The Big Read: Cyberbullying is more rampant and damaging to young lives than we think. It's time to take it seriously

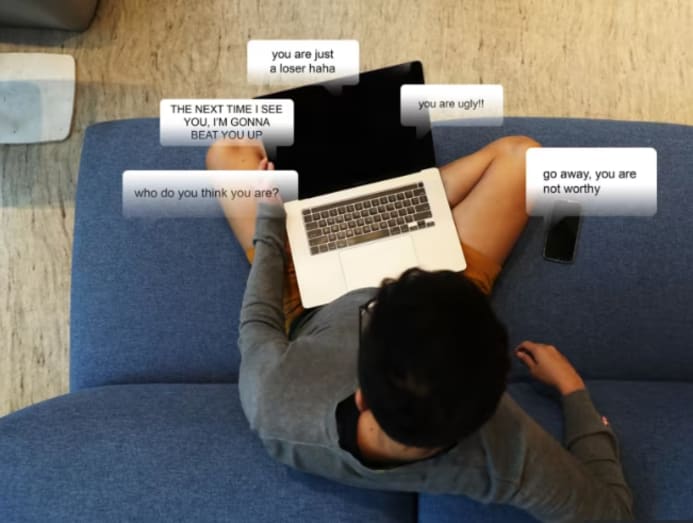

With more children getting hold of digital devices at an ever younger age, the risk of cyberbullying will only grow in the coming years, experts reiterated. (Illustration: TODAY/Anam Musta'ein)

- As the lives of children and youths become more intertwined with smart devices and the Internet, research suggests that there is a growing risk of them being cyberbullied

- Separate studies in the United States and Singapore have found that almost half of the respondents in these countries have experienced some form of cyberbullying or online harm

- Victims of cyberbullying said that beyond the immediate hurt, it has had a long-lasting impact on their mental health due to the effect on their formative years

- The Ministry of Education said schools have taken steps to address the situation, with the number of reported cyberbullying incidents remaining “low and stable over the past five years"

- Nevertheless, the problem could be underreported as many youths tend to suffer in silence. Experts say that victims should turn to a trusted adult for help, while parents and educators need to take more preemptive measures to protect their children

SINGAPORE: Having distanced herself from a close female friend after a falling out, Ms Erin Seah, then 15, thought that she could move on.

Then one night, her phone buzzed - a mutual friend sent a slew of screenshots from an Instagram post where she was called, among other things, attention-seeking and dumb.

Ms Seah recalled the horror of learning about the post which had vulgarities and veiled threats of violence targeted towards her. Her friend-turned-bully wrote: “I swear … I WILL break my no detention record in school since Secondary 1 for the sake of just one punch to give it to ya.”

While her name was not mentioned in the post, a comment confirmed her doubts. “You’re talking about E**n, right,” read the comment in a screenshot Ms Seah showed TODAY.

What started the torrent of online abuse? It was over the same mutual friend that had sent her the screenshots - Ms Seah had rejected his feelings, and her bully took it personally.

“She thought I was taking advantage of him for not reciprocating his feelings, and that I was attention-seeking,” Ms Seah recalled of her bully.

Although about six years have passed since the cyberbullying took place, Ms Seah, now 21, told TODAY that she has yet to put the traumatic episode fully behind her.

“I struggle to make friends because I’m more self-conscious and am constantly wondering what they think of me. And while I was confident and outgoing before, I really second-guess myself more often,” said Ms Seah, who will be starting her first year at a local university soon.

“I’m still struggling to figure out who I am, beyond the people-pleasing to avoid being bullied again.”

Her bad experience is not an anomaly for children and teens around the globe.

A study released last month by the Pew Research Center found that nearly half (46 per cent) of teens aged 13 to 17 in the United States have experienced cyberbullying.

The most common form of cyberbullying they faced was offensive name-calling (32 per cent), followed by false rumours (22 per cent) and receiving unwarranted explicit images (17 per cent).

A study last year in Singapore by public-private tie-up Sunlight Alliance for Action (AfA) showed similar findings: Nearly half of the 1,000 respondents - Singaporeans and permanent residents aged above 15 - had experienced some form of online harm such as being stalked online and cyberbullied.

