CNA Explains: When do negative comments or reviews cross the defamation line?

Is it still defamation if a post is private? What if it’s just an opinion that the products or services are bad?

File photo of a customer rating their experience at a restaurant online. (Photo: iStock)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: In a judgment made available on Tuesday (Sep 9), a housewife was ordered to pay S$25,000 (US$19,500) in damages for defaming a company because she made disparaging comments about the produce it sold.

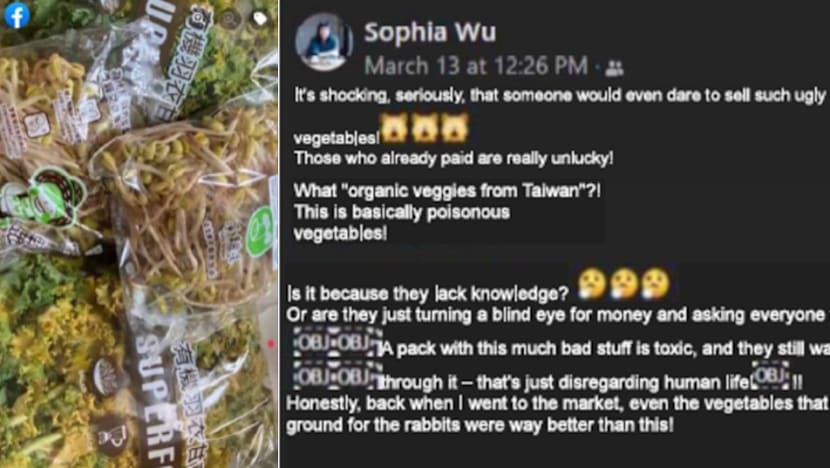

D'Season, a company that specialises in the import, distribution, sale and wholesale of goods and produce from Taiwan, successfully sued Ms Sophia Wu Chao Wen over a post she made on her Facebook page on Mar 13, 2022.

She wrote: "It's shocking, seriously, that someone would even dare to sell such ugly vegetables! Those who already paid are really unlucky! What 'organic veggies from Taiwan'?! This is basically poisonous vegetables! Is it because they lack knowledge? Or are they just turning a blind eye for money and asking everyone to pick out the good ones? A pack with this much bad stuff is toxic, and they still want customers to pick through it – that's just disregarding human life!! Honestly, back when I went to the market, even the vegetables that the vendor tossed on the ground for the rabbits were way better than this!"

When is it considered defamation?

Several conditions have to be met, lawyers said.

If the statement is untrue, lowered the business’ standing in society, caused it to be shunned or avoided, or exposed it to hatred, contempt or ridicule, it could be considered defamatory, said deputy managing director of Invictus Law Darren Tan.

For example, in the post about D’Season, Ms Wu had claimed that the vegetables were poisonous and toxic, which implied that the business sold toxic or poisonous vegetables, cheating customers and misrepresenting that their produce was organic, he noted.

But this was untrue and Ms Wu’s claims had no factual basis, said Mr Tan.

He also noted that Ms Wu did not name the company in her post, but had alluded to a previous incident related to it when someone asked where the vegetables were from.

Defamation law provides for innuendo, he noted. "Innuendo means that even if you didn’t name this particular company that you’re defaming, but from the context, people can ascertain who the company is."

In another case that concluded in 2020, the Fineline group of interior design companies successfully sued a couple who engaged them to renovate their condominium. The couple complained about delays and defects in the work and took to Google Reviews and Hometrust, an interior design e-marketplace, to voice their unhappiness.

The group eventually took legal action against the couple, saying it had been wrongly accused of being “unreliable, negligent, unprofessional and wholly incompetent” and had suffered losses.

It initially lost the defamation suit, but succeeded in its High Court appeal of the verdict. The court eventually ruled that the online statements in question were indeed defamatory, ordering the couple to pay costs to Fineline.

A statement that results in the business being tarnished would be considered defamatory, said Mr P Sivakumar, a director at BR Law Corporation.

“Statements that are going to create discomfort with the reader about the business - that would be a good rule of thumb as to what would be a defamatory statement,” he added.

The statement also has to refer to a specific business or person, said Mr Sivakumar.

