Stalled careers, limited earnings: How some young workers are getting stuck in delivery and ride-hailing jobs

While a short stint may not be harmful, experts caution that the longer young workers remain in platform jobs, the harder it may become for them to re-enter traditional employment, especially if they are not upskilling in parallel.

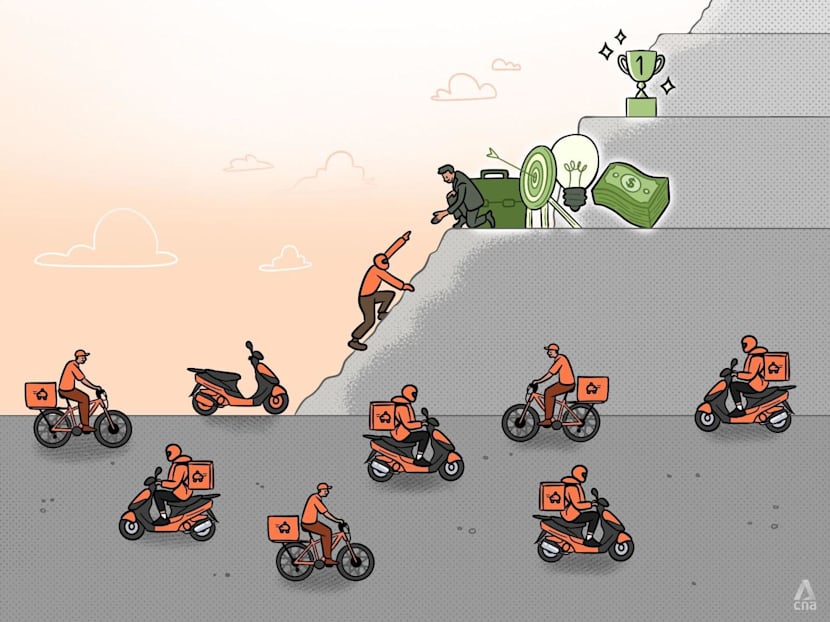

As more young people turn to platform work, concerns are growing about their long-term career mobility, especially for those who end up staying in such jobs longer than they intended. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

For the past five years, 29-year-old Ridhwan Danial has been spending up to 16 hours a day, six days a week navigating Singapore's roads as a delivery rider.

He has tried to pivot out of platform work, but his Higher Nitec qualification from the Institute of Technical Education (ITE) is in facility management, a field he no longer wishes to pursue.

His applications for non-platform roles have resulted in salary offers he said were significantly below both market average and what he currently earns – typically between S$6,000 (US$4,645) and S$7,000 monthly.

Mr Ridhwan told CNA TODAY that he does not want to do delivery work, but for now, it gives him the much-needed flexibility to further his studies.

He graduated this year from a two-year diploma programme in business management, and expects to continue delivery work while pursuing his university degree, also in business management, starting in April next year.

"If I worked other part-time jobs, I don't think I (would be able to) pay for my degree," he said. "Without this delivery job, I'll have nothing."

Platform work has grown increasingly popular as a career option both globally and in Singapore in recent years, driven by factors such as flexible schedules, greater autonomy, the ability to draw earnings daily or weekly rather than monthly, and the relatively low barriers to entry.

An advance release of the Ministry of Manpower's (MOM) 2025 labour force report on Nov 28 found that the number of resident platform workers – comprising those who provide ride-hail or delivery services – rose from 67,200 in 2024 to 71,600 in 2025.

The report also noted that of this number, the proportion of resident regular primary platform workers aged 39 and below edged up from 14.9 per cent in 2024 to 15.3 per cent in 2025.

As more young people turn to platform work, concerns are growing about the impact on their long-term career mobility – especially for those who remain in such jobs longer than intended and may not be fully prepared or informed about its longer-term consequences.

While many young workers are initially drawn to gig work for its perceived flexibility and autonomy, several eventually find themselves slogging away at a "hand-to-mouth job" with limited long-term prospects for career or income growth, noted researchers from the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Social Service Research Centre and the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) in 2023.

In their ongoing study on in-work poverty among the young, the researchers said that unlike other blue-collar roles that offer some progression and wage increments, platform work often lacks long-term sustainability, clear career pathways and social protection.

