Gaia Series 103: Trump's tariffs and Japan's manufacturing industry

Japan’s auto industry faces Trump’s tariffs with survival strategies, shifting supply chains and fostering community pride in manufacturing.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Japanese manufacturers face Trump’s tariffs with strategies for survival and resilience in production.

The latest episode of Japan Hour examines how Japanese manufacturers are coping with the impact of Donald Trump’s tariff policies, which have thrown global supply chains into turmoil.

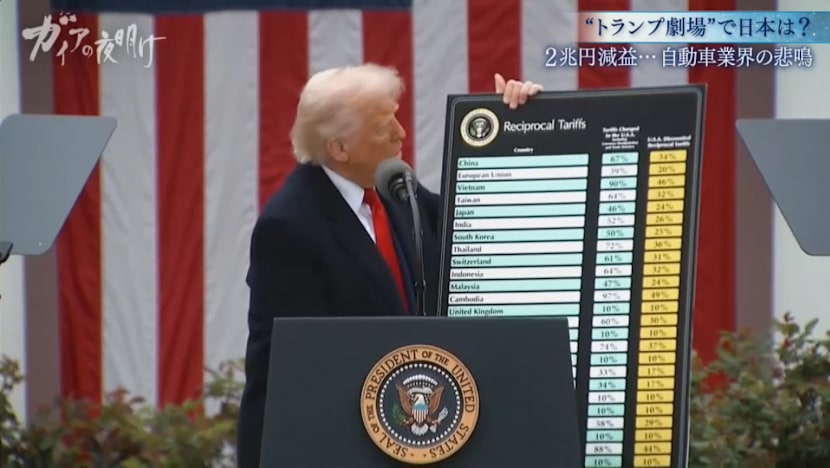

At the White House this year in April, Trump declared: “If you want your tariff rate to be zero, then you build your product right here in America because there is no tariff.” His sudden announcement of tariffs on all imports sends shockwaves through Japanese carmakers, long reliant on the US as a key market. Subaru president Atsushi Osaki warns: “The US is an extremely important market, and these tariffs will have a significant, grave impact.” Mazda president Katsuhiro Moro adds: “We must swiftly shift into survival mode.” Industry forecasts show that across seven major carmakers, profits could fall by two trillion yen (S$18.5 billion) a year.

In Ohio, the pressure is felt acutely at Daido Metal USA, which produces bearings, small but vital engine components that account for about 40 per cent of the global market. Company president Yasuhiro Okura admits: “Yes, there is no day or night now.” Already absorbing a 10 per cent reciprocal tariff, Daido faces the threat of duties rising to 24 per cent if negotiations fail. “If it goes up to 24 per cent, the impact will be enormous,” Mr Okura says, noting the company’s dependence on supplying Toyota, Nissan, Honda, GM and Ford.

Komatsu, the construction machinery maker, also faces serious risks. At Kobe Port, excavators are hurriedly shipped to the US before a 90-day grace period ends. Hiroaki Takahashi, who leads Komatsu’s tariff countermeasures team, describes the internal discussions: “We have loud debates like, ‘Where do we make and ship the body? That part is going from China to the US. So what should we do?’” Komatsu forecasts operating profit to fall by 94.3 billion yen this fiscal year, with net profit expected to drop by 30 per cent compared with last year.

The company explores shifting production back to Japan, turning to partners such as Tagami EX, which has supplied bulldozer parts for decades. Its president, Yoshihiro Tagami, agrees to help: “Please see this as a business opportunity. We intend to take on the whole order. We will commit fully to this deal.” Yet just days later, Trump doubles tariffs on imported steel and aluminium to 50 per cent, underscoring the uncertainty companies face.

The episode also shifts to the US Rust Belt, where the human consequences of globalisation are visible. In Middletown, Ohio, retired steelworker Michael Bailey recalls better days: “I put my kids through college and retired. I have health insurance and a pension. Not bad, right?” Others at a food aid centre express desperation. One father, holding groceries beside his daughter, explains: “I’m trying to work my butt off just so she can go to college and you know, be someone in life.” He adds, “Help us, we’re hungry. We’re hungry.”

The programme shows how Trump’s tariffs resonate in such communities. Vice President JD Vance, a Middletown native and author of Hillbilly Elegy, campaigned on a promise to bring manufacturing back. At a Memorial Day parade, one resident says: “I think it’s cool that one of our own is in the White House. We’re rooting for him.”

In Japan, small suppliers such as Toyoda Giken in Gunma Prefecture are bracing for impact. Its president, Nobuyuki Toyoda, estimates that a 24 per cent tariff would reduce profits by 30 per cent. “Tariffs are a real headache. The uncertainty is deeply worrying,” he says. Orders from the US have doubled suddenly, but his son and executive vice president, Shinya Toyoda, is cautious: “When orders rise sharply, they can crash just as sharply after, so it’s not a reason to celebrate.”

The Toyoda family’s history underlines their resilience. During the 1995 Japan-US auto talks, the company nearly went bankrupt. Mr Toyoda recalls how clients tried to shift production to the US but failed due to quality problems, leading to increased orders for the Japanese factory. Today, Shinya leads a project to develop new LED heat sink parts with lower costs. “We’re in a crisis now, but there’s always opportunity. We just have to find it,” he tells employees at a gathering.

The episode ends with Komatsu’s new president, Takuya Imayoshi, considering the long-term choices facing Japanese firms. “If all production, including parts, were to be done in the US, I think it would be very difficult,” he says, stressing that key components such as engines will continue to be produced in Japan. He avoids political comment but concludes: “Our focus is on how we can continue to provide the same or better products and services to our customers and markets.”

What emerges is a portrait of an industry under siege but unwilling to yield. The programme underlines this determination with a message that echoes throughout: Japanese manufacturers refuse to be beaten.