TODAY Youth Survey: Large majority say having a degree is still necessary to succeed in S'pore, expect their children to attain it

(Photo: Nuria Ling/ TODAY)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE — After 23-year-old Gabriel Wong obtained his International Baccalaureate diploma in 2018, he felt it was only natural to pursue a university degree next — he did not seriously consider any other alternative.

“To be blunt, it’s difficult for the average person to be competitive in the modern job search without a university degree,” said the information systems student at Singapore Management University.

After all, he noted, many recruitment advertisements still call for candidates to have at least a Bachelor’s degree or equivalent.

And were he to have children in future, he would expect them to pursue a university degree too, which he feels is the prudent choice, unless they decided to become entrepreneurs or had other passions and goals.

Similarly, 28-year-old Chelsea Teo, who had her first child in July, told TODAY that she believes a university education is necessary for her child’s personal development and that it would build a foundation for future career growth and progression, regardless of the path she chooses to take.

Beyond serving as a safety net to fall back on, the human resource professional, who is a degree-holder herself, said that going through a university education could also teach her daughter to "persevere, be resilient, think critically, and build the confidence needed for (her) future success".

Mr Wong and Ms Teo’s views reflect the sentiments of most other youth respondents in TODAY’s Youth Survey 2023, an annual survey that seeks to give a voice to Singapore's millennials and Gen Zers on societal issues and everyday topics close to their hearts.

This is the third edition of the survey, and it looked at youths’ views on housing, the importance of a university degree, career development, the gap between blue collar and white collar wages and civic participation.

This year's survey, which was conducted in August, polled 1,000 respondents aged between 18 and 35.

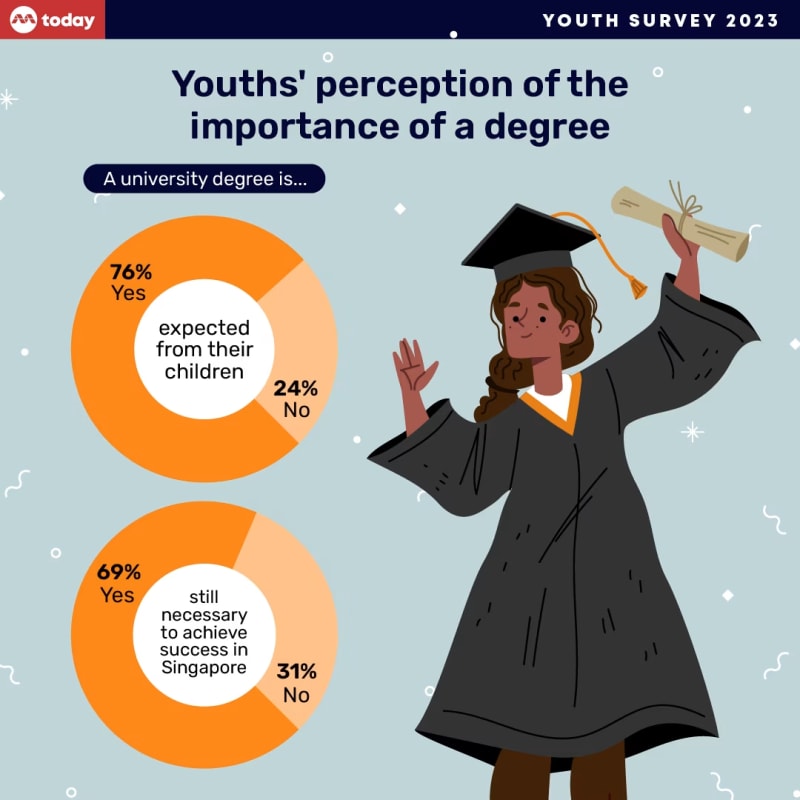

Among those surveyed, 76 per cent said they expect their children or future children to obtain a university degree.

Sixty-nine per cent also said that having a degree is still necessary to achieve success in Singapore.

The Government has spoken extensively about encouraging “multiple pathways of success” and the need for a “broader and more open meritocracy”, while also making changes in the education system to de-emphasise the importance of academic qualifications.

For example, from next year, secondary school streaming will be abolished and replaced with subject-based banding to reduce the stigma often associated with streaming, which is based on grades.

In 2021, the scoring system for the Primary School Leaving Examinations was overhauled to grade students based on their individual performance in subjects, regardless of how their peers have done, to reduce competitiveness and de-emphasise grades.

Earlier this year, Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong called for the professionalising of skilled trades, such as the work done by electricians and plumbers, to assure graduates from the Institute of Technical Education (ITE) and polytechnics that their wage and career prospects would not be too far below their university-going peers.

Yet, that such sentiments — as uncovered in the survey — persist in spite of concrete steps taken by the Government, suggest that much still has to be done to reframe Singaporeans’ perceptions.

Sociologists told TODAY that structural reforms must accompany government messaging, for Singapore to move the needle on this matter.

