Illiterate in Singapore: When you can’t read or write English in one of Asia’s most English-literate countries

What’s life like for adults who can’t read or write English? The series Write of Passage sheds some light on their hidden struggles – and over 12 weeks of intensive training, challenges them to achieve some goals.

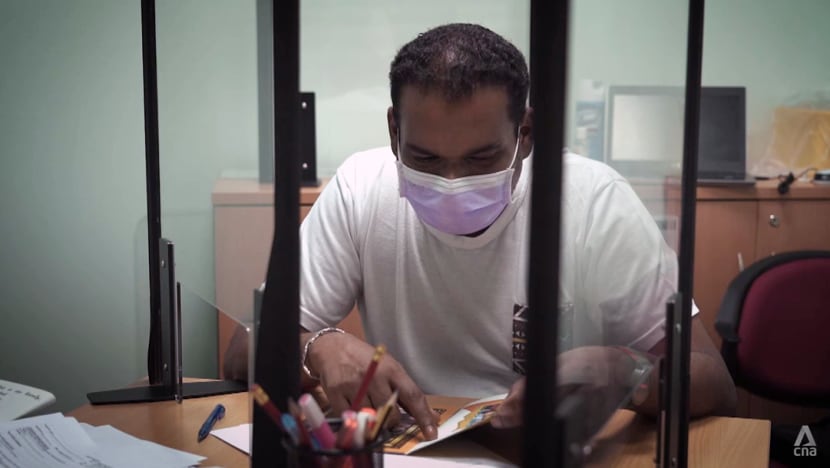

(From left) Jegathasan Pushpangathan, Jimmy Tan, Stephen Chng and Tng Xiao Ling put their best foot forward.

SINGAPORE: At first glance, 33-year-old Stephen Chng looks like any other professional you’d meet on the street – he works as a marine engineer, owns a car and is happily married to Faith, his wife of nearly five years.

But there’s a part of his life he’s guarded about: He struggles to read or write English.

Assessed to have the reading level of an eight-year-old, Chng has trouble making out the signs and labels so prevalent in daily life: Road signs, food labels and even text messages. When he first started dating his wife, he would send her texts like “repple massage”, when he actually meant “reply message", he remembers with a sheepish grin.

He has hidden his struggle well: In his job, which requires mainly practical work, he gets his wife to help him the few times he has to type out reports. When he drives, he relies on Google Maps to read the signs aloud for him. The few road signs he can read are the ones that are names of MRT stations he frequents, after seeing them repeatedly on his commutes.

Chng is one of the participants in the series Write of Passage, which features adult Singaporeans who have gone through life without knowing how to read or write English.

Earlier this year, CNA put out a casting call for people interested in 12 weeks of intensive one-to-one coaching to join the programme. Chng was one of almost 100 people who responded.

A HIDDEN PROBLEM

Singapore is known to be one of the most English-literate countries in Asia. But adult illiteracy may be more common than expected: According to the Department of Statistics, in 2020, there were about 283,000 Singapore residents aged 15-64 years old who are illiterate in English.

Who are they?

Some are school dropouts like 60-year-old Jimmy Tan, who left school in Primary Two. A former gang member who was in and out of prison for more than 20 years, he was determined to turn over a new leaf when he was released almost two years ago.

But he realised the world had passed him by. “All Singapore, a lot of places, all changed,” he said. “The signboards all English.”

In his previous life as a gangland “big boss”, everyone spoke in Mandarin or Cantonese – never English.

“When you talk in English, people would say, ‘Wah, what a show-off. Arrogant',” he said. “Now in Singapore, you talk to people, open the mouth… all in English.”

He was assessed to have the reading and writing level of a seven-year-old. By the end of his course, he wants to sing a song in English – Amazing Grace, as a testament to his decades-long journey of redemption.

Some are individuals like 40-year-old Maya, who wished to be known only by her first name. Until three years ago, she could read, write and even speak normally. A stroke robbed her of the ability to do all this. Her condition, known as aphasia, means that the region of the brain that handles literacy is damaged.

About one-third of all strokes result in this condition. While the damage cannot be reversed, speech therapy can help sufferers regain some ability to communicate.

There are also others who completed primary school and went on to higher education. According to the Ministry of Education’s syllabus, they should be able to read, interact, respond to and critically analyse a range of texts used in everyday life by Primary Six.