However, about 43 per cent of them said they would not take action because they believe it would not make a difference.

For Ms Seah, she also did not do anything about the cyberbullying - until her mother found out about it.

While the then-teenager knew that her ex-friend had been one of the cyberbullies, the other comments on the Instagram post were made using accounts that she could not identify. Coupled with bullying physically in school - such as threats of violence and mean comments - and the online death threats, Ms Seah started ostracising herself from others for her safety.

“I would go to the toilet when there wasn’t a teacher in class, and immediately run back home when the bell rang so that I couldn’t be attacked,” she said. The fears led to her skipping school for a week with the excuse of not feeling well.

“It was uncharacteristic of me (to skip school), but the bullying took a toll on me. My mum recognised that something was wrong, so she pushed for an answer and was obviously upset.”

Her mother went to the school to make a complaint but was stopped from making a police report by Ms Seah and her teachers. However, the bullying - both online and in the real world - continued and it only ended when Ms Seah completed secondary school about a year later.

Like other victims of cyberbullying who spoke to TODAY, Ms Seah still struggles with its effects.

The lingering aftermath is something experts said requires a more in-depth examination in Singapore, given that cyberbullying can be more vicious than its traditional forms: It is often archived on the Internet, and has a 24/7 presence in victims’ lives.

Professor of Communication and Technology at the Singapore Management University (SMU) Lim Sun Sun said: “One of the most haunting things a victim has said to me during my research is that ‘at least the bullying will stop if it's face-to-face. But with online bullying, it just continues and continues because I take my phone home with me’.”

Beyond that, she noted that for youths who are curious about how people perceive them, cyberbullying can have an enduring impact as archives of their bullies’ comments can be seen as feedback that is accessible anytime.

Bullies also tend to extend traditional bullying into the online realm, added Prof Lim, who is also the vice president of partnerships and engagement at SMU. For example, mean comments said in person could also be said online.

“With many children being online and their network of friends being replicated online, the peer dynamics will also filter from offline to online naturally,” she said.

With more children getting hold of digital devices at an ever younger age, the risk of cyberbullying will only grow in the coming years, experts reiterated.

MOE TAKES "SERIOUS VIEW OF ANY FORM OF BULLYING"

In response to TODAY’s queries, the Ministry of Education (MOE) said that the number of reported cyberbullying incidents has “remained low and stable over the past five years”. It did not give any figures.

The ministry said it "takes a serious view of any form of bullying, including cyberbullying", and that schools have in place various measures to address this issue.

For example, there is the Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) curriculum, which students go through from Primary 1.

"Given the increased use of digital devices today, there is greater emphasis on cyberwellness in the CCE curriculum, where students learn to be discerning, safe, and responsible users of technology,” said MOE.

“Students are also taught how to develop a positive online presence, and to be a positive peer influence.”

Similarly, polytechnics and the Institute of Technical Education had strengthened their cyberwellness curricular in 2021 to enhance teaching of digital well-being and online ethics.

MOE added that students are also taught how to report cyberbullying and other serious incidents using safe channels. Schools have students appointed as peer support leaders to encourage safe and positive spaces both online and offline, and to also alert their teachers if necessary.

When schools receive a report of cyberbullying, trained staff will “promptly investigate the allegations and provide counselling support where needed”, the ministry said.

Schools also mete out appropriate disciplinary actions against perpetrators, and may make referrals to social and community agencies for specialised support if required.

“Our schools take an educative and restorative approach to help students involved in bullying cases to learn from the incident and reconcile with each other," said MOE. "Beyond this, schools also work closely with parents of perpetrators to help them understand the impact of their actions and take responsibility to restore the relationships with whom they have hurt.”

VICTIMS HIDE CYBERBULLYING FROM PARENTS, TEACHERS

In 2020, Mr Ryan Ong, 24, founded The Catalyst Collective, a mental health support group which connects people through board games and role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons. He was a victim of bullying himself during secondary school.

