‘I felt like an alien abandoned in this world’: An autistic man’s quest to be ‘human’

While autism is regarded as a lifelong disability, Eric Chen wants to defy its limitations and be seen as equal to neurotypical folks. But not all autistics think this way — some call for accepting the disability as it is.

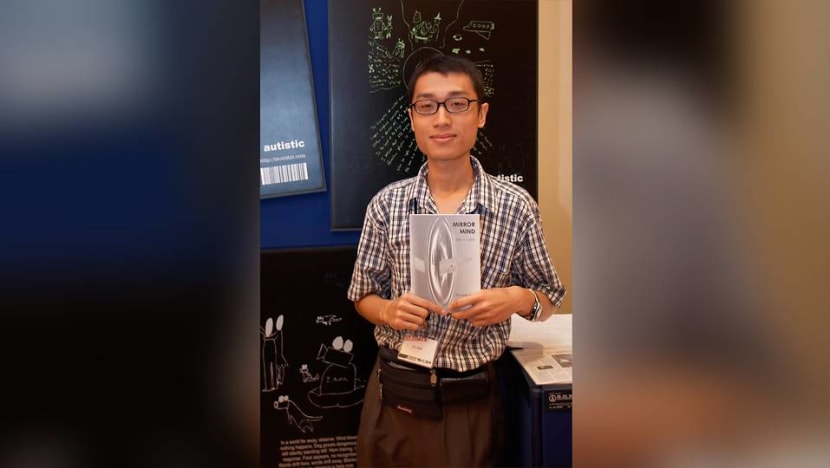

Eric Chen, 38, was diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder when he was 18 years old. (Photo courtesy of Eric Chen)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Through his childhood and adolescence, Eric Chen was sure he did not belong on Earth.

He had hoped for a spaceship to descend and take him back to his “home planet”. And he is hardly joking.

“I felt like an alien abandoned in this world,” says Eric, now 38. “Unfortunately, there’s no radio I can call on for help. I’m basically stuck in this world to put up with all these weird, irrational people.”

Put up he did — until he was 18 years old and obtained a diagnosis. On the brink of adulthood, he finally put his finger on why he could not make sense of the world. He had an autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

“I needed an answer so that all the bad things that had happened to me, I can (attribute) to autism,” he tells CNA Insider. Things like being unable to tie his shoelaces, understand instructions or make friends.

He looks up ever so slightly, as he does every time he finishes a thought. With 20 years of “work” done on himself since his diagnosis, making eye contact is less of a chore.

That work, he describes, includes “accepting that he’s part of the human race”, learning to communicate and “awakening to emotions”.

ASD is a developmental condition that involves persistent challenges in social interaction, speech and non-verbal communication, as well as restricted or repetitive behaviour such as rocking and spinning. Symptoms typically appear from childhood.

As the name suggests, there are varying degrees to which autism presents itself. Eric is a verbal autistic with low support needs, unlike the broad brush that autistics are typically painted with: “Those who flap their hands and scream.”

And this is an inside look at his autism, how he embraced it, transcended its limitations and how he wants to help others do the same, if they are so inclined.

READ PART 1 OF A SERIES ON ADULTS WITH AUTISM: The invisible struggle of people with high-functioning autism — and workplaces that hire them

GROWING UP ‘DISCONNECTED’

Before his “awakening” (and there were many more, he adds), Eric would have described himself as robotic.

Puzzled as to how the world worked, he shut himself off and was “driven by instructions” from his parents or teachers. On the outside, he was quiet and compliant. But on the inside, there were bizarre sensations he could not process, much less describe.

“Processing the meaning and interpretation of words, and finally a translation of the words into action, is a complicated process that people take for granted,” he said. “But autistic people often struggle with it.”

And so he always made mistakes. When his mother asked him to wipe the table, he would wipe the entire table, instead of the one spot of spilt water.

“My mother would say things to me like, ‘Your boss will fire you next time. I have to repeat myself so many times for you to know what you should and shouldn’t do. Just listen and follow instructions,’” he recalls. But to him, he was doing as he was told.

When his teachers gave him homework, he would be able to take down only half their instructions.

“There’s this strange thing. It’s like you’re listening in English and then suddenly the English becomes some foreign language. And whatever the teacher says doesn’t get written down,” he says.

No one seemed to stop to think about whether he had a disability — only that he was clumsy.

And that thing called feelings? It was a more ethereal concept than him being an alien.