Why, then, are they still unable to read?

Chng remembers the sea of red in his exam papers in school. Numbed by the criticism from his teachers – one of whom, he said, made fun of him in front of the other students – he felt too embarrassed to stay in the classroom.

“Every time the lessons started, I would automatically just walk out,” he said. This went on for eight to nine months in primary school. It was his maths grades which pulled him up and allowed him to graduate with a polytechnic diploma.

Students in school get regular practice in reading and spelling, and this will tide them through exams, said educational therapist Rachel Toh. But at home, she said, they may not have an environment which exposes them to the English language.

“Not every home has magazines. You don’t have storybooks in every household,” she said. “So, the exposure isn’t there. When you’re not exposed to these words frequently, it just doesn’t stay in our long-term memory.”

You can’t read, but you can be very eloquent, you can be very well-liked among your friends because you are generous and genuine as a person.

From there, reading becomes a chore. This means that even though they come across words in their daily lives, they might tend to just skip them, she added.

GETTING THROUGH LIFE, HIDING THEIR LACK

Individuals who cannot read and write may compensate with something else – their personality.

“You can’t read, but you can be very eloquent, you can be very well-liked among your friends because you are generous and genuine as a person,” Toh said.

Tng Xiao Ling, 35, is one such person. She spoke Mandarin at home and said she never picked up a storybook and “never paid attention in school”.

She hides her lack of language ability behind a smile: She is jovial, often laughing at herself when she mispronounces a word.

“If people laugh at my English, I just smile back at them,” she said. “It’s okay to let people laugh… Before they laugh at me, I laugh at myself first. Maybe then, it won’t hurt so much.”

Assessed to have a reading age of seven, she joined the programme hoping to help her daughter in Primary Five, Yingxin, with her spelling test words.

“I feel that it’s very hopeless when I don’t know how to teach my girl,” she said.

Before they laugh at me, I laugh at myself first. Maybe then, it won’t hurt so much.”

At the time the show aired, Tng worked at a call centre, where she had to type words on the computer. She found ways to cope. She remembers one incident where she wrote the letters “O” and “D” to indicate that a particular vehicle was an Audi.

WATCH: Mum Learns English To Help 11-Year-Old Daughter With Spelling (4:21)

In the same way, Jegathasan Pushpangathan, 40, has found ways to cope with his inability to recognise even simple words. This is no mean feat for someone with a reading age of six. At the time the show aired, he had worked as a food and beverage executive at a hotel restaurant for 15 years and had to take orders and reservations regularly.

He has a “secret language”: When a customer orders waffles, for example, he will scribble “wewk” on his notepad.

“I’ll write wrong English letters only I can understand,” he said. “That’s why I don’t share what I write.”

He does the best he can, asking his colleagues for help along the way. But there is one thing that makes him lose all confidence: Laying out nearly 100 food tags for the restaurant’s buffet line.

“If you give me a table to carry, I will do it for you,” he said. “But if you ask me to take up a pen and paper… it’s very heavy.”

His supervisor described Jegathasan as a good worker and role model for his juniors, and would like to promote him. But Jegathasan himself is hesitant. "If he wants to give me a promotion, I need to do emails… I can’t even do the food tags, how can I touch emails?”

As for Chng, it was perseverance that got him this far. He failed his driving theory test thrice. The fourth time, he practised for more than 36 hours, memorising almost 190 out of the more than 200 questions in his basic theory handbook, and more than 300 of the 400-odd questions for the final theory test.

He also learnt not to draw attention to his limited vocabulary by trying not to speak too much. “He worries that he might say something wrong,” said his wife, Faith. “I tend to speak up more so I can prevent misunderstandings with my family and relatives, to put his message across in another way.”

THE TRAINING — AND THE REVELATION

As part of the programme, participants were matched with teachers for one-on-one training for 12 weeks. They learnt the basics, like phonics and how to break words up to make reading easier.

But there were also challenges designed to help participants express themselves better and build confidence, such as a dramatic reading of the children's classic, Little Red Riding Hood, on stage in front of their loved ones.

Some had to overcome self-doubt – and the doubt of those around them.

As the oldest participant, Tan struggled with classroom lessons and found it hard to practise on top of his day job as a cleaning supervisor.

