commentary Commentary

Commentary: The end of unrestricted commerce and the dawn of the great US-China disentanglement

This new phase in geopolitics will be marked by a US-China decoupling in the technology sector, says NUS Business School’s Alex Capri.

Flags of the United States and China. (Photo: AFP/Fred Dufour)

SINGAPORE: The era of open, unrestricted commerce between the US and China has come to an end.

While the past three decades featured a period in history with arguably the most rapid, massive and spectacular transfer of wealth from one major economic power to another, the next phase of Sino-US relations will be defined by barriers, prohibitions and restrictions.

Firms have been slow to grasp the magnitude of this development. Recently, however, increased talk about a so-called “decoupling” of the two economies has begun to register alarm.

Looking ahead, multinational firms will have to double down on risk management processes that deal with increasingly nationalistic policy agendas, including sanctions and export controls, data protectionism and state-sponsored cyber intrusions.

Consequently, global value chains will fragment and will need to be ring-fenced into selective, localised business clusters. In this regard, the golden era of globalisation, as the world has come to know it, is over.

But how realistic is a full-scale US-China economic decoupling?

READ: Joseph Nye's commentary on the cooperative rivalry of the US-China relationship

A DECOUPLED REALITY

Trying to disentangle global supply chains and complex business agglomerations that have taken years to develop conjures up visions of economic and financial mayhem.

But on grounds of national security, a decoupling of the US and Chinese technology sectors is inevitable. The question is not if it will happen – it already is happening – but to what extent this will take place.

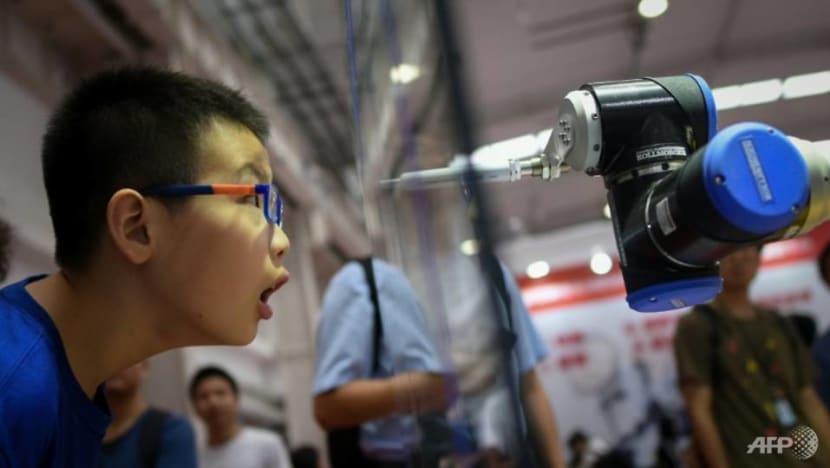

The most vulnerable firms are those that have become intertwined with the Made in China 2025 plan, Beijing’s investment strategy to build up China’s capabilities in artificial intelligence, robotics, aerospace and other niches, including semiconductors and 5G networks.

READ: The trouble with 'Made in China', a commentary

It is hard to estimate the number of international firms in this space. Therefore, while a decoupling of American and Chinese interests in these areas will deal a major blow to Beijing’s economic and geopolitical interests, it will have similar effects on global value chains and ecosystems.

As to the degree of decoupling, a range of different outcomes could play out and businesses need to start mapping out scenarios ranging from mild to extreme decoupling.

For all outcomes, firms are going to have to learn to live with increased uncertainty as they contemplate the extent to which they will have to decouple and where they will turn to for new markets, partnerships and livelihoods.

US SANCTIONS AND TECHNOLOGY CONTROLS

The amount of collateral damage caused by US sanctions and blocked technology licenses cannot be overstated. When the US government threatened China telecoms manufacturer ZTE with a seven-year ban on access to US tech suppliers, for example, US companies such as Qualcomm, Android Software, Google, Microsoft — and their legions of smaller suppliers and subcontractors — were all adversely impacted.