“Maybe not to all autistic people, but to those like myself who are disconnected, it feels like there’s an invisible parallel universe where there are things like emotions, where relationships exists, where people see things I can’t see,” he says.

“I may feel some emotions, but they’re quite vague. … It’s like wearing thick gloves and trying to feel something, but you can’t feel it properly.”

When classmates picked on him, passing his schoolbag around and taunting him about it, he had no idea it was bullying. He had no idea he was feeling a rush of anger. He could only wait for it to “disappear into a black hole”.

NOT AN ALIEN, JUST AUTISTIC

Eric threw himself into books, chores and homework — notwithstanding his fumbling — or observed insects because the world was “aimless” and “disconnected”.

“I just wanted to focus on things that can bring coherence and order. And that would just be to do things,” he says.

Little did he know that reading was going to help him accept this “irrational” world, and his place in it.

At Secondary Three, a friend lent him The Einstein Factor, and it flicked the first of many switches in him.

“You don’t have to rely on others to make choices when you can choose your own future,” the book read, roughly paraphrased. “That insight changed everything,” he recalls.

“I suddenly could think for myself. So instead of freezing there and waiting for inputs, I could unfreeze myself and start solving problems.”

He started questioning things he was told to do, though that had some “bad side effects”. He wondered why he had to study, and his parents and teachers were not pleased.

He told his literature teacher, for example, that literature was “literally all fake news of people, some of whom don’t even exist” and that he did not want to study it any more. “I had to apologise,” he quips.

After completing his logistics engineering and management studies at polytechnic, he chanced upon an article on “the geek syndrome” in Silicon Valley, where cases of autism and Asperger’s syndrome in children were surging.

In layman’s terms, Asperger’s syndrome is a milder, less disabling form of autism characterised by social awkwardness, a poor understanding of social cues, and few emotions displayed. People with Asperger’s syndrome may have high intelligence and above average verbal skills.

(Since 2013, it is no longer classified as a diagnosis of its own but a part of ASD.)

As Eric researched into Asperger’s syndrome, he identified with the symptoms and, in 2001, sought an official diagnosis. Finally, he could “accept that (he) was human”.

While the diagnosis gave him clarity and an understanding of his individuality, it did not seem to be the case with his friends and family.

“Most people don’t understand what to do with this knowledge. A number of people would say things like, ‘You look normal. How can you be autistic?’” he cites. But he did not know how to explain or advocate for himself.

Just before he entered National Service in 2002, another book, Conversations with God, came along.

“It inspired me to look at the world in a different way,” he says. “I don’t see myself as serving a sentence where I have to suffer.”

He adds, however, that he is “not making any claims in support of or against God”.

EMOTIONAL BREAKTHROUGHS

Since Eric’s epiphany, a series of breakthroughs have happened for him. Previously he thought people (himself included) were simply two-dimensional objects. Then on the day of his grandfather’s funeral, he realised his relationship with his family had “depth”.

He was the eldest grandchild, and he was to lead the rest of the grandchildren in the procession. “At that point, I realised what it was like to be a brother,” he says. And he felt a deep sorrow.

“In the past, I didn’t understand this whole concept of biological families and why your mother or father was important,” he adds.

“I wasn’t really a grandson before, but at least on this day, I’d be a grandson and do my duty faithfully.”

One aspect of ASD is the inability to relate to others. So for him, it felt as if the world of “relational meaning” had opened up and he was taking his first baby steps.

While people “usually” think of emotions as “hindering them from being rational”, he wanted to “go the other way … to develop”. “(Being rational) was hindering me,” he says. “I had to be more emotional, more imperfect to become more human.”

He has even added rage to his emotional vocabulary.

Then, some three years after his diagnosis, “the world came together” for him. He was at a bus stop crowded with people, and he suddenly felt as if he was “reading their minds — what the person might be thinking”.

“I’m like, what happened? This is so strange,” he recounts.

Was it empathy? “Much deeper than that,” he says. “It turns out that relational meaning is a deeper understanding of how we’re conscious of the world.”

He had reached the “final gate” to the universe of non-autistic, or neurotypical, people. Once he could relate to this group, it was as if his sensory difficulties had also been tamed, he says.

He could “sense relative positions in 3-D space and was rid of (his) extreme clumsiness”. He could look people in the eye longer without feeling uncomfortable.

He did not have to go through several steps in his head before understanding non-verbal cues. It came to him almost as second nature, but not completely. “It may still be limited,” he says.