Tng, on the other hand, faced resistance from her family when she joined the series. “My husband said… ‘Now then you learn English. At this age, what’s the use?’” she recalled. “I had to explain to him that if I know English, I can teach my girl in the future.”

WATCH: Help, I Can't Read! Confronting English Illiteracy In Singapore (48:08)

Jegathasan, too, had for many years wondered “what (his) problem was”. Growing up, his mother had sent him for tuition and trusted that he would study hard. “But Jega didn’t study,” said Mageswari. “I was disappointed.”

As an adult, he had paid for English lessons to boost his literacy. But after seeing no improvement after six months, he gave up.

During the programme, however, he made a discovery: He was dyslexic.

The diagnosis – from a series of tests during the initial assessment of his abilities – provided a much-needed answer to the question that had always bugged him. “I can tell myself I am not stupid,” he said.

If you give me a table to carry, I will do it for you. But if you ask me to take up a pen and paper… it’s very heavy.

When series host Diana Ser accompanied Jegathasan to break the news to his family, his mother and sisters expressed only regret and sadness. “I blame myself,” his mother said.

“If she had known that earlier… she might have put in extra help for him,” added his sister Gyathri.

THE FINISH LINE

The participants completed their last lessons in August, and the final episode of the series aired this month.

By the end of the series, they had showed a marked improvement and managed to achieve their goals. Chng wrote a letter to his wife and Tan sang Amazing Grace in front of an audience, for instance.

WATCH: Our Last English Lesson: What's Our Progress? (47:24)

The final assessments showed that within the three-month period, Tan and Jegathasan had improved their reading ages by four months. Tng had jumped eight months.

Chng – who had to cut his training short by a month after being sent overseas for work – improved by a full year. He’s even been able to write work reports on his own while overseas, without having to call or send voice messages to his wife in Singapore for help.

Tan now takes pride in the fact that he can translate English news articles for his elderly mother.

Even though the cameras have stopped rolling, the participants continue to make progress, some with the help of generous viewers.

Tng, who was able to successfully read out half of her daughter’s spelling list by the end of the series, is still continuing with her lessons. Her tutor has agreed to continue helping her for free, but the pair have shelved plans to meet until the pandemic eases.

She is now more confident using English in daily situations. When she ordered food in the past, she would ask the waitress to speak to her in Mandarin, she told CNA Insider in a follow-up interview.

“After the lessons, I’ll make more effort to read the menu,” she said. “If the waitress speaks English to me, I will answer her in English.”

Jegathasan, who received 20 sessions of specialist help from the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS) over the 12 weeks, was eager to continue his lessons.

His tutor estimated that he would need another 20 sessions to ride the momentum of his progress. But such specialist help can cost more than US$100 (S$135) per hour, and this was money he did not have.

Several viewers wrote in to offer help. Many wanted to donate money to defray the cost of the lessons, while others offered to teach him for free.

This prompted the DAS to start a Giving.sg fundraiser to help Jegathasan. So far, more than 60 donors have contributed enough to cover 20 more sessions for him.

“I am happy,” he said. “Thank you. Thank you so much."

The positive response from viewers was, for series producer Tang Hui Huan, assurance that the team had done their jobs well.

“We were always treading a thin line between encouraging empathy for these adults, and setting them up for mockery,” she recalled. “Some of our more camera-shy participants were quite open with the team about their fears from the first day of filming.”

They wondered: “If I reveal my weak point to the world, will people judge my ability to do my job properly? Will they mock me or criticise me?”

Tang said these were the very real concerns that her team worked hard to address. “I am glad we made it work,” she said.

Tang and fellow producer Sharifah Alshahab had set out to bust misconceptions about adult illiteracy. When they were looking for people to join the show, the team had come across “incredulous” reactions, with people passing comments such as “illiterate adults must have been lazy in school” and “I thought only old people can’t read and write English”.

“Just because the majority of us are fine, doesn't mean we shouldn't pay attention to those who are struggling,” said Sharifah. “Through the series, we prove how much difference three months can make when we turn our focus to those who might need... suitable intervention.”

Watch Part 1 of Write of Passage here.

Watch Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

Editor's Note: This story has been edited following clarifications from the Department of Statistics on the number of Singapore residents who are illiterate in English.