The study also found that given their qualifications and skill sets, many platform workers frequently experience horizontal rather than upward mobility – meaning they are typically able to find only roles with similar responsibilities and pay, rather than higher-ranking jobs with better wages.

Many ultimately return to gig work due to the struggles of moving to more traditional forms of employment, the study found.

Some of these concerns were raised earlier in Parliament in 2022 by former Members of Parliament including Mr Leon Perera and Mr Liang Eng Hwa.

In his response, Senior Minister of State Dr Koh Poh Koon listed career matching services by Workforce Singapore and NTUC's Employment and Employability Institute as well as other measures such as the Workfare Skills Support Scheme and SGUnited Jobs and Skills Package.

He added that the government "will continue to support platform workers to actively plan their careers and strengthen their employability, while respecting the preference of many to continue in platform work".

THE PULL OF PLATFORM WORK

The flexibility and autonomy of platform work remain major draw factors for many young workers, especially those juggling caregiving duties or further studies that require night classes.

Unlike roles in the retail or food and beverage (F&B) sectors, platform work does not require fixed shifts or supervisor approval for breaks. Working on weekends or public holidays – while often more lucrative – is also voluntary.

For Ms Azlyiana Mad Azmi, 29, delivery work allows her to juggle caring for her three children while earning an income during their schooling hours.

Ms Azlyiana began doing food delivery in 2020 – an arrangement that also helps her schedule appointments for her eldest child, who has autism.

While she hopes to have a more stable job or even start a small business of her own in the next five to 10 years, she expects to continue doing delivery work for now.

"Right now, delivery work feels more like a temporary phase while my children are still young," she added.

Another key appeal, riders like Ms Azlyiana said, is the payout structure. Many platforms allow riders to cash out their earnings daily or weekly, offering immediate liquidity that traditional entry-level jobs – typically paid monthly – do not.

The pulls of platform work are reinforced by push factors from more traditional forms of employment including academic barriers, mismatches in qualifications and a lack of autonomy in more conventional workplaces.

Ad-hoc work such as food delivery and private-hire driving does not require prior experience, allowing gig workers to earn a steady income while they pursue further studies or build skills to eventually move into a career of their choice.

A rider who wished to be known only as Mr Ng said that while he is currently taking courses in a variety of areas – including artificial intelligence, baking and cooking – spending the bulk of his days doing food delivery has allowed him to earn a decent salary over the last two years.

The 31-year-old previously held an operations role in the F&B industry, but left his full-time job for platform work, which offered him the prospect of earning more than he was making in operations.

Over the last two years, he has applied for other full-time roles in F&B, but eventually turned down at least four offers because they required him to work weekends and offered limited prospects for upward progression.

For now, being able to plan his own schedule gives Mr Ng time to work on branding ideas and logistics for the badminton racquet-stringing business he hopes to open in the near future.

However, he expects to continue delivery work even after launching his planned venture, to maintain his income while he builds up his customer base.

Others said they turned to platform work to escape rigid workplace rules and cultures.

Delivery rider Alvey Lim recalled a lack of autonomy during his earlier stint at a bubble tea shop, where he was discouraged from using his phone even when there were no customers.

Upon completing National Service (NS), the 20-year-old took up platform work full-time which felt liberating by comparison.

Although he now works very long hours – often from when shops open in the morning to past midnight – Mr Lim said being able to plan his own time and not having to report to an employer remain key draws for him.

At present, he has no plans to seek any forms of formal employment.

WHY PLATFORM WORK AFFECTS YOUNG PEOPLE MORE

These perceived benefits, labour experts said, continue to draw younger workers to gig platforms.

Dr Li Ding, an assistant professor in information technology and operations management at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) noted that while older generations tend to prioritise stability with a single employer, Gen Z workers are generally more comfortable with making frequent job transitions and "portfolio careers" – a model in which individuals strive for multiple income streams, roles and projects rather than relying on one job.

Labour economists also pointed to weak hiring sentiment as another possible factor nudging some younger Singaporeans towards platform work.

Third-quarter labour market figures released on Dec 11 by MOM showed job vacancies continuing to shrink in 2025, down to 69,200 in September from 76,900 in June.

