The Big Read: Pressures and temptations aplenty in sporting world, only a rare few can scale the peak and stay there

Already pursuing a path less travelled, sportspeople often have to make sacrifices in their personal lives. And the scrutiny is even worse for successful athletes, with the public quick to criticise their every move.

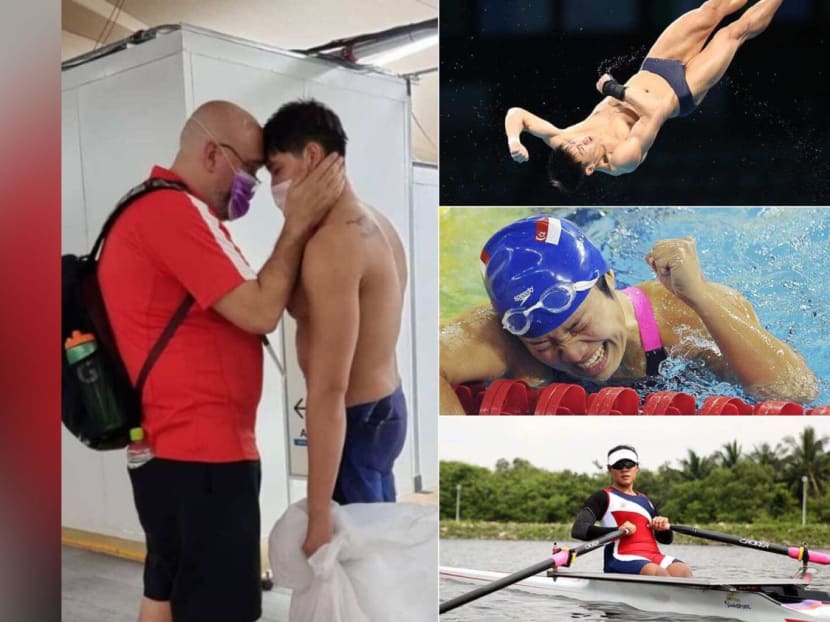

SINGAPORE: In the months after former national swimmer Tao Li sprinted her way to a fifth-place finish in the 100m butterfly event at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the expectations for her to deliver a medal at her next outing weighed on her mind.

She is still the first and only Singaporean female swimmer to make it into the finals of a swimming event at the Olympics thus far. And being only 18 at that time, there were hopes that she could achieve a medal in the 2012 London edition of the Games, when she had matured further as an athlete.

However, the 32-year-old told TODAY that the expectations and pressures of reaching the top became too much for her.

“Once you reach the top, many things can distract you, and then you’re not focusing as much anymore, and you don’t want to take that much pain anymore, you don’t want to train that hard anymore, and then things will just change, immediately," she said.

“If over the course of one year, you’re still out of the top eight (swimmers) in the world, then that’s it. You won’t just get back to where you should be anymore."

Sure enough, the years between the two Olympics were turbulent for her, with several coaching disruptions and a dip in form.

Though she improved her pool timings before the 2012 Games, it could only guarantee her a 10th place finish in the 100m butterfly, which did not earn her a spot in the finals.

But Tao is not one to wallow in pity or rue the missed opportunity, as she knows better than anyone else that the world of elite sports is a ruthless, unforgiving one, where failures abound and success is rare.

To her, what matters is that she tried her best.

“Everyone’s perspective is different ... some fans will say that national swimmers should try to break the world record, but the swimmer might think that this is their best (effort) already,” she said.

“Both parties are not wrong - the swimmer represents themselves, but the public wants some more, and that’s fair.”

While Tao, who now runs her own swimming academy, has made peace with the ups and downs of her sporting career, the same pressures that she faced continue to hound the current crop of active sportsmen and sportswomen in Singapore.

One example is national rower Joan Poh, who had to contend with her own perceived failure during the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, which was only held last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 31-year-old had been an inspirational figure - both locally and internationally - during the sporting extravaganza, having juggled her training for the Olympics with her job as a nurse at the height of the pandemic.

Poh said that given the upheaval caused by the pandemic, even qualifying and making it to the start line at the Olympics was “a feat on its own”.