In late October last year, he gave a presentation at a university in Malaysia on how he overcame bullying. While preparing for it, he logged into his Facebook account to look for the hurtful remarks left by his then-secondary schoolmates.

Reading those remarks again made him flinch. “It may have been more than 10 years, but it was a traumatic experience,” said Mr Ong,

“I don’t remember if the ostracising in class or the cyberbullying started first, but nonetheless, my depression and anxiety worsened during this period, though I was not formally diagnosed then, and I developed post-traumatic stress disorder.”

He was called attention-seeking when his classmates learnt that he was suicidal, with comments asking him to end his life, among other things. His grades worsened, as a result of the bullying and isolation.

With no one to support him, Mr Ong turned to video games as an escape, and it was there he found a group of friends who supported him.

“I skipped school a lot, as my teachers did nothing and my mental health worsened. The school suggested my parents take control of my devices (to improve my grades), and my parents thought it was the right thing to do. However, that only alienated me further," he said, adding that his parents did not acknowledge the bullying that took place.

Other victims told TODAY that they feared telling their parents about the cyberbullying as they did not want their mobile devices confiscated. Some who eventually did added that their parents told them to simply turn off their devices, and the lack of action made the youngsters feel more helpless.

Since parental response can also worsen a situation, experts advise that they stay calm and also consult their children about the subsequent action to be taken.

When it comes to older children, Dr Anuradha Rao, the founder of CyberCognizanz which promotes awareness about cyberwellness, said: “Nowadays, it's (common) for parents to overreact towards a lot of things, even bullying in minor forms. Sometimes, children need to be trusted to navigate on their own, and it also can be an opportunity for them to be resilient.

“It is only when they can’t resolve the issue on their own, then parents should step in.”

This could be when a child’s emotional well-being is impacted, and they exhibit certain negative behaviours, such as a reluctance to open their social media and messaging applications or skipping school.

Dr Anuradha added that simply removing a mobile device from a victim of cyberbullying can worsen the situation, as the lives of children and teens are intertwined in both the offline and online worlds. Depriving them of access to the online world may make them feel further isolated.

For Amanda (not her real name), her mother’s overreaction worsened the situation with her cyberbully in primary school.

Having discovered that a group of friends had created a private group chat to speak behind her back and throw vulgarities at her, Amanda informed her teachers the same week, resulting in her bullies being scolded and having their phones confiscated.

After her mother learnt from Amanda about what happened, she called one of the bullies directly to scold her.

“The bully told her friends about what I supposedly did to get my mum to scold her. Because of it, everyone (in class) viewed the bully as a victim instead,” recalled the now 22-year-old.

While she was unaware if her classmates continued speaking ill of her in their private chat group after her teacher took disciplinary action, she said the face-to-face bullying persisted in class.

“Time heals, but whenever I recall all these instances (of bullying) … I still feel the same way as I did (then),” she said.

The cyberbullying problem extends beyond a youngster’s known circle, with SMU’s Prof Lim noting that different online platforms may bring a child into contact with anonymous tormentors.

For example, online games may expose children to trash-talking and other vulgarities from strangers with little emotional connection to them, while public YouTube and TikTok videos may be viewed by strangers who can leave mean comments without care if parents do not turn on the privacy settings in these platforms.

While any form of bullying can inflict trauma on its victims, the impact can be extremely harmful to youths since they are less equipped to handle such emotions, said Mr Asher Low, founder of non-profit Limitless, a non-profit organisation that provides counselling for youth.

“The Internet is a huge part of the lives of the youth who almost live on the Internet,” he said.

“So when that online space becomes unsafe due to cyberbullying - yet it is a requirement to continue being in these online spaces because all their friends, activities, things they like to do are there - it does impact younger people more.”

While Limitless has not seen an increase in cyberbullying victims in recent years, the impact is still something that needs to be addressed, Mr Low said.

Victims may end up grappling with loneliness and poor social relationships, as well as having difficulties concentrating in class, lowered self-esteem and depression, said Ms Ann Hui Peng, group lead of children development and director of student service at Singapore Children’s Society.

She added that some children may start to self-harm, avoid going to school and see a drop in their academic results.

