College of the Arts without a bachelor's degree.

As the interview drew to a close, I asked him why he was willing to talk openly about being a medical school dropout and expose himself to criticism.

"I recognise that not everyone has the same freedom to take such risks. but I hope that this experience of mine encourages those who do, but feel afraid, to consider what's truly meaningful to them."