During the Games, she was placed 28 out of 32 competitors in the women’s single sculls competition - which left her feeling discouraged.

“That is not winning, so I naturally came back and felt this sense that my outing to Tokyo was a failure,” she said.

It was only during the National Day Rally last year, when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong lauded Poh’s feat as embodying “the best of being Singaporean”, that she began to see her efforts in a different light.

“When the Prime Minister called what I was doing the Singapore spirit, and something we can celebrate, it actually lifted my spirit.

“At this point, we don’t celebrate hard work, we work so hard, but then (it’s as if) when we don’t have a medal, we don’t deserve celebration,” Poh said.

The various pressures faced by athletes - both in and out of the sporting arena - have come to the fore once again following the recent case of drug use by Olympic champion Joseph Schooling and national swimmer Amanda Lim.

The 27-year-old Schooling said in a public apology that he had given in to “a moment of weakness after going through a very tough period of my life”. The swimmer lost his father Colin, who had played a key role in his success, to cancer in November last year.

In her own apology, Lim, 29, said that her swimming career has been filled with “many ups and downs” over the past 10 years, and that she has “always strived to be better in and out of the pool”.

Former national athlete and swim legend Ang Peng Siong told TODAY earlier that the two swimmers’ case shows “how vulnerable an athlete can be when faced with life’s challenges and adversity”.

While some may argue that the pressures faced by Singapore’s national athletes are part and parcel of being in their chosen field, and it is up to them to find ways to cope with the stress, the fact remains that unlike most working adults, there are only so many ways a sportsperson can unwind and de-stress, veteran sportspeople told TODAY.

Other than the obvious no-nos such as the consumption of illegal substances, even simple pleasures like an alcoholic drink or a late-night supper may seem sacrilegious for these athletes, since they are also expected to keep their bodies in tip-top condition for their competitions.

And the scrutiny is even worse for athletes who have already gained some success in their sport, said the veteran athletes.

The pressure for them to stay on the straight and narrow, while continuing to produce sterling results, can often be too much for them to handle.

Amid the intense scrutiny faced by Schooling and Lim on a personal level, a bigger question has also arisen from the saga: Is Singapore capable of ever producing a serial world beater who can bring home multiple world titles - given that the creme de la creme in the sporting fraternity often find it hard to stay at the top, with the pressure to perform in the next major games only mounting in the wake of their initial achievements?

For instance, Schooling himself and 2021 Badminton World Champion Loh Kean Yew - Singapore's two most high-profile sportsmen in recent years - have yet to match their career-defining achievements or even come close since then.

THE PRESSURES ATHLETES FACE

In the world of elite sports, the pressures that athletes face creep in long before they dance under the lights. And on the big day, the competition itself is a stressful experience - but the pressure is often due to extrinsic factors.

Former national sailor and Asian Games gold medallist Benedict Tan said the fact that many of these top athletes receive public funding only adds to the pressure on competition day.

The Sport Excellence Scholarship (spexScholarship) by national sports governing body Sport Singapore, for example, provides financial support for high-performance athletes, as well as more opportunities to train and compete at major games, among other benefits.

“If (the athlete) is very conscientious, he will be under more pressure, as he feels that he has to perform well to justify the public funding,” said Dr Tan, 54, who was also Singapore’s chef de mission to the Tokyo Olympics.

“If you feel that your funding level is not commensurate with your performance … then there’s that added ‘guilty’ feeling which makes you want to perform harder, want to try harder and, of course, that puts more pressure on you.”

Agreeing, sports psychologists said that other than the pressure from public funding, there are also other expectations that ironically stem from the athletes' own support system - such as family and the sporting associations, due to the amount of resources that they have poured into the athletes’ development.

Dr Jay-Lee Nair, psychologist and practice owner of Mental Notes Singapore, said the underlying pressures that parents exert on their children comes at a young age.

“(Athletes) recognise that their parents are putting in considerable investment financially, spiritually, and it becomes heavy for them … They feel like they have to achieve these goals to not let their parents down.

“It is very common for young athletes to ineffectively process their performance, and they can fixate on it for a really long time, and it can really affect their performance going forward,” she added.