A Singapore National Employers Federation survey released earlier this month found that nearly three in five employers plan to freeze headcount in 2026 amid uncertain business prospects. Of the 240 employers surveyed, 72 per cent said they faced uncertain business prospects this year, up from 58 per cent in 2024.

Dr Kelvin Seah, an associate professor of economics at NUS, said that with firms becoming more cautious about hiring, young and inexperienced workers may find it challenging to secure regular employment after graduation or completing NS.

The combination of these push-and-pull factors means many young workers now see platform work not only as a stopgap, but also as a realistic route to financial stability early in adulthood.

However, while taking up gig work can pose a challenge for anyone's long-term career mobility, young workers in particular are disproportionately affected by doing so early in their careers.

NTU's Dr Ding said that at one large Singapore food-delivery platform she studies, workers under 30 now make up about half (51 per cent) of all active couriers, including both full-time and part-time riders. Those in their mid-20s form the single largest age group.

The share of couriers aged under 25 has increased modestly over the past few years, while the proportion of those in their late 20s has remained relatively stable, said Dr Ding, whose research focuses on the gig economy.

Dr Mathew Mathews, principal research fellow at IPS and head of the IPS Social Lab, told CNA TODAY that young people who spend their early 20s in gig work may miss out on crucial workplace skills needed for long-term mobility.

"In many workplaces, there is structured training for newer workers to hone their technical skills beyond what they have picked up in school."

He added that those who begin their careers in platform work often have little opportunity to be socialised into informal workplace norms – such as collaborating with teammates, following supervisors' instructions, and meeting and reporting key performance indicators. Such individuals may find it more difficult to adapt to corporate working environments later on.

Even those who have had some prior experience in traditional employment before switching to platform work can still find it challenging to adapt when returning to non-platform settings, he said.

"This problem is further accentuated for platform workers who started to engage in this form of work at the get-go (of their working lives)."

THE 'STICKINESS' OF PLATFORM WORK

While a short stint in platform work may not be harmful, experts cautioned that the longer one remains, the harder it may become to re-enter traditional employment.

In a Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) study conducted between November 2024 and February 2025 on platform workers' occupational well-being, participants had cited key concerns about their long-term career prospects, such as "becoming obsolete in the broader workplace".

Some also reported a decline in their social skills, given the limited nature of social interactions in "task-based" platform work, said the study's principal investigator Dr Sheryl Chua.

"The connections they form with other platform workers are often superficial due to limited time to interact and engage in meaningful conversation," said Dr Chua, who is also deputy head of the Public Safety and Security Programme at SUSS.

This goes beyond soft skills such as collaboration, said Dr Ding: "Their professional networks remain almost entirely within the platform, with little exposure to employers or industries they want to transition into."

NUS' Dr Seah added that those who have spent extended periods of time in platform work also have less opportunity to build skills and experience sought by traditional employers, making them less attractive employment candidates.

Spending years in delivery work may also be perceived as a "sign of weak labour-market competitiveness or lack of 'fit' with office culture", said Dr Ding, particularly by employers who struggle to interpret workers' gig experience into conventional terms.

Employers may worry that such candidates lack exposure to teamwork, office systems or project-based work, she added – even if the individual has actually developed strong discipline and resilience through platform work.

The metrics of platform work, such as on-time delivery and cancellation rates, also have limited transferability and are not easily recognised or interpreted by traditional employers, said Dr Ding.

IPS' Dr Mathews noted that those with relevant skills were generally able to move into areas they were interested in when opportunities arose.

Mr Choo, 31, worked full-time as a delivery rider from 2019 to 2024 while completing his part-time degree in English. After graduating, Mr Choo continued delivering part-time while tutoring the subject. He now tutors full-time, as it offers better returns relative to hours worked.

For those with less formal credentials, however, their options tend to remain more limited.

Delivery rider Ms Azlyiana said: "With three boys (to care for), it's difficult to commit to a full-time job with fixed hours, (especially if it requires) qualifications or experience that I don't currently have."

Between her children and delivery work, she has almost no consistent time left in her weekly schedule for upskilling.