“Because most (neurotypical people) were already used to (understanding non-verbal cues directly) when they were kids. They’re very familiar with it, but I only came upon it in the past few years. So I still need a lot of practice.”

ERIC CHEN TODAY

Eric is now a freelance life coach, photographer, information technology consultant, psychometric testing consultant and full-time autism advocate.

He wants to help “autistics find their own way in life that allows them to thrive”. To this end, he co-founded the WhatsApp Autism Community, a one-stop resource where interested parties can join chat groups for support.

The groups’ discussions include general knowledge, investments, insurance, sports and autism advocacy. There are also carer-focused groups where participants can talk about schooling, NS and relationships, to name a few.

Eric runs the community with nine others, eight of whom are autistic. His hope is that more autistics like him will be engaged, as they “hold the key to helping those with low support needs”.

“There’s this vast pool of hidden resources: People who’ve managed to … adapt,” he cites. They have found a way to get jobs, have meaningful relationships or start a family, “doing things that (neurotypical people) would naturally do”.

“Lawyers, doctors, educators, fitness trainers — all these people from all walks of life write to me. They just don’t want to tell people they’re autistic,” he says.

“Why would they want to … be exposed to discrimination or have problems with their insurance applications?”

READ: They have the skills and qualifications. So why can't these disabled people find good jobs?

For his part, he would like to create change, even at “great personal cost to (himself)”. He says: “This is a calling for me — to find a way for autistic people who are ready to enter the neurotypical, non-autistic world.”

He knows his ideas are controversial.

Even as more autistics learn to advocate for themselves, some feel that they should not be measured by neurotypical standards in the first place. In the autism community, ableism — discrimination in favour of able-bodied people — is a cause for concern.

In fact, the term “high-functioning”, which has been used a long time to describe people like Eric, has become a thorny issue because it measures the autistic person’s function against a neurotypical person.

Some say this label has sidelined the needs of “high-functioning autistics”, as it suggests that they function well in spite of their autism. The term “low support needs” is now preferred.

Rather than “curing” autism, some advocates say that autistics should be embraced as part of mainstream society. This means providing them with support, be it for their sensitivities or social anxieties, so that they can participate in the community.

Other autistics whom CNA Insider spoke to emphasised that calling them “persons with autism” is not helpful. Many are proud, if not relieved, to be autistic and embrace this word rather than perceive it as denigrating.

‘BALANCED’ SUPPORT NEEDED

While Eric welcomes more support for ASD, like the Autism Enabling Masterplan launched this year, he is a little concerned.

“This support has to be balanced, (so) that we don’t make it the expectation that autistic people can always count on support from the non-autistic world,” he says. “They should be inspired to break the limitations they have.”

For example, in the long run, autistic job coaches should, ideally, be the ones engaged to guide other autistics through the workplace environment, he cites.

“If you’re an autistic job coach, you understand based on your past experiences why your new autistic colleague would have trouble and how you can coach that person better.”

True equality is a step further — when autistic job coaches can help autistic and non-autistic colleagues alike, he adds.

On the question of making exceptions for autistic individuals, he thinks it is “a chicken and egg issue”. He notes: “People have certain ideas (about autism) that are very deeply ingrained.”

For him, there is no time to waste waiting for the other side to change. In calling on autistics to enter the neurotypical world, he wants people to have options.

“For autistics with limited capacity to learn, don’t force them to change. They have needs that’ll be with them for the rest of their lives,” he says.

“But there should be support for people who’d choose to do what disability usually prevents them from doing. … Yes, I’m proud of who I am (as an autistic person), but I know how I am doesn’t help me.

“The way I was interacting wasn’t helping. The way I communicate with people has to be improved … not because I want people to accept me, but because I want to work with other people to create change, to make the world better.”

People had long made him feel as if he needed fixing because he was not behaving properly. To him, “the feeling was mutual”. But the neurotypical world became less irrational when he started to understand it.

What he wants is to connect autistic and neurotypical people. “Building that bridge allows me to see them, and maybe allows them to see me too,” he says.

What he wants is to be seen as an equal.

Only at the end of a three-hour-long conversation does his social awkwardness show a little (based on neurotypical assumptions). Before parting, he hesitates, unsure of what to say. He settles on asking politely where the restroom is and waves goodbye.

He has spent 20 years building that bridge. Some of us are just getting started.

This is part of a series on adults with autism navigating the neurotypical world of work, marriage, and identity. To learn more about Eric’s work and services, visit iautistic.com. Also, read about the invisible struggle of people with high-functioning autism — and workplaces that hire them.