Dr Jay-Lee said that for athletes who feel such pressure, it is important for them to find an outlet to talk about how they feel immediately after a competition.

She suggested that athletes should go through a “debriefing process” after a competition is over, where they talk to either their parents, psychologist or coach about what they did or did not do well as they competed, and how they can improve.

“This is so that they can develop a much more productive reflection process at the end of every single competition … and not just focusing on the errors they made.”

And while most athletes who do not make it to the top of their sport remain relatively anonymous to the public, a whole new dimension of pressure sets in the moment they prove themselves on the world stage.

Take it from Schooling’s former coach, Sergio Lopez. Speaking to TODAY from the United States where he lives and coaches, the former head coach of Singapore’s national swimming team said that with success in the sporting arena comes the loss in an athlete’s “sense of self”.

“Winning an Olympic medal (means) you start being in the public image, and people start looking up to you as an example, and you lose ownership of who you are,” said the 54-year-old, who coached Schooling for five years leading up to his Olympic triumph, and again in 2020 to prepare for the Tokyo Games.

Lopez, who is presently the head coach of swimming and diving at Virginia Tech University, said that when Schooling first announced as a child that his dream was to beat American swim legend Michael Phelps, nobody other than his parents believed in him.

“After the Olympics, everybody came out of the woods saying ‘I was part of Joseph’s journey’, and people only want to see the positives of life … and to have a perfect life, a perfect family … That’s a lot of pressure for anybody,” he said.

Indeed, the public interest in Schooling’s life and fitness began to mount after his Olympic victory, with questions raised whenever he fell short in subsequent major games.

Even his physical appearance and weight became a talking point during the 2019 SEA Games.

Lopez said: “The biggest pressure is losing ownership of who you are, and having to live your life by everybody else’s expectations.”

UNIQUELY SINGAPORE PRESSURES

National athletes also face "Uniquely Singaporean" pressures, like having to keep one eye on their longer-term careers - be it in or outside of their sport.

And this is the key difference between athletes here and some of their foreign counterparts, said former national diver Jonathan Chan, 25.

His last competition as a national athlete was at the 2021 SEA Games in Vietnam which was held in May this year due to the pandemic.

“For a lot of other countries, (athletes’) priority will be sports, and then school is at the side. But for us, school is always the priority, and sports is more of a co-curricular activity,” said the 25-year-old Olympian, who also competed in the Tokyo Games.

For instance, he said it is not uncommon for student athletes to have their training cut down when they do not perform well at school.

Chan added that pursuing diving as a sport throughout his university years came at a huge opportunity cost.

“In university, the time that I spend doing my sport, other people spend doing internships, and if you go out there and get interviewed for a job, the company will obviously pick the people with more experience in the job, they won’t say ‘wow, this guy went to major games’.

“They always say do well in sports and you can go far, but it’s not (always) true,” said Chan.

Agreeing, former national sportsperson Nicholas Fang, who has represented Singapore in both fencing and triathlon, said the juggling of different priorities is more evident here as opposed to other countries, where “national athletes typically train full-time and are supported by the state”.

However, he said that this would help to “alleviate some pressure” as athletes can more easily see a path beyond the sport.

Fang said that he still felt the pressure from the sacrifices he was making to deliver on both the sports and career front.

“I felt added pressure in that all the sacrifices made to balance the different priorities would seem to be for nought if I wasn’t able to deliver sporting results,” said the 47-year-old.

The sport type also matters in determining the level of pressure one faces.

Ex-national badminton player Wong Shoon Keat said that for national badminton players, the sacrifices are often greater as compared to other sports, as most players play the game full-time.

“There is no choice, if you don’t play full-time, we cannot compete against the countries around us - Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand … because they are all playing full-time badminton,” said the 65-year-old, who won the nation’s first and only gold medal in badminton at the 1983 SEA Games held in Singapore.

“It is a big sacrifice, because you have to put away your studies, you cannot go to work early to focus on the sport and play full-time.”

Wong added that for many players who do choose this path, it is difficult to have quality training, as many of their sparring or doubles partners will usually leave the sport to pursue their long-term careers.