For such individuals, said Dr Mathews, platform work is still preferable because more conventional roles that offer comparable income given their skill sets often involve shift work – a struggle especially for those already shouldering burdens such as caregiving.

Time aside, the physically demanding nature of delivery work also means riders may not have the energy to attend courses outside of work hours, noted SUSS' Dr Chua.

Mr Asher Goh, a research associate at the NUS Social Service Research Centre, said that the challenge of returning to traditional forms of work becomes more pronounced for those who have spent a longer period in platform work – around five years or more.

He observed that many either do not hear back from employers or face repeated rejections, even when applying for roles in industries they previously worked in.

The impact is even greater for young people who lack prior experience and workplace skills, experts said.

For individuals wanting to transition into other fields but who have remained in platform work for five years or more, their resumes may show little recent experience relevant to their desired field or industry, said Mr Shamil Zainuddin, a PhD student at the University of California, San Diego, whose research focuses on the gig economy.

Meanwhile, their peers with similar qualifications who entered traditional employment after graduation have spent the same amount of time gaining industry experience, and are thus able to see their income rise accordingly.

SUSS' Dr Chua noted that while young workers may possess domain knowledge from formal education, they often have not yet been able to apply what they have learnt in real-world settings.

Young gig workers also struggle to build a nest egg that will enable them to look beyond platform work.

Platform workers told CNA TODAY that it is difficult to give up the income such work provides, especially compared to what they might earn elsewhere given their current qualifications.

Taking time off from gig work to upgrade, reskill or go for interviews also translates to lost income.

Financial stability remains precarious for platform workers as illnesses and accidents can abruptly halt their already inconsistent earnings and give rise to potentially hefty medical expenses, said Mr Narasimman Tivasiha Mani, executive director of youth-based non-profit organisation Impart.

This makes it difficult to budget and plan ahead, he added.

EASING THE TRANSITION FOR PLATFORM WORKERS

To support workers and safeguard their interests, a variety of measures have been put in place including the passing of the Platform Workers Bill in 2024.

Under the new legislation that took effect on Jan 1, 2025, increased Central Provident Fund (CPF) contributions are now mandatory for platform workers born on or after Jan 1, 1995. Older workers may opt in if they wish.

Experts hailed this as a step in the right direction, but stressed the need to monitor the impact of the new rules on young workers' cash flows. This is because young riders and drivers may attempt to take on longer hours or unnecessary risks on the road in a bid to maintain their take-home pay levels.

A slew of upskilling initiatives have also been launched, including those by the platforms themselves – such as Grab Academy and Deliveroo Rider Academy – and training providers such as SkillsFuture Singapore.

However, the impact of such initiatives remains uneven, said experts – primarily due to low uptake.

NTU's Dr Ding said: "Riders may not know about (such programmes), be sceptical about the benefits, or find it hard to commit time because of income volatility."

She added that many courses currently available to platform workers are short, stand-alone modules that may be useful for personal development but do not carry "strong signalling power" to employers when compared with full qualifications, industry-recognised certifications or structured apprenticeships.

To this end, experts said additional measures to offer more targeted support to young adults seeking to transition out of platform work could result in better outcomes.

These include stronger, personalised career coaching with guaranteed placements, as well as guidance to match workers' skill sets with the industries they hope to enter.

Other suggestions include clearer transition pathways and "earn-as-you-learn" programmes, greater employer recognition of micro-learning credentials, and better translation of gig experience into formally recognised competencies.

SUSS' Dr Chua said career coaching could help young workers identify the skills they have gained through platform work and the higher-level competencies they need to move into traditional employment.

For such coaching to be effective, she said, it must be paired with guaranteed placements or subsidised training so that workers receive not just advice, but clear and actionable career pathways.

Introducing micro-learning courses that platform workers can take on the go may also help address the skills gap for those motivated to upskill but held back by opportunity costs, Dr Chua noted.

However, such micro-courses must also be formally recognised or endorsed by industry employers in order to be relevant, she added.

Given that upskilling and reskilling programmes often require participants to have predictable free time and a basic financial buffer, platform workers often struggle to participate in these because their work schedules are highly variable and concentrated around demand peaks such as lunchtimes, dinnertimes and weekends, said Dr Ding.