For example, if an individual posted “all the hawkers in Singapore sell bad food” online, no single hawker would be able to sue for defamation, he added.

The defamatory statement must also be published. Even if an individual publishes negative comments on a private social media page that only their friends have access to, it is considered a published statement, Mr Sivakumar stressed.

In another case from 2022, car workshop On Site Car Accessories.SG, sued a man who posted in three Facebook groups for car enthusiasts claiming that the workshop was seeking to charge him a fee for checking a car battery that was under warranty.

He eventually had to pay the workshop more than S$51,000 in damages and costs for defamation. He was also ordered to remove the defamatory statements, publish a written apology on the three Facebook groups and refrain from repeating the statements.

Can people still leave bad reviews?

Lawyers said that reviewers should be careful to leave comments based on facts. Proving what you said was true is one defence against defamation accusations, they said.

“If you leave a review about something that is factually correct, then you have an absolute defence and there’s nothing that business can do to challenge you because your statement is a statement of fact,” said Mr Sivakumar.

Even if a statement is potentially defamatory, it does not mean you cannot publish it, especially if it is true, he noted.

For example, if a customer was served a fish that was not fully cooked and later posted a review about how the fish was not cooked properly, the statement would make those who read the review feel uncomfortable about going to the restaurant, Mr Sivakumar illustrated.

“That is already entering the zone of it becoming defamatory. But the fact remains that the fish actually was half-cooked instead of fully cooked.”

If this customer had taken a photo of the fish or sent a message to one of their friends about the half-cooked fish at the time, this could be used to support their comments, he added.

For negative comments or reviews that are based on opinions, it could be argued that they are fair comments, said Mr Sivakumar.

For example, if a customer went to a restaurant and left a review saying that they thought the food did not taste good, it would be a matter of opinion, he added.

But if a customer never ate at the restaurant but left a review saying that the food tasted bad, that would be considered defamation since they never went there.

When there is public interest, the statements may also be considered fair comment. For example, there would be public interest in letting others know that certain companies are selling poisonous products, said Invictus Law’s Mr Tan.

If they feel compelled to write a review, online commenters should stick to facts or describe their own experience, he added.

"It may be fair comment if someone visited a business and found the place to be too dark for their liking," said Mr Tan.

"But it’s a different thing if the person claims that the place is dangerous for visitors because it’s too dark, but has never actually visited the place."

In the D’Season case, the woman made her Facebook post based on pictures that she obtained from someone else and asserted that the vegetables were "poisonous" and "toxic" without proof, said director at Fortress Law Corporation Mark Yeo.

To ensure that a review does not amount to defamation, individuals should avoid using extreme terms or “quickly casting aspersions” on the integrity of the business without proof, he said, adding that such reviews may not be comments that can be backed up by facts.

“Reviewers should also make reviews based on their personal experiences, rather than what they hear from others. They should also avoid making broad, sweeping statements,” said Mr Yeo.

What happens if a business decides to take legal action?

In the case of D’Season, the company sent Ms Wu a letter of demand in April 2022 asking her to remove the post and publish an apology.

Ms Wu said she deleted the post a few days later but did not apologise.

Lawyers CNA spoke to confirmed that they are seeing more cases of businesses taking action against negative reviewers. In some cases, some negative reviews come from individuals who are not even customers, they added.

If served with a letter of demand, Mr Sivakumar encouraged individuals to read it carefully and understand what the business wants them to do.

They should then go back and read their review or comments, and see if they can justify it, he added.

If the individual has evidence, they can write back to the lawyers with it and stand by what they said if it is true. Similarly, if they believe they made a fair comment, they can reply that their review or comments were based on their honest opinions.

In defamation cases, the general advice to those being sued is that unless they can justify their comments and the other party accepts this, they should not spend money taking the case to court and incurring legal charges, said Mr Sivakumar.

“It is always better to resolve such matters amicably, and there are many avenues open to resolving such matters amicably,” he said, adding that mediation is also an option.

Most defamation cases are settled out of court, said Mr Tan, adding that “it’s not worth really fighting it out in court.”

Sometimes, businesses do not want to take the legal route because it may make matters worse, he said, noting that some may choose to instead issue media statements over taking negative reviewers to court.

“Typically, what businesses want is for the post to be removed and maybe an apology.”