In the last two years, the Singapore Children’s Society Tinkle Friend helpline for primary-school children saw the number of calls and online chats related to bullying increase from 163 to 217, said Ms Ann. The society does not differentiate between cyberbullying and other forms of bullying.

WHAT PARENTS CAN DO

For children who are cyberbullied, Ms Ann said parents should teach them to follow four steps:

- Stop: Do not respond to the cyberbully, or comment or share the post

- Block: Prevent the cyberbully from contacting the victim by blocking

- Save: Screenshot a copy of the message or post as evidence

- Tell: Report the cyberbullying incident to a trusted adult

Beyond taking action when children are cyberbullied, cybersecurity experts said that parents need to better educate their children on online safety as a preemptive measure.

A Google survey of 500 Singaporean parents with children between the ages of five and 17 last September found that three in 10 parents did not feel that their child is well-informed about online safety issues.

It also found that the average age for a child to own a mobile phone is 10 years old, but the average age they are spoken to about online safety is around 13 years old.

Dr Anuradha of CyberCognizanz said that in general, parents should not give their children Internet access until they are older and able to better discern right from wrong, reducing the risk of them being exposed to online harms.

Ms Nina Bual, co-founder of cyber education company Cyberlite Books, added that it is crucial for parents to educate their children from young.

“Parents have to give their children the tools and the thinking skills to know what to do when a cyberbullying scenario occurs. Because the parent will often never be in the room when it occurs, so children should be able to say, ‘Okay, I am empowered, and I know what to do.’”

When it comes to protecting children from cyberbullying by strangers, Ms Bual emphasised the importance of enabling privacy settings. “If you wouldn’t let a stranger into your child’s bedroom, why would you let them into your child’s phone?”

For example, parents can adjust the settings on social media platforms such as TikTok to ensure their children do not interact with strangers. This also applies to games like Roblox, a free-to-play game popular among young children but has violent and sexual user-generated content accessible if parental controls are switched off.

Aside from that, being involved in their children’s Internet usage can help parents with monitoring, and allow them to set a good example of proper Internet etiquette.

Ms Bual said: “It’s cheesy, but I believe that a family that scrolls together, stays together. If you spend time with your child, play the same games as them or ask what video they are watching, they know that you are invested in them and it opens up an opportunity for conversation about what they should and should not be doing.”

But what if parents realise their child is a cyberbully?

Like traditional forms of bullying, it is important to get to the root cause of the behaviour, said experts. Parents should also explain to their children the impact of their bullying on themselves and their victims.

Singapore Children’s Society Ms Ann said: “Bullying not only affects victims but the bullies as well. There has been much research indicating that if left unsupported, some bullies may engage in aggressive behaviours in adulthood, have impaired social skills and relationships, or even experience depression and suicide.”

Added Prof Lim of SMU: “With cyberbullying, sometimes bullies think that it is not going to have any physical kind of damage as it is just an image or a few words on the Internet. So it is important to elicit a sense of empathy in the bully to explain that their actions can inflict lasting damage on the victim.”

For Ms Seah, the scars of being cyberbullied in her teen years have yet to fade away. However, despite the bullying on social media, such platforms are now helping her to recover from the trauma.

“On TikTok, there may be a lot of negative comments, but there is also a platform and community of victims who speak up about their experiences (being cyberbullied),” she said.

“Knowing that we are all not alone helps with the healing process.”

WHERE TO GET HELP AND SUPPORT

Several hotlines for victims of cyberbullying are available. These include:

- Tinkle Friend helpline for children aged 7 to 12 at 1800 2744 788, or their online chat at www.tinklefriend.sg

- Coalition Against Bullying for Children and Youth's consultation service at www.cabcy.org.sg/e-consultation

- Touch Cyber Wellness's TOUCHline at 1800 377 2252

- Help123 helpline at 1800 6123 123

- Victims of cyberbullying can also seek help from the newly opened SheCares@SCWO, by calling 8001 01 4616 or texting 6571 4400. The one-stop support centre is jointly run by non-profit SG Her Empowerment and the Singapore Council of Women’s Organisation

This story was originally published in TODAY.