Singapore’s culture of prioritising academics over sport is also harmful to young athletes, said sports psychologists.

Dr Jay-Lee from Mental Notes Singapore said a lot of parents are invested in their children's’ sporting excellence not because they want their kids to become full-time sportspeople, but because it can help them gain entry to their preferred schools.

“Singapore is bursting with highly competitive developing athletes and their parents … They see success in sport at the youth level as a valuable addition to their resumes, either for top academic institutions, or as a vehicle for scholarship opportunities for university abroad,” she said.

She added that one accelerator for this trend is the Direct School Admission programme, where students can gain entry into top educational institutes based on their sporting merit.

This can have a negative outcome for children, who find themselves doing the sport for a very utilitarian purpose, other than pursuing it as a passion.

“The child might not feel like they have a lot of autonomy … Maybe they feel like it’s something that is forced upon them and if they don’t enjoy the sport, then I think it can be really quite difficult and have a lot of negative consequences,” said Dr Jay-Lee.

Agreeing, Poh said that the culture in Singapore, being a financial hub, is based on what monetary value sport can bring to the individual, investors and commercial brands sponsoring the athlete.

“The way we define success is not so much about the process or the journey, I think our pressure stems from not only wanting a gold medal … but it has to be a gold medal that can bring you money.

“Everything is tied to dollars and cents, and because of this kind of culture that we have, a lot of us don’t feel like we can do sports full-time … and instead need something to fall back on,” she said.

She added that for athletes who have already achieved success on the world stage, their inability to replicate their success in future games does not mean that (their achievements) are not worth celebrating.

“In sports what we want to encourage is not always the outcome, but more the spirit, the journey, the fight,” she said.

Despite the difficulties, former national athletes said that there are ways to balance expectations and put one's best foot forward, despite the sacrifices that have to be made to climb to - and remain at - the top.

Dr Tan said: “Is it constructive to tell myself that I am making a huge sacrifice and that I’m so pitiful?”

“I know that my life is different from others but I don’t pity myself … I see it the other way round, that I have a unique life, that very few people can get to live,” he added.

He also agreed with Poh that the public needs to have a deeper appreciation of the athletes' hard work and sacrifices, rather than solely the results they achieve.

However, the athletes themselves cannot be contented when they fall short, but should always be hungry to achieve better results. After all, many of them are backed by public funds and are naturally expected to deliver.

"The psychology behind winning and staying at the top and the satisfaction (in your effort) are two different things," said Dr Tan. "I'm not saying that if you win once, and you're a one-hit wonder, you should be satisfied with yourself."

Agreeing, former Singapore sprint king C Kunalan said being a national athlete entails putting aside many other opportunities, be it to progress in their careers, or in relationships, and this is something that has to be accepted.

“Every sportsman and woman who is hoping to achieve the highest level must realise that they need to make sacrifices,” said the 79-year-old.

“But for some it is not a sacrifice, but it is what they want and they feel happy doing this … They are passionate.”

IS THERE MORE PRESSURE NOW THAN BEFORE?

According to former national athletes, the pressures that elite sportsmen and sportswomen face have only increased over the years.

Kunalan said that the support that the athletes receive now is far greater than what he used to get, when he was competing in athletics in the 1960s and 1970s.

National athletes were granted two weeks of paid leave before any major games, such as the Southeast Asian Peninsular Games, as the SEA Games was known then, said the former school teacher.

During that period of intensive training, they would sometimes get free meals that came from public donations.

“A lot of the pressure would have been from the feeling that we had been given time off from work,” Kunalan said.

This pales in comparison to the larger amount of resources granted to national athletes now, under programmes such as the spexScholarship.

“I think definitely there will be more pressure on the current athletes, especially those at the highest level,” Kunalan said.

Dr Tan said that social media is also playing an increasingly bigger role in athletes’ lives.

“The athlete cannot block social media off totally, because that’s how he builds his fanbase … So they cannot run away, they have to engage social media because that’s part of being an athlete.”

He added that in general, “sponsorship stakes” are also higher now, which will also add more pressure to the athletes.

At the same time, due to the increased commercialisation of sports, there are generally more competitions and events now as sponsors seek to “pack the calendar”.