AN ASPIRATION GAP

The survey also found that youths who are highly educated and more well off were more likely to say that they expect their future children to have degrees too:

- 95 per cent of the youths polled who had a monthly household income of S$20,000 or more agreed they expected their future children to have a university degree, as did

- 92 per cent of those who had a monthly household income of between S$15,000 and S$19,999

- 86 per cent of those who had a degree or higher

- 82 per cent of those who lived in private property

Those who came from humbler backgrounds or did not have degrees themselves were less likely to expect their children to obtain university degrees:

- 68 per cent of those who had a monthly household income of less than S$4,000

- 65 per cent of those who had a secondary-level education or lower

- 57 per cent of those who had a polytechnic diploma or equivalent

There was a similar outcome to the question of whether a degree is still necessary to achieve success in Singapore, with those who were more well off and highly educated more likely to agree:

- 78 per cent of those who had a household income of S$20,000 and above

- 77 per cent of those who had a household income of between S$15,000 and S$19,999

- 73 per cent of those who had a degree or higher

In contrast, 62 per cent of those who had an ITE or A-Levels certification or equivalent and 59 per cent of those who had a polytechnic diploma or equivalent said they agreed that a degree was necessary for success.

The results point to “social reproduction”, wherein the wealthy and well-educated have higher expectations and aspirations of their children, and hence spur them on to achieve more than the children of the less wealthy and educated, said Dr Vincent Chua, an associate professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

“In other words, a class-gap in aspirations exists. In a more equal society, class should have no bearing on aspirations, where the less privileged dream too and are able to see their dreams translate.”

Dr Yang Peidong, an assistant professor at the National Institute of Education whose research interest includes the sociology of education, said: “Some might question: Shouldn’t youth from lower-income families value university education even more, as a way to gain social mobility? While this might sound logical, it’s not quite how it works in reality.”

He noted that higher-income families can more easily afford the cost of university education and are hence more inclined to expect their children to pursue a degree.

On the other hand, it would be harder for lower-income families to afford a university education, which has become increasingly costly, and these families may have to think harder about whether university education was a “worthy investment”, he said.

Dr Yang added that those who pursued a polytechnic education likely realised, through their own experience, that a technical or more practically-oriented education has prepared them well for the job market, and hence considered university education to be less essential.

PAPER QUALIFICATIONS A ‘FOOT IN THE DOOR’

Speaking to TODAY, some youths agreed they were less likely to expect their children to obtain a degree if they could be convinced that an alternative path could still bring them success in life.

Mr Muhammad Muhaimin Zaini, 27, is one such youth. He chose to work full-time to support his family after graduating from Temasek Polytechnic in 2016, and believes the importance of a university education is contingent on one’s chosen career path.

The Building Information Modelling technologist told TODAY that having a degree was not a “make-or-break factor” in his field of work, and added that if one’s career revolved around specific skill sets like BIM or programming, a university degree may “not be as critical”.

For Mr Zaini, who obtained his first diploma in Interior Architecture and Design, an alternative path to university education could look like what he did — enrolling in a subsequent specialist diploma in Building Information Modelling Management at Singapore Polytechnic to deepen his technical skill sets for a career he was passionate about.

As such, his expectations for his child’s education would also depend entirely on their chosen career path in future, he said.

“As technology advances rapidly, the ability to excel in a job will often outshine the possession of a degree. I believe that, over time, employers’ expectations and perspectives will continue to evolve,” said Mr Zaini.

Regardless of their stance on a degree’s necessity, youths across the board said that possessing a paper qualification was ultimately just getting a “foot in the door”.

“I think that in Singapore, while a university degree is often your foot in the door and could enhance opportunities, success isn’t solely tethered to academia,” said Mr Wong, the Singapore Management University student.

He added that some thriving professionals attribute their success more to “specialised skills, networking, and practical experience” rather than formal education.

QUALIFICATIONS AND SKILLS SHOULD COME HAND-IN-HAND

There is indeed a growing emphasis on a “skills-first” hiring approach, which the World Economic Forum defines as stressing a person’s skills and competencies over their degrees, job histories or job titles when attracting, hiring, developing, and redeploying talent.

But this does not mean paper qualifications cease to be important, only that they are now no longer the only thing that matters.

In fact, Dr Chua from NUS said a degree would continue to matter as society continues moving towards a knowledge-based economy and becomes less and less an industrial one.

“The importance of degrees will only grow. True, the comparative advantage of degrees will fall as more people obtain degrees, but this only serves to reinforce the basic necessity of a degree. It has become a non-negotiable.”

Ms Shalynn Ler, Singapore general manager of executive search firm Ethos BeathChapman, added: “From a cultural perspective too, in Asia, while values are shifting slowly to focus on other aspects of success in addition to academic results, most youths themselves would have grown up in an environment where academic results are still tied to success. Hence, it will be hard to totally shift away from this.”

She acknowledged that while Singapore may be moving towards a skills-first approach, the trend remains more prominent among “seasoned professionals with rich achievements”.

In the absence of relevant work experience, fresh graduates would often still have to emphasise their education levels and cover letters to distinguish themselves, she said.

Still, she said this might shift as more millennials become hiring managers themselves and see the value in a skills-first hiring approach.

Acknowledging this, Mr Zaini said: “For fresh graduates, there is undoubtedly a salary difference between degree and non-degree holders. However, with experience, opportunities are based on your skills and achievements rather than qualifications.

“If an organisation values you, a non-degree holder might earn more than a degree holder. Ultimately, work experience speaks for itself, and as you gain experience, qualifications become less significant in the job market.”

TODAY will be going live on Oct 19 and 20 to discuss the findings of the Youth Survey. Tune in to the webinars at https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/today-goes-live-2023-2259246