It turns out that American firms account for more than 30 per cent of the components and technology that go into a “Chinese” ZTE phone.

Washington eventually backed off from its threats, which saved ZTE from likely collapse. But this begs the question: If Sino-US relations continue to deteriorate, is Washington willing to pursue ZTE enforcement style strategies to decouple US tech firms from other Chinese companies?

So far, yes.

The Trump administration has just slapped technology export restrictions on Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Company, another state-funded tech firm.

Citing national security risks and allegations of a well-orchestrated Chinese campaign to steal trade secrets from Micron, the American firm that makes DRAM technology, US authorities have placed Fujian Jinhua on a restricted entity list.

For Fujian Jinhua, the spigot to US tech has been turned off, but even non-US firms that incorporate American technology in their own products are affected, as they are also banned from doing business with this Chinese company.

The penalties for violating these sanctions are harsh: Huge monetary fines, revocation of US operating licenses, blocked access to US dollar-denominated transactions in the international banking system, and even jail time for company executives.

How should a tech firm factor in these threats as it tries to hedge its risks in its business dealing with China? Does it follow a risk-averse strategy and pre-emptively decouple or should it live dangerously and wait for the next round of sanctions from Washington?

READ: Yes, it's time to end the US-China trade war, a commentary

THE MASSIVE SCALE OF DISENTANGLEMENT

According to Barry Jaruzelski, a principle in PWC’s Global Strategy group, 80 per cent of the corporate research and development (R&D) money spent in China in 2017 came from non-Chinese multinationals.

These R&D ecosystems are linked to extensive collaborative networks of businesses, universities and talent pools, all of which, in turn, are supported by a myriad service providers such as advisory firms, financial institutions and IT companies.

The scale of China’s local R&D and product development market is massive. McKinsey, the global consultancy, estimates that the total demand for new components generated by local R&D and product development centres in China will be valued at US$500 billion, by 2020.

But much of this tech still passes through global value chains. Sanford Bernstein, a research company, reports that China imported around US$160 billion worth of integrated circuit-related technology in 2016, making semiconductors its number one import—surpassing even oil imports.

READ: As summits approach, winds of trade war hit region, a commentary

Every area of Beijing’s Made in China 2025 technology master plan is dependent on foreign-owned integrated circuit technology, with much of it coming from five American manufacturers: AMD, Intel, Micron, Nvidia and Qualcomm.

Not surprisingly, key groups in the US semiconductor industry are worried about the collateral damage from an increase in sanctions and have been lobbying the Trump administration to exercise restraint — even while they have been complaining about Beijing’s efforts to promote its own tech champions.

In the short term, the ideal scenario would be to obtain a similar outcome to the ZTE case, where Washington decided not to enforce a technology ban, while, simultaneously, a constructive dialogue between Washington and Beijing could begin to work out some sort of modus vivendi.

Simple logic would dictate that leadership on both sides should engage and try to avoid the carnage of an extreme decoupling.

INCREASED DECOUPLING

But the clock is winding down. Many observers of Sino-US relations have concluded that US Vice President Mike Pence’s recent speech at the Hudson Institute — where he proclaimed that the US will not back down From Beijing’s aggression — was the equivalent of the Iron Curtain speech made by Winston Churchill in 1946, which marked the beginning of the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, anti-China sentiment in the US Congress, across both political parties, is at an all-time high. Democratic gains in the 2018 mid-term elections, in US House of Representatives, will not change this.

Thus, Congress will remain largely silent while a small group of economic nationalists like Peter Navarro, adviser to President Trump on trade matters, and Wilbur Ross, the Secretary of Commerce, exert undue influence over US trade policy.

Increased US-China decoupling in the tech sector, therefore, is a real and increasingly likely scenario. While the full extent of a decoupling is hard to predict, tech firms, from the world’s largest to the newest start-ups, need to adopt new ways to manage this risk.

Alex Capri is Visiting Senior Fellow with the Department of Analytics & Operations at NUS Business School.