This arrangement may suit larger countries fine, as they have a larger group of world-class athletes who can take turns to compete in various competitions.

However, for Singapore, there are only a few athletes who are able to compete at the highest level, and so they have no choice but to go for most of these competitions to fly the nation’s flag.

Wong, who now is a badminton coach at the schools’ level, said this is the case for world champion Loh.

The 25-year-old has to go for back-to-back badminton tournaments “because we don’t have any players who can take over his place, while other countries have standby good players".

“So we always depend on Kean Yew … and he becomes very fatigued and very tired,” Wong said.

MANAGING TEMPTATIONS WELL

Veteran athletes said that no matter what the era, there's always the proverbial forbidden fruit somewhere to tempt or distract sportsmen and sportswomen from performing well.

These can range from gambling, alcohol and even drugs. Even innocuous deeds to the common man, like playing computer games, spending late nights with friends or a visit to a fast-food restaurant, can be seen as taboo.

Dr Tan said he does not think there are more temptations now, in the form of vices or distractions, than there were in the past; only their nature has changed.

During his youth, the “distraction” was video games.

While too many such distractions are bad, having no distractions is also not good for an athlete.

Dr Tan said that though he had abstained from playing any video games to focus on his training, his father was the one who actively encouraged him to play them.

“My father felt that I was so weird as a teenager who was not interested in computer games, that he forced me to play,” he said. “You want some normality … you cannot be totally ignorant.”

He added that he had applied this philosophy to his later years in the sport.

For instance, while he was training as a national athlete, he still went out with his friends for drinking sessions - except he would make compromises such as not consume any alcohol.

“When I don’t drink, my body still stays clean and optimal, but at the same time, I also want to gain more social skills,” he said. “While learning to be a better sailor, I also need to learn to be a better person, it’s not contradictory.”

However, sport psychologists said these compromises and ways of dealing with stress have to happen from a young age.

Chief sport and performance psychologist at SportPsych Consulting Edgar Tham said that to keep athletes away from dealing with their stress through unhealthy means, there needs to be a “proactive approach”.

With younger athletes, Mr Tham will often do a “mental screening” on them, such as asking them what their mental state is, and what stressors they face.

Should the athlete indicate any issues or show signs of stress, then the athletes will be supported by psychologists.

“The proactive approach is what (sporting bodies) don’t do enough, it’s like a ticking time bomb, once the stress goes beyond a certain level, athletes may take desperate measures to deal with it in their own way,” he said.

However, it is only human to err, and ultimately elite sportspeople cannot be expected to stay away from all of life’s temptations during the years they spend training and competing.

As Fang, the former national triathlete, put it, these sportspeople are in a high-pressure environment, and have fewer outlets than most to de-stress.

“For normal people, sporting activities can be a relief from the daily grind, but elite athletes don’t have this avenue, which might explain why they seek other ways to blow off steam and release stress,” he said.

For ex-national swimmer Tao, a common way for her to relieve the pressure of competition was to engage in retail therapy, and on rare occasions, she would go to a nightclub.

“Different people will have different ways to relieve their pressure … I think once or twice a year should be okay,” she said. “But when I was competing, I didn't smoke, and I didn't drink alcohol at all.”

Ultimately, said Schooling’s former coach Lopez, it is unrealistic to expect athletes to not want to do the things that normal people do.

Lopez, who won the bronze medal in the 1988 Olympics, returned to his country a hero, having been the first person born and raised in Spain to win an Olympic medal in swimming.

He went to a nightclub to celebrate the achievement, only to have some members of the public come up to him and criticise him for consuming alcohol.

“I’m not excusing any of that, but I think what people need to understand is that people are people and they go through a lot of things, and they feel very lonely and they make decisions that they shouldn’t.”

However, the sportspeople interviewed all agreed that a line has to be drawn with illegal substances, such as recreational or performance-enhancing drugs.

When athletes make such grave mistakes, they have to own up to them, because after all, they are still in the public eye and a role model to many.

“When you break the law, you have to be accountable, and you have to be responsible and you have to be honest with the mistakes that you make,” said Lopez.

CAN SINGAPORE PRODUCE SERIAL WORLD-BEATERS?