"Even when programmes are subsidised, many (workers) worry about whether – and when – the investment will actually 'pay off', given the challenges of switching sectors and the lack of a clear career pathway," she added.

To tackle this, the government may consider building or funding structured transition pathways, said Dr Ding.

These could include "earn-as-you-learn" apprenticeships and bridging programmes that link training directly to vacancies or guarantee interviews with partner employers for workers who complete certain training modules.

Mr Choo, the tutor, agreed that receiving a training allowance would help offset some of the income losses platform workers sustain when they attend courses – even if it doesn't match one's earnings dollar for dollar.

Ms Azlyiana said that flexibility would make it easier for her to seek out more conventional employment, not just in terms of working hours and training schedules but also increased access to childcare support.

Aside from guidance with matching her skills honed in delivery work to suitable full-time roles, she added that employers being more open to hiring workers with unconventional work histories would also make a significant difference.

HELPING WORKERS MAKE INFORMED CHOICES

Ultimately, re-entering traditional employment after several years in platform work may be more challenging but is not impossible, said NTU's Dr Ding.

Transitions become easier when workers can link their gig experience to the traditional sectors they hope to enter – for instance, moving from delivery riding into operations or customer-support roles in the logistics industry.

Accumulated additional credentials, such as part-time diplomas or professional certificates, can also go a long way towards reassuring potential employers of their relevant skills, she added.

Mr Huang Yiyao, 45, worked full-time as a private-hire driver from 2022 to 2024 after he was laid off from his previous role as a vendor manager at a tech company.

During those two years, he continued applying for full-time roles but was often offered junior positions with starting salaries lower than what he was earning from platform work, which kept him behind the wheel.

The flexibility of driving, however, allowed him to sign up for various reskilling courses, including resume-writing workshops and a three-month, full-time train-and-place data analytics course run by NUS.

He was also able to partially offset the income losses by participating in Grab's Partner Growth Support Scheme, a programme that rewards the platform's riders and drivers with points when they take selected courses at Grab Academy.

These points can then be exchanged for funds in the driver's e-wallet on the Grab Driver Partner app.

These upgrading efforts helped him acquire the skills he needed to eventually move into his current role as a human resource management trainee at a logistics firm.

Beyond these, one other crucial policy intervention is information provision, said NUS' Dr Seah – specifically, ensuring that young people have accurate information about the long-term implications of platform work on their career mobility and trajectories.

"Currently, many young people may be involved in platform work right after school or NS because they have underestimated the longer-term implications on their subsequent labour market outcomes and opportunities.

"These younger workers may believe – incorrectly – that exiting platform work and entering formal work (later on) would be an easy process."

Dr Kelvin Seah of NUS says young people involved in platform work right after school or NS may believe – incorrectly – that exiting platform work and entering formal work later on would be an easy process.

A 40-year-old private-hire driver, who declined to be named, said he has been driving full-time for about six years. He took it up as an interim job after leaving his previous position in sales and operations, hoping to return to traditional employment once things stabilised.

But despite his worries about losing the soft and technical skills he has not used in years, he finds himself unable to transition back to the corporate world as planned.

He now feels anxious about applying and interviewing for full-time jobs, fearing he may not have relevant recent experience to draw on. This, he said, makes him even more inclined to remain in platform work which still enables him to earn more than full-time alternatives available to him.

At the same time, he acknowledges that his prospects in the gig economy have been worsening.

He recalls earning around S$5,000 a month when he first started out, driving eight to 10 hours a day. The same amount of time spent driving now only earns him about S$3,000 to S$4,000 a month, he said – a decline he blames on changing fare structures and an influx of new gig workers in recent years.

He also noted that rising costs such as vehicle rental and petrol prices have been eating further and further into his earnings of late.

NUS' Dr Seah said more awareness about the trade-offs of gig work may encourage more young people to try harder for formal employment rather than defaulting too quickly to highly accessible platform work.

However, the crux of the matter is not painting platform work as either inherently positive or negative, said Mr Shamil.

"People have the freedom to choose the kind of work they want to do. But when they enter gig work, they (should) do so with their eyes open, making informed decisions."