While the world celebrates serial winners - Roger Federer in tennis, Michael Phelps in swimming, Lionel Messi in football, and a select group of others who have gained sporting immortality - can we expect Singapore itself to produce more than one-hit wonders?

The nation has occasionally produced world beaters, such as Schooling, who went on to beat his idol Phelps en route to a gold medal in the 2016 Olympics, and badminton player Low, who outplayed then world number one Viktor Axelsen to clinch the world championship title last year.

However, such feats have yet to be repeated on the same scale for either of the two athletes, which begs the question: Is it fair for Singaporeans to expect a repeat of world-beating performances from our athletes?

The answer, according to veteran athletes, is “no”.

“People think that just because you are an Olympic champion, that you have to be an Olympic champion the next time,” said Lopez. “I’m sorry, but if it was that easy, everybody would do it.”

Explaining the difficulty behind such an endeavour, Dr Tan said there is a big difference between the time when an athlete is chasing for the top spot, and when he has reached there and is trying to maintain his dominance.

“It’s not easy to stay at world number one, because … it’s easier to be the one chasing,” he said. “Once you’re at the top and you’re the one being chased, your training strategy will have to change.”

Using a business analogy, Dr Tan pointed out that growing a small company often requires a very different set of skills from keeping a big company steady.

“The skills to stay at the top are much more complex … Most of the time, you practise chasing to reach the top, but how many get to practise staying at the top?”

So what makes serial world beaters tick? According to American science magazine Popular Science, the key difference lies in these athletes’ mental training and ability to stay focused.

For instance, these top athletes often train with distractions. When golf legend Tiger Woods was young, for example, his father would jingle keys or drop coins when he was in the middle of his golf swing.

For Phelps, American business news channel CNBC reported that the 23-time Olympic gold medallist would put his goals down on paper and frequently look them over, especially after a tough day.

He even has goals up to 20 years into the future jotted down, so that it helps him stay focused.

And according to British daily the Guardian, tennis legend Federer’s dominance on the court in a career spanning more than 20 years is due in part to his willingness to learn new playing styles and improve on his ground strokes constantly, despite already winning virtually every accolade in the sport.

Ultimately, it all boils down to the nation’s sporting culture, said Schooling’s former coach Lopez, echoing the sentiment expressed by other athletes interviewed.

He gave the example of when he was coaching swimming in Singapore between 2015 and 2016. While he saw many children with the potential to excel in the pool, they were never pushed by their parents to give their all to the sport.

“Kids didn’t show up to practise … because they had to study,” he said. “Instead of their parents telling them to come up to Coach Sergio to set up a plan, they would tell them (the kids) that they don’t have to come to practise.”

He added that Schooling’s path to success was in contrast to what he had observed in most young swimmers here.

A confluence of factors - Schooling having the potential to be a world champion, him daring to dream of beating Phelps one day, and most crucially, his parents believing fully in his dreams - was what led to an unlikely Olympic gold for Singapore, said Lopez.

Some psychologists and sportspeople pointed out despite the well-known constraints that Singaporean elite sportspeople have to grapple with, the pressures exerted on them - including in the form of public expectations - can actually spur them to even greater heights.

"It is up to an athlete, how he manages the pressure. If he manages it in a positive way, it becomes a good pressure that spurs him to work even harder," he said.

For example, Dr Tan said that even when he fared well in sailing regionally, he would often put additional pressure on himself to work harder, keeping in mind the fact that his performances still paled in comparison to the best the world had to offer.

"I would tell myself that I would have to work harder to justify my slot at the World Championships," he said. "That's what a conscientious person would do, he turns the pressure into something positive."

Whatever the future holds for Singapore’s elite sportspeople, Lopez felt that an Olympian like Schooling “doesn’t need to win another Olympic medal to be somebody that can change the country, because he has already changed it”.

“He has a lot of experience from living abroad, racing, and he can share that with the Singaporean youth, and it’s invaluable, you cannot pay for that with money.”

“So it’s really up to you guys, how you want to appreciate your own.”

This article was originally published in TODAY.

_1.jpg?itok=Pt4lopXb)